Why Do Pirates Love Parrots? (15 page)

Read Why Do Pirates Love Parrots? Online

Authors: David Feldman

C

ertain conditions are required for clouds to emerge. Most important, clouds form only in air that is saturated with ice or water. Most areas of the sky are neither moist enough nor cold enough to reach this saturation level, much to the pleasure of suntan lotion marketers. Steve Corfidi, of the National Weather Service, wrote to

Imponderables

emphasizing that clouds are only seen where air is forcibly uplifted and/or otherwise cooled to reach saturation. When air rises, it cools and loses its ability to hold moisture, leading to cloud and droplet formation. On the contrary, when air sinks, it warms, enabling it to hold more moisture, and droplets (and clouds) can evaporate back into invisible water vapor.

And how is this saturation achieved? Corfidi explains:

There are many ways by which air may undergo lifting and/or cooling to form clouds. For example, the cooling of moist air collecting in low spots at night can result in saturation and the development of patches of fog. Differential heating of the ground by the sun (e.g., strong heating over urban rooftops versus columns of rising air, called thermals) [can cause clouds]. If these columns extend high enough, condensation occurs and a cumulus cloud is born.

On an even smaller scale, small areas of upward and downward motion sometimes develop within an existing sheet of clouds. This most commonly occurs when there is shear in the cloud layer (winds which change in direction and/or speed with height) and the layer is thin. The resulting upward and downward motions produce the familiar dappled cloud pattern known as “mackerel sky.”

Major contributors to cloud formation are “condensation nuclei,” sites where water droplets form (clouds are nothing but the formation of millions of tiny water droplets and ice crystals—condensed water in liquid or solid form). Dust, pollutants, sea salts, volcanic ash, and residue from grass and forest fires can all be contributors, according to Boston meteorologist Todd Glickman, known for his weather reporting on WCBS-AM radio in New York. Glickman notes that the formation and dissipation of most clouds is a “very localized event.”

The premise of this Imponderable implies that the sky is a worldwide, fluid whole, but Glickman urges us to think small:

Imagine pouring a quart of red food coloring into the Atlantic Ocean near a New York City beach. The coloring will not spread out and uniformly color the water all the way from Iceland to western Africa to eastern Brazil. Rather, it will stay fairly concentrated in a local area, and be acted upon by waves, thermals, and other matters.

The atmosphere acts similarly; clouds will grow and dissipate in their own little space, independent of what is happening on the other side of the world.

Submitted by Randy K. Laist of Orange, Connecticut.

Club

Soda?

I

n various parts of the world, underground springs produce naturally carbonated water (but only where water has absorbed carbon dioxide under high pressure). Some insist that effervescent spring water aids digestion and helps cure various ills.

An Englishman, Joseph Priestley, who in his spare time accomplished another minor achievement (discovering oxygen), was the first person to artificially create carbonated water. In 1772, Priestley published

Impregnating Water with Fixed Air,

to trumpet his achievement (if you search the Internet, you will find several Web sites devoted to the science and philosophy of this interesting character). Although Priestley shared samples of his discovery with friends, carbonated water only became a commercial product in the early nineteenth century when a Yale chemistry professor, Benjamin Silliman, bottled and sold seltzer water. Seltzer was and is, simply, filtered water with carbon dioxide added.

Silliman may or may not have been preceded by a Swiss chemist, Jacob Schweppe, who like Priestley, at first gave away his handiwork, but unlike the Englishman, eventually started charging. Schweppe’s main contribution to carbonated water technology was perfecting a bottle that would retain the bubbles and allowed for mass distribution. By the mid-nineteenth century, J. Schweppe & Co., the predecessor of today’s soft drink giant Cadbury Schweppes, was a thriving business in Europe.

The word “soda” was associated with many beverages as early as the late eighteenth century, according to Gregg Stengel, of Dr Pepper/Seven Up, Inc., but there are many claimants to the “club.” According to lexicographer Stuart Berg Flexner’s

Listening to America,

the expression “country club” was coined in the United States in 1867. From that point on, the word “club” continued to gain in popularity, conjuring an image of exclusivity, refinement, and panache. Decades hence, everything from “nightclub” to “club sandwiches” was exalted by these associations of class.

At antique bottle collector and author Digger Odell’s Web site, http://www.bottlebooks.com/Carbonated%20Beverages/carbonated_ beverage_trademarks%201890-1919.htm, you can see photographs of soda and carbonated beverage trademarks from 1890 to 1919 that show how “club” had infiltrated soft drink marketing. A 1901 trademark was granted to Country Club Soda Company Corporation, but ironically, club soda was not part of its line of products. One of the most valuable brands of that era was Clicquot Club, which marketed an extremely popular ginger ale—and no club soda.

Gregg Stengel told

Imponderables

that

Schweppes called many of their waters soda. The first reference to “club soda” was when the W.G. Pegram Company sold its beverage firm in South Africa to Schweppes in the 1920s. Pegram had a beverage which was called “club soda,” which added to Schweppes soda, table waters and tonics. It is believed the name came from the many social clubs that were prevalent during that time. These clubs had musical concerts and arranged cricket matches.

