Who Made Stevie Crye? (10 page)

Read Who Made Stevie Crye? Online

Authors: Michael Bishop

Tags: #Fiction, #science fiction, #General

XX

“

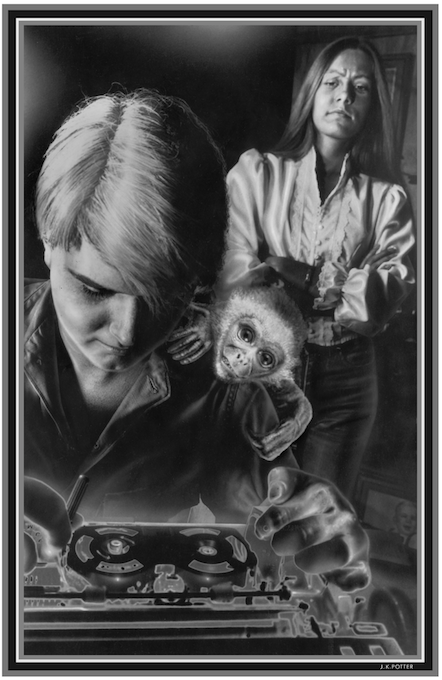

This is a writer’s room

,” Seaton told ’Crets, upstairs. The monkey was riding his shoulder. “That’s her desk . . .and her typewriter.” The study did not appear to impress the animal. “I’ve never seen walls this color. What do you call it?”

“Burgundy,” Stevie said.

“It’s dark. It’s a really dark color.”

“It’s supposed to make me thoughtful and creative. Same with the curtains and the Oriental rug.”

“I like it. It’s kind of Edgar Allan Poe-ish. I mean, you could put a raven up there on one of your bookcases.”

“For want of a bust of Pallas?”

“I can see you going deep into yourself sitting here, digging down into your mind. A good room for imagining stuff in.”

“Sort of like a prison cell.”

“Oh, no, Mrs. Crye. It’s small, but you’re free here. You’re a lot freer than somebody fixing typewriters in a big repair room.”

“I’m chained to my desk. I’m chained to that typewriter the way an organ-grinder monkey is chained to its hurdy-gurdy.” (’Crets shot Stevie a look. He knew the word

monkey

.) “I’ve got just enough slack to go around the circle of my customers with my tin cup stretched out. That’s how free I am, Seaton. Your job’s the equal of mine. It may even be better. You get weekends off. I feel guilty when I’m not using them to fill up that tin cup.”

“Well, I’ll do some work right now.” He took a tiny screwdriver from his fatigue pocket. “It’s Saturday, Mrs. Crye, but I’ll do some work.”

With ’Crets draped around his neck Seaton bent over the PDE Exceleriter 79 and fiddled with the cables beneath the ribbon carrier. Then he popped off the entire hood and, like a surgeon, peered into the cavity of levers, wheels, and cams composing the machine’s gleaming viscera. Stevie stood behind him and watched him work. What was he doing? Sabotaging the machine further or righting the problem that had enabled it to work by itself?

“Seaton?”

“Ma’am.”

“You did something to my Exceleriter the other day that has me very upset. I think you should know that. You said you were giving it a special twist, and that little twist has turned me upside-down. My best friend thinks I’ve flipped my wig, Seaton, and it’s all I can do to keep from taking out my frustration and fear on the kids. This morning I boiled over and spilled about three gallons of frustration and fear right into their laps. It’s the typewriter. The typewriter’s holding me hostage.”

“You know how kids are,” Seaton replied without turning around. “You probably had to bring them up short. Just like you did me and ’Crets downstairs. I deserved that, Mrs. Crye, I really did. Besides, kids’re really flexible, they bounce right back from disappointments.”

“That’s not what I’m talking about, Seaton. Whatever you did to my typewriter Wednesday—supposedly to fix it—is fixing me instead. I think you know what I’m talking about. I’ve been keeping up a semiresolute front since my visit to Dr. Elsa yesterday morning, but I’m on the verge of disintegrating. Is that what you

wanted

to happen?”

Seaton’s fingers ceased their exploratory surgery on the machine. He unbent his back and faced her. For only the second time in their unconventional relationship he purposely met her eyes. The capuchin scrambled about so that the tip of his white-bearded chin was resting on Seaton’s head. From this precarious perch, the monkey added his unyielding stare to the man’s.

“You don’t look like you’re disintegrating, Mrs. Crye. You look just fine. Inside, I mean. Down deep.”

“You’ve got X-ray eyes that let you see inside a person?” Stevie regretted this question. It heightened her uneasiness about Seaton by imputing a dreadful power to him. By sheer dint of will she kept her eyes locked on his and ignored those of the impudent monkey.

“Clinac-18 eyes,” he said, expressionless.

“That’s not an X-ray machine. It’s a beam accelerator. What’re you trying to imply?”

