Why aren’t we Saving the Planet: A Psycholotist’s Perspective (16 page)

Read Why aren’t we Saving the Planet: A Psycholotist’s Perspective Online

Authors: Geoffrey Beattie

Tags: #Behavioral Sciences

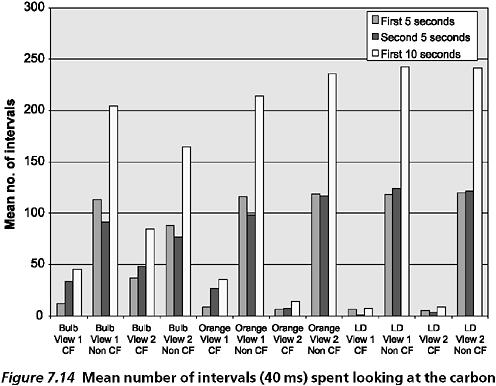

5 seconds (view 1) and in the overall 10-second interval (view 1). However, with the alternative view – view 2 (that is, the front of the product on the left in the photograph) – there were no significant differences. In other words, this array of statistical comparisons revealed a rank ordering in the products in terms of visual attention to the carbon footprint information in the first 10 seconds, with the bulb in first place, the orange juice in second place and the detergent last.

The analysis of the first fixation revealed striking individual differences in terms of where our experimental participants fixated for the first time when they looked at the packaging of certain products. There were also striking individual differences in terms of how long each of these

Figure 7.14

Mean number of intervals (40 ms) spent looking at the carbon footprint (icon plus info) for each of the three products.

first fixations lasted for. Participant 1 (light bulb, view 1) looked first at the wattage information on the light bulb with a fixation of 200 ms, whereas participant 3 (light bulb, view 1) looked first at the EDF label with a much longer opening fixation of 2.5 seconds. Interestingly, participant 7’s first fixation on the light bulb (view 1) was on the carbon footprint icon with an initial fixation of 480 ms. With 10 participants and 6 slides there were 60 initial fixations to consider and out of those, only 4 were on the carbon footprint icon (and none were on the accompanying carbon footprint information). In other words, in less than 7% of all cases did participants fixate immediately on either the carbon footprint icon or the accompanying carbon footprint information when they looked at the packaging of products in which the carbon footprint was clearly labelled.

So what conclusions can we draw from all of this? There is a major argument proposed by many prominent individuals that one way of tackling climate change, and halting the year-on-year increase in greenhouse gas emissions, is to

Table 7.5

Mean number of intervals (40 ms) spent looking at the carbon footprint (icon plus info) for each of two products compared statistically

Seconds | Product view | Product view | Statistical comparisons |

| Light bulb (view 1) | Orange juice (view 1) | |

First 5 | 11.8 | 8.8 | not significant |

Second 5 | 33.7 | 26.8 | not significant |

First 10 | 45.5 | 35.6 | not significant |

| Light bulb (view 2) | Orange juice (view 2) | |

First 5 | 36.9 | 6.4 | significant |

Second 5 | 48.3 | 7.8 | not significant |

First 10 | 85.2 | 14.2 | significant |

| Light bulb (view 1) | Detergent (view 1) | |

First 5 | 11.8 | 6.6 | significant |

Second 5 | 33.7 | 1.0 | significant |

First 10 | 45.5 | 7.6 | significant |

| Light bulb (view 2) | Detergent (view 2) | |

First 5 | 36.9 | 5.2 | significant |

Second 5 | 48.3 | 3.6 | significant |

First 10 | 85.2 | 8.8 | significant |

| Orange juice (view 1) | Detergent (view 1) | |

First 5 | 8.8 | 6.6 | not significant |

Second 5 | 26.8 | 1.0 | significant |

First 10 | 35.6 | 7.6 | significant |

| Orange juice (view 2) | Detergent (view 2) | |

First 5 | 6.4 | 5.2 | not significant |

Second 5 | 7.8 | 3.6 | not significant |

First 10 | 14.2 | 8.8 | not significant |

empower consumers to make informed adjustments to their patterns of consumption, by providing them with relevant and accurate information about carbon footprint. The fact that many people do seem to have a strong positive implicit attitude to low carbon footprint products lends some credence to this general view. People would seem to be (already) primed to change their behaviour. A number

of retailers (including Tesco in the UK) are now selling products with carbon footprint information clearly marked on their own-brand products to allow this empowering process to commence.

