Whole (30 page)

Authors: T. Colin Campbell

What I’m describing here isn’t a vast, evil conspiracy designed to keep the truth of the plant-based diet from you. Many of the players I’ve criticized truly believe their own PR. Lots of cattle ranchers, dairy farmers, and high-fructose corn syrup manufacturers think they’re providing high-quality calories to a hungry world. Many scientists are just as confused as the general population about the big picture of nutrition and human health. Many journalists report the results of each reductionist study under the honest misconception that they’re describing a comprehensive reality rather than a thin, misleading, out-of-context slice. And many government officials, while privately acknowledging the immense benefits of a plant-based diet, think that promoting such an idea would be counterproductive to their political futures in the face of so much deep-pocketed industry opposition.

The problem is not that humans are broken or evil. It’s that the system is broken. I have spent my entire career in academia and professional research and, like most of my colleagues, I take pride in my institution’s gentility, objectivity, and democratic tradition. Indeed, I believed that I experienced these virtues on many occasions. But that was before I realized I was living in a cocoon, unaware of the subtle way in which financial interests inform every part of the scientific process and beyond.

The thing about systems is that they’re resilient. I’ve learned that the hard way, after spending years sharing the best scientific information with policy makers, businesspeople, and consumers and still not having much of an impact on the entire system. You can tweak all the details—you can correct the science all you want—but if the goal isn’t changed, the system will continue to produce the same outcomes it always has. The logical goal of a health-care system would be to deliver health. That’s the stated goal of ours, certainly. But that’s not its actual goal. To discover that goal, as with any other system, we have to observe what it does, not what it claims to do.

If the goal of our health-care system were health, then it would operate in a way that promotes health. It might look clumsy, sloppy, and slow, but the connections built into that system would favor methods and technologies and interventions that move us all inexorably in the direction of good health throughout our lives. Obviously, that’s not the case. The goal of our health system is not health; it’s profit for a few industries at the expense of the public good.

That’s right—profit is the goal at the center of our health-care system, and that skews everything.

When I say “health-care system” here, I mean more than just doctors, nurses, hospitals, drugs, and surgical apparatus. I mean everything in our society that affects our health, from our agricultural policies, to school lunch programs, to pollution laws, to public education about nutrition, to funding priorities for scientific research, to seat belt enforcement, and so on. This may sound unimaginably complex and hard to manage and

restructure, and on a piecemeal basis it is. But let’s imagine a hypothetical system in which the primary goal is better public health. In such a system, all these elements and policies would naturally tend to produce better health outcomes.

Since my training is in nutritional biochemistry, I often think of the world in terms of nutrient narratives. And the nutrient around which any healthy modern society is organized is information—in this case, information about health, a key product of science that individuals, governments, nonprofits, corporations, and the media consume.

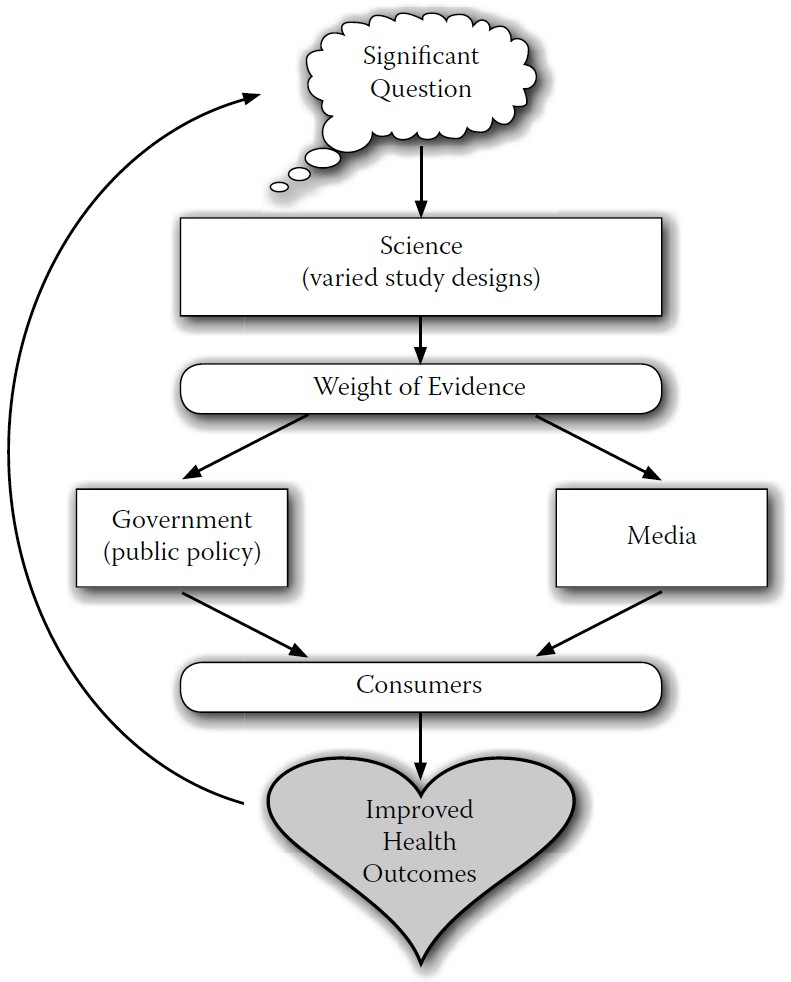

Figure 13-1

is a simplified diagram of how the nutrient information moves through the health-care system.

