Who Owns the Future? (7 page)

Read Who Owns the Future? Online

Authors: Jaron Lanier

Tags: #Future Studies, #Social Science, #Computers, #General, #E-Commerce, #Internet, #Business & Economics

A winner-take-all distribution.

The distributions of outcomes in fashionable, digitally networked, hyperefficient markets tend to be winner-take-all. It’s true for tech startups, for instance; only a few succeed, but those that do can amass stupendous fortunes. It’s also true for new kinds of individual success stories in the online world, as when someone actually earns serious money from a smartphone app or a video uploaded to YouTube; only a tiny number do well, while the multitudes dream but fail.

The other familiar distribution is the bell curve. That means there is a bulge of average people and two tails of exceptional people, one high and one low. Bell curves arise from most measurements of people, because that’s how statistics works. This will be true even if the measurement is somewhat contrived or suspect. There isn’t really a single type of intelligence, for instance, yet we take intelligence tests, and indeed the results form a bell curve distribution.

A bell curve distribution.

In an economy with a strong middle class, the distribution of economic outcomes for people might approach a bell curve, like the distribution of any measured quality like intelligence. Unfortunately, the new digital economy, like older feudal or robber baron economies, is thus far generating outcomes that resemble a “star system” more often than a bell curve.

What makes one distribution appear instead of the other?

Tweaks to Network Design Can Change Distributions of Outcomes

Later on I’ll present a preliminary proposal for how to organize networks to organically give rise to more bell curve distributions of outcomes, instead of winner-take-all distributions. We don’t know as much as I believe we one day will about the implications of specific network designs, but we already know enough to improve what we do.

Winner-take-all distributions come about when there is a global sorting of people within a single framework. Indeed, a bell curve distribution of a quality like intelligence will generate a winner-take-all outcome if intelligence, whatever that means according to a single test, is the only criterion for success in a contest.

Is there anything wrong with winner-take-all outcomes? Don’t they just promote the best of everything for the benefit of everyone? There are many cases where winner-take-all contests are beneficial. Certainly it’s beneficial to the sciences to have special prizes like the Nobel Prize. But broader forms of reward like academic tenure and research grants are vastly more beneficial.

Alas, winner-take-all patterns are becoming more common in other parts of our society. The United States, for instance, has famously endured a weakening of the middle class and an extreme rise in income inequality in the network age. The silicon age has been a new gilded age, but that need not and ought not continue to be so.

Winner-take-all contests should function as the treats in an economy, the cherries on top. To rely on them fundamentally is a mistake—not just a pragmatic or ethical mistake, but also a mathematical one.

A star system is just a way of packaging a bell curve. It presents the same information using a different design principle. When used foolishly or excessively, winner-take-all star systems amplify errors and make outcomes less meaningful.

Distributions can only be based on measurements, but as in the case of measuring intelligence, the nature of measurement is often complicated and troubled by ambiguities. Consider the problem of noise, or what is known as luck in human affairs. Since the rise of the new digital economy, around the turn of the century, there has been a distinct heightening of obsessions with contests like

American Idol,

or other rituals in which an anointed individual will suddenly become rich and famous. When it comes to winner-take-all contests, onlookers are inevitably fascinated by the role of luck. Yes, the winner of a singing contest is good enough to be the winner, but even the slightest flickering of fate might have changed circumstances to make someone else the winner. Maybe a different shade of makeup would have turned the tables.

And yet the rewards of winning and losing are vastly different. While some critics might have aesthetic or ethical objections to winner-take-all outcomes, a mathematical problem with them is that noise is amplified. Therefore, if a societal system depends too much on winner-take-all contests, then the acuity of that system will suffer. It will become less reality-based.

When a bell curve distribution is appreciated as a bell curve instead of as a winner-take-all distribution, then noise, luck, and conceptual ambiguity aren’t amplified. It makes statistical sense to talk about average intelligence or high intelligence, but not to identify the single most intelligent person.

Letting Bell Curves Be Bell Curves

Star systems in a society come about because of a paucity of influential sorting processes. If there are only five contests for stars, and only room for five of each kind of star, then there can only be twenty-five stars total.

In a star system, the top players are rewarded tremendously, while

almost everyone else—facing in our era an ever-larger, more global body of competitive peers—is driven toward poverty (because of competition or perhaps automation).

To get a bell curve of outcomes there must be an unbounded variety of paths, or sorting processes, that can lead to success. That is to say there must be many ways to be a star.

In schoolbook economics, a particular person might enjoy a commercial advantage because of being in a particular place or having special access to some valuable information. In antenimbosian

*

days, a local baker could deliver fresh bread more readily than a distant bread factory, even if the factory bread was cheaper, and a local banker could discern who was likely to repay a loan better than a distant analyst could. Each person who found success in a market economy was a local star.

*

“Before the cloud.”

Digital networks have thus far been mostly applied to

reduce

such benefits of locality, and that trend will lead to economic implosion if it isn’t altered. The reasons why will be explored in later chapters, but for now, consider a scenario that could easily unfold in this century: If a robot can someday construct or print out another robot at almost no cost, and

that

robot can bake fresh bread right in your kitchen, or at the beach, then both the old bread factory

and

the local baker will experience the same reduction of routes to success as the recording musician already has. Robotic bread recipes would be shared over the ’net just like music files are today. The economic beneficiary would own some distant large computer that spied on everyone who ate bread in order to route advertisements or credit to them. Bread eaters would get bargains, it’s true, but those would be more than canceled out by reduced prospects.

