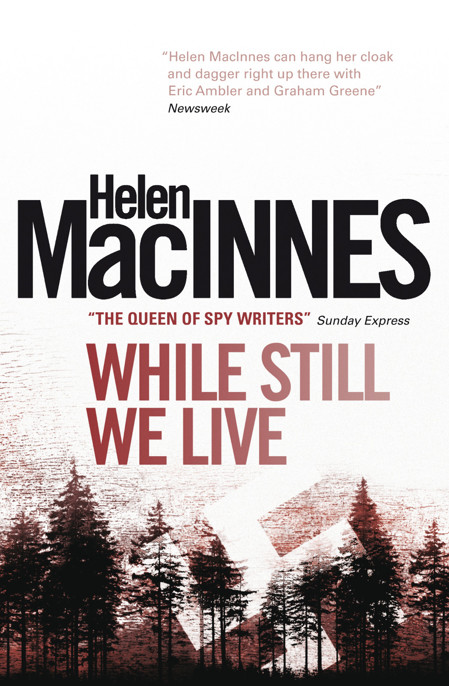

While Still We Live

Read While Still We Live Online

Authors: Helen MacInnes

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #Thrillers, #Espionage, #Suspense

ALSO BY HELEN MacINNES

AND AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

Pray for a Brave Heart

Above Suspicion

Assignment in Brittany

North From Rome

Decision at Delphi

The Venetian Affair

The Salzburg Connection

Message From Málaga

The Double Image

Neither Five Nor Three

Horizon

Snare of the Hunter

Agent in Place

While Still We Live

Print edition ISBN: 9781781161555

E-book edition ISBN: 9781781161616

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: December 2012

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

© 1944, 2012 by the Estate of Helen MacInnes. All rights reserved.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Did you enjoy this book?

We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at:

[email protected]

or write to us at the above address.To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website.

CONTENTS

Poland has not yet perished while still we live!

These are the opening words of the Song of the Polish Legions. It was first sung in the black year of 1797, when Poland had been divided between the three empires of Russia, Prussia, and Austria, and her exiled sons were fighting in the Legions under the gallant General Dombrowski. Thereafter, during the nineteenth century, with its incessant bloody revolts against foreign tyranny, the Song of the Legions spread secretly all over Poland, giving encouragement and hope to all those who were willing to sacrifice themselves for the future freedom of their country. Such was its power and so glorious was its history that it became the national anthem of liberated Poland; and even under new oppressors it is still sung by the Polish people, who refuse to become slaves. The noble truth of its words has been proven by history, past and present: no nation, no cause will ever die if it breeds the kind of man who is willing to sacrifice everything for it, even his life.

END OF A SUMMER

The blinding directness of the sun had gone, but its heat remained. In front of the house, the island of uncut grass baked into brown hay. The pink roses were bleached white. Only the plot of scarlet flowers still held its bright colour. The heavy scent of ripening plants was in the air.

Sheila stood for a moment beside the open window. The truth was, she kept repeating to herself, she hadn’t wanted to leave. There was no use in blaming her irritation on the heat; or on this last-minute packing, too long delayed; or on Uncle Matthews’ latest telegram, which pinpricked her conscience every time she looked toward it and the dressing table. Even now, when she should be elbow-deep in a suitcase, she was still standing at this window, listening to the precise pattern of the Scarlatti sonata which struck clearly up from the little music room. Teresa was playing it well, today. Sheila half-smiled as she imagined the child sitting so very upright, so very serious,

before the piano, while her mother, Madame Aleksander, counted silently and patiently beside her. The difficult passage was due any moment now. Sheila found herself waiting for it, and breathed with relief when it came. Madame Aleksander would be smiling, too. Teresa had managed it.

“Now,” said Sheila, “I can get on with my packing.” But she still stood at the window, her eyes on the driveway which entirely circled the long grass. Thick dust lay white on its rough surface. A flourish of poplars, erect and richly green against the brown harvested fields, formed the entrance gate to the house. There the driveway ended and the road to the village began. Across the road, there was nothing but plain, stretching out towards the blue sky. Here and there, the woods made thick dark patches, beside which other villages, other manor houses, sheltered. But above all, the feeling was one of space and unlimited sky. Unlimited sky... Sheila thought suddenly of bombing planes. She turned back into the room. The smile, which had stayed on her lips since Teresa’s triumph over difficult fingering, now vanished. She began to pack. It was baffling how clothes seemed to multiply, merely by hanging in a wardrobe.