Seaton glanced aside, letting his gaze drift over the pattern in the Oriental rug where she was standing. “You mentioned it in your

Ledger

article. The Clinac 18. It has a beam that goes deep and disintegrates tumors. I was just . . . well, you know, making a comparison. What do writers call them, those fancy comparisons where you say something is something else?”

“Metaphors.”

“That’s right. You said ‘disintegrating’ and then you said ‘X-ray eyes,’ and I just thought of what you’d written in that cancer article, is all. I was doing a metaphor, Mrs. Crye. I probably didn’t do it right, though, because that stuff was always hard for me. That’s why I’ll never be a writer even though I’ve got stories in my head—spooky stuff,

really

scary stuff—that I wish I could get out. I really envy writers.”

“You made my typewriter write by itself, Seaton. Is that some part of

you

operating the machine?”

“What did I do, Mrs. Crye?” His brow furrowed.

“You made the damned Exceleriter write by itself. It types out copy in the middle of the night when I’m not sitting in front of it to do the typing. I think that’s you, Seaton. I think that’s some part of you.”

Swiveling ’Crets so that the monkey no longer stared at her, Seaton looked back over his shoulder at the typewriter. Then he revolved back toward Stevie, let his gaze drift to the Dearborn space heater, and held almost breathlessly still while ’Crets shinnied down his arm to his hip. Seaton’s brow had not yet unwrinkled. If he was acting, he was extraordinarily good at suggesting an unstable mixture of confusion and embarrassment.

“Ma’am?”

“You know what I’m talking about.”

“I don’t think it was any part of

me

, Mrs. Crye. This is the first time I’ve ever been in your house.”

“You had to get inside my house, didn’t you? You had to get upstairs here to see what the place looked like. To measure the impact of your skullduggery. That’s what all this is about, isn’t it?”

Maybe he was human after all. His pudgy schoolboy cheeks reddened a little, and when he responded to these charges, his voice cracked: “I wanted . . . I wanted to fix the

t

.” Had his face flushed from discovered guilt or a charitable embarrassment on her behalf? Stevie could not tell. She clenched her fists at her shoulders and abstractedly tapped her knuckles against her collarbones.

“Then why don’t you go ahead and fix the lousy

t

?”

“I was doing that, Mrs. Crye. I’ll finish the job right now.”

The sun was shining brightly outside, a stunning February day, but her study was chilly. To give her distraught hands something to do, Stevie dug a small box of matches out of her cardigan’s only pocket and lit the space heater. Then she stood there warming her hands behind her and watching Seaton Benecke work. New deviltry or a mechanical exorcism? Stevie convinced herself that she did not care. She just wanted him to complete the job and remove himself and his obnoxious companion from the house. The

t

he was trying to fix stood for

tactic

. Maybe it had succeeded, this tactic, but as soon as he was gone she would win the larger war by putting him out of her mind and never allowing him to darken her threshold again.

“I think that’s got it, Mrs. Crye.” He pressed the metal cover back into place, rolled in a sheet of paper, and pounded out a string of words including

tactic

,

temperature

,

ticket

,

toothpaste

,

turtle

, and

teeter-totter

. “Yes, ma’am, it’s okay now. It’s even better than it was before. It ought to suit you to a

T

.” This last was Seaton’s idea of a joke—another feeble Benecke joke. He gave her a tentative smile, turned back to her (reputedly tractable) machine, and tapped out a final tympanic tattoo, the word

typewriter

.

“Very good, Seaton. You’ve proved your point. Now it’s time for you to leave. I’ve got to check the kids.”

“It’s going to work even better than before, Mrs. Crye.”

“Is it?”

“Yes, ma’am. No matter how well they’re working when I get ’em, I always try to improve on that. It’s what I do. Just like you try to improve on the last article or story you did.”

Stevie refused to encourage Seaton with further comment. She opened the study door and watched tight-lipped and imperceptibly trembling as he pocketed his tiny screwdriver, wiped his hands on his jacket, and searched for any leftover tools or typewriter parts. Although the cold air from the corridor swept past Stevie’s ankles, she kept the study door open to indicate that their interview—their entire association—was over. The sooner he was down the stairs and out on the highway home the sooner the ice in her bone marrow would melt, restoring her to a healthy human warmth.

Disconcertingly ’Crets leapt from Seaton’s hip to the Oriental rug, dashed past Stevie on all fours, and cornered like a miniature stockcar heading into . . . the master bedroom. Stevie was too startled to shout at the monkey. She and Seaton exchanged an ambiguous glance, then bumped shoulders pushing through the doorway in pursuit of the capuchin. At the threshold to her own room she saw ’Crets clambering across the quilted bedspread she had made when Ted, Jr., was a toddler and Marella not yet even the germ of a connubial ambition. The beast had claws. He would ruin this would-be heirloom. Now, in fact, he was leaping from the center of the quilt to the Ethan Allen headboard. His antics—his unthinking tiny-primate presumption—infuriated Stevie.