In an ideal society, the “information cycle” is driven by the goal of empowering people at all levels of society to enjoy healthy lives. That goal would drive the main input of the information cycle, questions that are significant to public health and worthy of research. Scientists would tackle these questions with great curiosity and enthusiasm, collaborating and competing to come up with the most creative, powerful, and valid study designs. Many different studies would be carried out, from the extremely reductionist to the extremely wholistic, which would generate more questions and some controversies. Eventually, a “weight of evidence” would accumulate, consisting of a model that would be tested by its ability to predict future health outcomes. It would not be “The Truth”—science never is—but it would be as close to it as a group of humans could get at that point.

This weight of evidence would then cycle into the rest of society. The media, both professional trade journals and public media organizations such as newspapers, would report it to the people, who would incorporate it into their individual lifestyle choices. Government would create public policy, based on the weight of evidence, designed to promote the general welfare. These two would be the chief sources of public health information. Industry’s role would be to create health-related goods and services based on this evidence, since those things that work best tend to sell best. Businesses would compete to innovate and market new products and services that would better serve public health, based on the evidence. And professional and fundraising organizations would base their philanthropy and marketing on promoting and leveraging the weight of evidence to serve their communities. The result would be improved health outcomes,

which would then lead to the next set of significant questions by showing where health research still needs to be done, in a continuous and never-ending quest for the best health possible.

FIGURE 13-1.

An ideal hypothetical health-care system

It would be nice if our world actually resembled this diagram. But unfortunately, this idealized picture of a society whose goal is better health for its members is a very far cry from the way our system really functions.

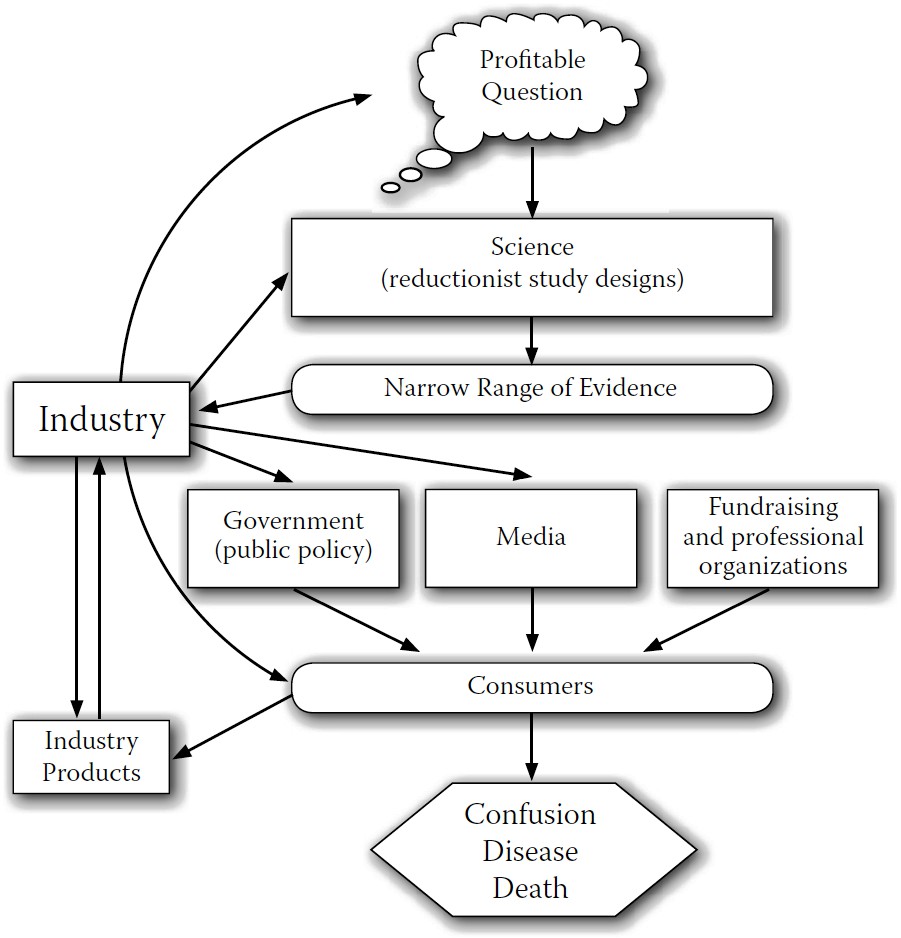

Let’s take a look at reality—at the way the nutrient “information” actually moves through the health-care system, as in

Figure 13-2

. It’s not in service of producing greater health outcomes, but instead in service of profit.