Canada stakes its claim in the club soda sweepstakes, too. Many resorts in the Canadian Rockies have naturally carbonated springs, and the expression “club soda” became popular there. In the minds of many North Americans, club soda is associated with Canada Dry, a product that was indeed created in Toronto by pharmacist John J. McLaughlin. At first, he sold carbonated water to soda fountains (which were then almost always found in pharmacies), but in siphon bottles, to be squirted into fruit juices, fruit extracts, and syrups. Further complicating the Canadian “club connection” was the success of Hiram Walker, the first distiller to stop selling in bulk from wooden barrels and brand its product in smaller bottles for individual use. In order to give his product a touch of class, Walker called his product “Club Whiskey.” The success of Club Whiskey set off alarm bells in the U.S. liquor industry and xenophobia in Congress—mandating that Walker call his product “Canadian Club.”

Marie Cavanagh, director of information services at the National Soft Drink Association, wrote

Imponderables

that she was surprised that there is so little information about the origins of club soda. She buys the theory that the soda was used as a mixer in social clubs, but she was unable to verify this information from her organization’s reference books.

While we can’t claim to have a definitive answer, we did stumble onto one label on http://www.bottlebooks.com that gave us pause. Although the trademark was not registered until 1906 (still long before Schweppes sold its first club soda), an Irish company first sold a product called Cantrell & Cochranes Super Carbonated Club Soda in 1877. Is this the first club soda?

Submitted by John Beton of Chicago, Illinois.

S

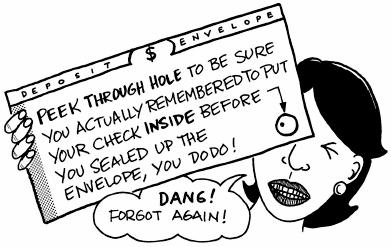

ometimes, a hole is not just a hole. Those openings in ATM envelopes are known as “security holes” and they serve a purpose beyond providing fresh air for your hard-earned cash or paycheck.

In most cases, the party who is being protected by the security holes is the bank that operates the ATM. Customers are known to make mistakes and criminals are known to commit frauds. Joseph Richardson, of Diebold, Incorporated, told

Imponderables:

The holes in the ATM deposit envelope are an attempt by financial institutions to mitigate the risk of consumer error or intentional fraud. All ATM deposits are “subject to verification” of the content of the deposit envelope once it is opened. Without the holes, an empty envelope was only discovered once it was opened and disputes occurred about what happened to the contents. With holes, the ATM deposit handler can see that the envelope is empty and leave it intact, thus mitigating the opportunity for disputes.

Some banks ask us to mark the outside of the envelope, indicating whether we are depositing cash or checks; others provide deposit slips that we slip inside the envelope. Most banks count the money by putting the cash deposits and checks into separate piles. Especially in the early days of ATMs, customers were reluctant to deposit cash, fearing that a random bank clerk would abscond with their money and head directly to the beaches of Cancun.

Fear not—the banks are at least as paranoid as any customers. Standard procedure dictates that ATM coffers are opened in teams, with at least one supervisor and one clerk checking the contents of ATM deposits. The holes allow the employees to see whether cash is included. Even when patrons are asked to specify on the envelope whether cash is being deposited, a surprising number of bank customers, whether unintentionally or not, omit the cash or include less than stated. For obvious reasons, the banks are hardliners about such disputes, especially involving cash—otherwise, they would be sitting ducks for scammers.

The location of the security holes is not random, either. They must provide visual access to the contents of the envelope but stay out of the way, as Richardson explains:

ATMs are designed to print information regarding the transaction on the deposit envelope. This information is often used in balancing the transaction. Holes are placed on the envelope so that they will not interfere with the print line. Thus, the number and position of holes needs to be sufficient to quickly determine whether or not the envelope contains a deposit and still not interfere with the deposit handling module in the ATM.

New ATM technology eliminates the need for any deposit envelope. Checks are imaged and read for processing and bills are counted and validated at the ATM!

Most of the big banks in the United States are experimenting with image readers now. While most bank customers love withdrawing money from ATMs, many are still reluctant to deposit money to a machine, especially cash. Image readers confirm the amount of cash or checks deposited quickly, and the customer agrees to the amount before the money is snarfed by the ATM. The chances of a dispute have been lessened considerably, as the receipt for the transaction will always match the amount of money that the image reader confirms.

Although these new-fangled readers are costly for banks to buy and install, the savings for them are not just in reducing human teller transactions; the biggest savings is in back office operations. With envelope deposits, employees must open the envelopes manually, sort the checks and cash, key in data, run the checks through encoders, and integrate the deposit into the customer’s account balance. With the new machines, the transaction itself can be processed right away. Whether this quicker processing leads to the customer getting credit for the deposit faster, we have our doubts.

Submitted by Crystal Nie of El Cerrito, California. Thanks also to Greg Kligman of Montréal, Quebec.