“I thought he didn’t like the cold,” she accused. “This is the coldest room upstairs because I always keep my shades drawn and the curtains closed. What’s he doing in here, Seaton?”

“You ever read those

Curious George

books to your kids when they were little? ’Crets is curious like that monkey in those children’s books. He can stand the cold for a while, Mrs. Crye. The cold won’t hurt him.”

“I’m worried about my household goods,

not

’Crets.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Get him out of here, Seaton. Get him out of here without turning the whole room upside-down.”

Curious ’Crets was peering at them from the headboard across the darkened bedchamber, a simian version of Poe’s raven. The large white

10

on his jersey seemed to proclaim him the perfect capuchin, than which no other monkey of that genus was more agile, intelligent, or emblematic of unknown menace. Seaton made no effort to catch him or to call him off the bed. Instead, he gave the dim room a lingering appraisal.

“Is this where you sleep?”

“Get him

off

my headboard!”

“That’s a pretty king-sized bed, Mrs. Crye. You must have shared it with your husband once. It must be lonely sleeping in such a big bed in such a big room without your husband beside you.”

Stevie gaped at the blond young man. Coming from any other male intruder those words would have sounded like the prelude to rape or a proposition as unwanted as it was obvious. Seaton, however, made these tactless comments resonate with a wistful sympathy. That, in its own way, was almost as frightening as a liquorish tongue reaming her ear and an uncouth hand on her breast. In the latter brutal scenario, at least, she could have screamed for help without the least twinge of indecisiveness.

And then Seaton asked, “Did you love your husband?”

“Of course I loved my husband.” Stevie was too shocked by the out-of-left-field nature of the query to make any other reply.

“And he loved you?”

Her shock disintegrated like a tumor under repeated bombardments of electrons from the Clinac 18. “Get your goddamn monkey out of my room!”

Unabashed, Seaton looked at his goddamn monkey. “Here, ’Crets. Here, ’Crets.” He whistled between his front teeth. “Got some Sucrets for you, ’Cretsie boy.” He neared the bed extending a foil-wrapped lozenge, alternately whistling encouragement and hyping the old familiar bribe. “Got a sweet un, ’Cretsie. Got you a really sweet un.”

Like a kid going feet-first off the high dive at the rock pool in Roosevelt State Park, ’Crets sprang from the headboard into the middle of the Technicolor quilt. He bounced once, grabbed the Sucret from Seaton, and landed on the carpet two feet from Stevie. His no-eyes were miniature black maelstroms threatening to spin her into an otherworldly abyss. When Stevie fell back from the capuchin’s stare, ’Crets scampered through the doorway and down the hall into Marella’s room.

Her heart galumphing in her breast, Stevie gritted her teeth and pursued the creature. “Come on!” she shouted at Seaton. “You promised me this wouldn’t happen. You’ve got to catch him.”

Inside Marella’s vast bedchamber, she paused and looked around. ’Crets could be anywhere. Her daughter collected stuffed animals: bears, poodles, crocodiles, armadillos, koala bears, goats, seals, ducks, and Sesame Street critters. Some were lifelike, some mythological, some were polka-dotted or parti-colored parodies of genuine terrestrial fauna—but they occupied every niche, cranny, and bureau top in the room, making a quick sighting of Seaton’s companion unlikely even had ’Crets consented to jump up and down in the middle of this inanimate menagerie.

Stevie peered at the three-story tray assembly across the room in which Marella had stacked many of her plush animals, but the live monkey did not seem to be there. He had gone under one of the beds or concealed himself in the step-down closet about twelve feet to Stevie’s left. This closet had a small inner door opening into a section of attic over the kitchen—a hatch, really—and the last time Stevie had checked, this door had been fastened by a wooden block on a large skewering nail. But now the door to the step-down closet stood conspicuously ajar, and if either Teddy or Marella had peeked into the attic without afterward twisting that block back into place, ’Crets might have fled into the attic’s peculiarly populated darkness, and they’d never get him out. Heat from the kitchen warmed that musty labyrinth even in the winter, making it livable, and its dimensions sometimes seemed greater than those of the kitchen-cum-dining-area it allegedly crowned, especially to intruders not acquainted with the place. The last thing Stevie wanted was a death’s-head capuchin haunting her attic, prowling its cobwebbed promenades with an exit into Marella’s room as handy as a nearby 7-Eleven store. She envisioned the little monster slipping out at night to sit on her daughter’s pillow and refresh himself at her jugular. And if ever Marella propped a plush animal on her pillow before retiring, and if ever Stevie looked in on her in midnight’s detail-obliterating gloom, Stevie would mistake the toy animal for the real-life capuchin and straightway suffer cardiac arrest. . . .