But the interesting psychological question is to what extent the carbon footprint information (usually consisting of an icon plus accompanying textual material) successfully directs the consumers’ visual attention to itself, in competition with all the other information that appears on the packaging or on the products themselves. Detailed analyses of the recording of each participant’s pattern of looking (each 40 ms frame was manually coded) during two 5-second periods of regard revealed that with certain products significant amounts of attention were directed at the carbon footprint and it did occur within the first few seconds. In our research, which compared three different products, most visual attention was directed at the carbon footprint of a low-energy light bulb compared with the carbon footprint of a carton of orange juice or a container of detergent. Least visual attention was directed at the carbon footprint of the detergent. In the case of the light bulb, attention was directed within the first 5 seconds at the carbon footprint icon, but attention only moved to the accompanying textual material in the second 5-second period (with only minimal attention in the first 5 to this textual material). It seemed to take much longer for participants to attend to the basic carbon footprint icon in the case of the orange juice (only really appearing in the second 5-second interval), and in the case of this product they hardly attended to the accompanying information at all. In the case of the detergent there was minimal visual attention to any aspect of the carbon footprint.

Bowman, Su, Wyble and Barnard (2009) recently wrote that ‘Humans have an impressive capacity to determine what is salient in their environment and direct attention in a timely fashion to such items.’ Carbon labelling on products, which some see as a major part of the solution to the issue of climate change, should surely be a salient part of all of our everyday lives, but it seems that it is only the carbon footprint of

certain

products that is really salient (at least within

the critical 5-second time frame of everyday supermarket shopping). Our research also found that the carbon label (the carbon footprint icon plus the accompanying information) was the focus of the

first

fixation of our participants in only about 7% of all cases (and only 10% of the first fixations even in the case of the low-energy light bulb). In other words, the carbon label is not where participants look first. From a psychological point of view the only way that carbon labelling will ultimately work is if the information is designed in such a way that it does become the primary focus of visual attention in the first few seconds. At the moment this appears to occur only with certain products, which we already associate with being ‘green’. How we redesign products to make this information stand out more thus becomes a critical issue in the fight against climate change, as does the issue of how we go about making carbon footprint information more emotionally salient to people generally. The reason for this is that we know that emotional valence, and our values more generally, affect our perceptions of the world (Bruner and Goodman 1947). They even affect the moment-to-moment unconscious eye movements that are the crucial building blocks of this process of perception (and also, of course, the subject of our own research).

The overall implication is that if we are to combat climate change by providing consumers with carbon footprint information, then we will need to consider much more carefully how to make this carbon footprint information significantly more salient, because if the carbon label is not ‘seen’ in the right time frame, then it simply cannot be effective. This process will involve not just changing the packaging of products (essentially a design issue, but guided by psychologists who understand the limits of time-dependent cognitive processing) but also (and somewhat more dauntingly) it will involve changing certain aspects of the fundamental psychology of consumers (and not just their implicit attitudes, which already seem positive), because salience (as we all know) really is in the eyes of the beholder. So until we change crucial aspects of the psychology of the beholder, none of this activity on carbon labelling will really work, despite the very best of intentions.

Notes on habits

Eden reclaimed

I was slowly walking back to my hotel room, stepping carefully around snails with large, almost comical heads, and brightly coloured shells. They were the size of small rotund sparrows. It was 1.30 a.m., the end of another day in paradise. I was staying in a beautiful hotel with manicured verdant lawns that swept down to the white sand and clear warm waters of the Indian Ocean. It was now January and I was attending a sustainability conference in Mauritius to present my new research (of course, I saw and

felt

the irony of this).

I had spent the day in various plenary sessions listening to the latest views on environmental sustainability. What was nice about the conference was that it had a type of session called ‘garden conversations’ which were unstructured 60-minute sessions that allowed delegates to meet the plenary speakers and talk with them informally about any emerging issues and, in addition, there were ‘talking circles’ which, according to the organisers, were ‘meetings of minds, often around points of difficulty. They are common in indigenous cultures. The inherent tension of these meetings is balanced by protocols of listening and respect for varied viewpoints. From this, rather than criticism and confrontation, productive possibilities may emerge.’ I had presented my work on the implicit attitudes to carbon footprints and the response was very favourable, many productive possibilities emerged, and I discovered that few researchers interested in sustainability seemed to have thought about this issue before but I could see that many were thinking about it now.

I had chosen a hotel close enough to where the conference was being held just outside Port Louis, in Pointe aux Sables, but really miles apart from the chaos and patchy squalor of that town. I was guided to my room by the sound of the crapaud, the Creole name for the little frogs crying out for a mate in the ponds dotted around the hotel. These were man-made with slate waterfalls, with the water emerging out of the mouths of golden lions, and goldfish swimming under the gentle sparkling falls, but the tropical nature of the island had invaded the interconnected ponds to give them new life; the whole thing pulsated like a membrane. The croaks sounded like the raspy death rattle of a human being, that terrible Cheyne-Stoking sound and rhythm, but with the opposite emotional significance. This noise was all about life and the celebration of libido rather than the celebration that thanatos had finally neared the end of its fateful journey. I timed the interval between the croaks – almost exactly one per second. The whole hotel was pulsating with this incessant noise that seemed to be getting louder. The volume bore no relation to the tiny creatures from which the noise comes. I picked one up to examine it, and it sat quietly in my hand before I released back into the lush pond life.