FIGURE 13-2.

Our actual health-care system

When the goal of the information cycle becomes profit rather than health, everything about it becomes distorted. Science, the producer of information from the raw materials of curiosity and funding, creates a monoculture of reductionist research that serves profit, not health. The

output of this research, a narrow range of evidence that precludes wholistic, simple, and powerful solutions, is then turned into myriad temporary and partial solutions that ultimately make things worse. Just as a diet of processed, nutritionally barren food cannot be metabolized for healthy functioning, a diet of processed, wisdom-barren information cannot be metabolized into wise, compassionate, or effective social policy.

Here’s how the profit-distorted information cycle works. At the very top, the questions that are asked have more to do with the potential for profit than breakthroughs in human health. Why bother to think about something when you won’t get the funding to pursue your research? Why build a career on questions that no one will pay for you to investigate? So already the system is excluding questions about how to get more people to eat healthy food, in favor of questions about how to make pills and potions that can be patented and sold at high margins.

These questions comprise what we currently call “science.” All the labs and apparatus and test tubes and white coats are just a means to an end: answers to the questions science is called upon to answer. In contrast to a healthy information cycle, however, science in this case does not investigate the questions with the full range of study methodology available to it. Rather, it limits itself to highly reductionist experimental research designs, which are deemed the only appropriate means of gathering evidence. Not so coincidentally, those are the ones most suited to drug testing, and least suited to complex biology and behavior change. Of course, this systemic limitation produces a very narrow range of evidence, which is then reported and marketed as “the truth,” as opposed to what it really is: a very narrow sliver of experience reflecting an even narrower set of questions posed by people with a hidden agenda. This evidence has two main audiences: the media (owned by industry and/ or funded by industry advertising) and those in government and private think tanks who determine the public health implications of the evidence and recommend policy to make use of it. But the way these two audiences receive and use this evidence is heavily mediated by industry.

Industry uses that narrow range of evidence—or at least what of that evidence the public seems to be responding to—to create new products (including goods and services) and to lobby the government to declare those products “the standard of care.” Procedures and pills so labeled are all but forced upon doctors and hospitals, who fear lawsuits should they deviate

from these treatments. Industry feeds press releases to a largely uncritical media emphasizing only the evidence that supports use of their products. And industry further distorts the evidence by spinning it to the public in the form of advertising, where the occasional benefits are hyped and the considerable side effects are shown in small print or quickly mumbled.

The evidence ends up filtered and distorted, and presented as broader and more meaningful than it is. Any information that contradicts expected narratives is downplayed or doubted. Intentionally or not, this makes it easier for industry to sell more things to us, be they drugs, procedures, nutraceuticals, supplements, expensive running shoe inserts, or diets in a bottle. The health advice we hear are all messages like, “You need dairy to get enough calcium so you don’t get osteoporosis,” and “If you have high cholesterol, you need to take statin drugs.”

With this information, advocacy groups—professional interest groups and fundraising organizations—galvanize public support and collect and contribute money to the activities of science. Because of the limitations of the science they rely on, their donations go to those who seek magic-bullet cures for their diseases of interest. Advocacy groups also influence public policy through PR and lobbying; what politician wants to be branded a “friend of cancer” by not going along with the wishes of the American Cancer Society?

What all this means is that, in the current system, we don’t have free choices; we have constrained choices. We’re just deciding between equally ineffective magic bullet “cures” that don’t work. We buy what is sold to us, enlist in the never-ending crusades against bad diseases, follow mainstream health advice (because to ignore it seems foolish and risky), and donate time, money, and energy to our favorite anti-disease society. All this in the name of achieving better health for ourselves and others, when all it produces is an endless cycle of ever greater confusion, disease, and untimely death while stuffing the wallets of those who control and manage this system. And when you look closely, you’ll see that we the consumers, by unquestioningly buying the products created by a profit-obsessed industry, are funding the whole mess. That’s why one of the most important things any of us can do is improve our own diet and health; we can “vote with our dollars” against this system by opting out. The less we buy, the less money industry can deploy to distort scientific research and government policy.

I need to emphasize that these negative outcomes are not the goal of the current system. They’re simply an unavoidable side effect of the primary goal: ever-increasing profits for the several industries whose activities constitute and maintain the system. As I said, this isn’t a story of nefarious individuals’ intentions; to the contrary, most of the people contributing to the current mess truly believe they’re doing good. They’re waging the war on cancer. They’re uncovering secrets of our genes. They’re putting what are presumably much-needed nutrients in pills and foods. They’re producing breakthroughs in surgical techniques. They’re lowering the cost of calories for the poor. They’re producing animal protein more efficiently. They’re reporting new findings to a public hungry for advice about how to be thinner and healthier. And yet these wonderful intentions end up in the service of more profit and more disease.