Star Systems Starve Themselves; Bell Curves Renew Themselves

The fatal conundrum of a hyperefficient market optimized to yield star-system results is that it will not create enough of a middle class

to support a real market dynamic. A market economy cannot thrive absent the well-being of average people, even in a gilded age. Gilding cannot float. It must reside on a substrate. Factories must have multitudes of customers. Banks must have multitudes of reliable borrowers.

Even if factories and banks are made obsolete—and this is likely to happen in this century—the underlying principle will still apply. It is an eternal truth, not an artifact of the digital age.

The prominence of middle classes in the last century actually made the rich richer than would have a quest to concentrate wealth absolutely. Broad economic expansion is more lucrative than the winner taking all. Some of the very rich occasionally express doubts, but even from the most elite perspective, widespread affluence is best nurtured, rather than sapped into oblivion. Henry Ford, for instance, made a point of pricing his earliest mass-produced cars so that his own factory workers could afford to buy them. It is that balance that creates economic growth, and thus opportunity for more wealth.

Even the ultrarich are best served by a bell curve distribution of wealth in a society with a healthy middle class.

An Artificial Bell Curve Made of Levees

Before digital networks, eras of technological development often favored winner-take-all results. Railroads enthroned railroad barons; oil fields, oil barons. Digital networks, however, do not intrinsically need to repeat this pattern.

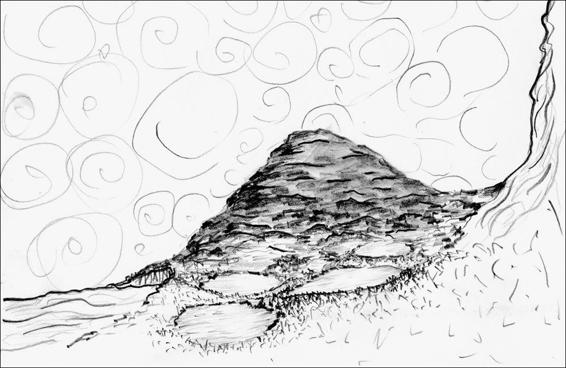

Unfortunately, in many previous economic and technical revolutions, there was no alternative but to accept situations that tended to yield star-system results. Capital in these situations resisted rising up into a middle class mountain, just as would any fluid. To combat the degradations of star systems, an ad hoc set of “levees” awkwardly arose over time to compensate for the madness of fluid mechanics and protect the middle class.

Levees are broad dams of modest altitude intended to hold back the natural flow of fluid to protect something precious. A mountain

of them rising in the middle of the economy might be visualized as a mountain of rice paddies, like the ones found in parts of Southeast Asia. Such a mountain rising in the sea of the economy creates a prosperous island in the tempest of capital.

An ad hoc mountain of rice-paddy-like levees raises a middle class out of the flow of capital that would otherwise tend toward the extremes of a long tail of poverty (the ocean to the left) and an elite peak of wealth (the waterfall/geyser in the upper right corner). Democracy depends on the mountain being able to outspend the geyser. Sketch by author.

Middle-class levees came in many forms. Most developed countries opted to emphasize government-based levees, though the ability to pay for social safety nets is now strained in most parts of the developed world by austerity measures taken to alleviate the financial crisis that began in 2008. Some levees were pseudo-governmental. In the 20th century, an American form of levee creation leveraged tax policy to encourage middle-class investment in homes and at-the-time conservative market positions, like individual retirement accounts.

There were also hard-won levees specific to avocations: academic tenure, union membership, taxi medallion ownership, cosmetology licenses, copyrights, patents, and many more. Industries also arose to sell middle-class levees, like insurance.

None of these were perfect. None sufficed in isolation. A successful middle-class life typically relied on more than one form of levee.

And yet without these exceptions to the torrential rule of the open flow of capital, capitalism could not have thrived.

The Senseless Ideal of a Perfectly Pure Market

Something obvious needs to be pointed out because of the historical moment in which this book is being written. It will probably read as a silly diversion to future readers during saner times. (I am ever the optimist!)

There is shrill, shattering, global debate that pits government against markets, or politics against money. In Europe, should financial considerations from the point of view of German lenders trump political considerations from Greek borrowers? In the United States, a huge wave of so-called populist ideology declares that “government is the problem” and markets are the answer.

To all this I say: I am a technologist and neither position makes sense to me. Technologies are never perfect. They always need tweaks.

You might, for example, want to design a tablet to be pristine and platonic, without any physical buttons, but only a touchscreen. Wouldn’t that be more perfect and true to the ideal? But you can’t ever quite do it. Some extra physical buttons, to turn the thing on, for instance, turn out to be indispensable. Being an absolutist is a certain way to become a failed technologist.

Markets are an information technology. A technology is useless if it can’t be tweaked. If market technology can’t be fully automatic and needs some “buttons,” then there’s no use in trying to pretend otherwise. You don’t stay attached to poorly performing quests for perfection. You fix bugs.