The music lesson was over. The house was silent. And then, downstairs in the entrance hall, the ’phone bell rang harshly. Sheila, by a process of ruthless jamming and forcing, had managed to close the last suitcase. She was locking it, with no small feeling of personal triumph, when Barbara’s light footsteps came running up the staircase, through the square landing which was called Madame Aleksander’s “sewing room,” through Barbara’s own bedroom, and then halted abruptly at the doorway of the guest room. Sheila finished untwisting the key before she

looked up. Barbara had been waiting for this look. She came into the bedroom slowly, dramatically. Her wide eyes were larger than ever with the news she brought.

“Actually finished,” Sheila said, and searched in the pocket of her blouse for a cigarette.

Barbara said, “Sheila, that was Uncle Edward phoning.” She spoke in English, her voice stumbling, in its eagerness, through the foreign language.

“Was it?” Sheila was now looking for the perpetually disappearing matches.

“Sheila, you know quite well that something has happened,” Barbara said reproachfully. Her face showed her disappointment: her excitement was waning in spite of itself.

Sheila relented, and laughed. “All right, Barbara. What’s your news?”

“Uncle Edward.”

“What about Uncle Edward?” Sheila thought of the quiet, forgetting rather than forgetful Professor Edward Korytowski, who was Madame Aleksander’s brother.

“He has just ’phoned from Warsaw.” Barbara was walking about the room now, straightening the pile of books and magazines, arranging the vase on top of the dressing table. She broke into French in order to speak more quickly. “He’s worried about you, and he must be very worried to drag himself away from the Library and his books. He even suggested he was coming here to fetch you, if we didn’t get you away tonight.”

“But the news has been bad for weeks...” Weeks? Months, rather. Even years.

“Well, it must be worse. Uncle Edward has friends, you know, who are in the government. Before he was a professor, he was active in politics, himself. It looks as if someone has

managed to get him away from his manuscript long enough to waken him up again. Certainly, he is very worried. He made me fetch Mother from the kitchen, where she had gone after the piano lesson to attend to something or other. He made me bring her to the ’phone when she was in the middle of preparing a sauce. And now she is so worried that she even forgot to be angry about the sauce. She is coming up to see you as soon as she can get away from the kitchen.”

Sheila found it wasn’t so easy after all to pretend that everything was normal. There was no use getting excited, but on the other hand there was no use disregarding Uncle Edward. He was far from being a sensationalist.

“What did Uncle Edward say, exactly?”

“To me, he said: ‘Is Sheila Matthews still there? In heaven’s name, why? Didn’t I advise her to leave last week at the latest? If she doesn’t leave tonight, I’ll come down and get her and see her on that train, myself.’ And then he told me to bring Mother to the ’phone, and grumbled about a pack of women losing all count of time.”

Sheila looked towards the open window with its square of blue sky and green treetops, watched a large black bee hovering with its sleepy murmur over the windowsill. Yes, one lost all count of time, all sense of urgency here. That was one of the things she had enjoyed most at Korytów.

“Is the wireless set working yet?” Sheila asked.

Barbara’s pretty mouth smiled. “Stefan thinks he has found out what is wrong. Don’t you hear that crackling coming from his room?”

“Peculiar noises are always coming from Stefan’s room,” Sheila gave an answering smile. She had a particular fondness for

Barbara’s fourteen-year-old brother Stefan, the great inventor. The wireless set had been having its monthly overhaul. The result, so far, had been a strong sound of frying at each turn of the dial.

The two girls heard Madame Aleksander’s footsteps, now. They had halted for a moment in her sewing room, before she came through Barbara’s room.

Barbara and Sheila exchanged quick glances. Madame Aleksander’s footsteps told them so much. The underlying worry of the last month, with all its alarms and false reports, was now plain in their eyes.

Madame Aleksander hesitated a moment at the doorway of the guest room, as if she were tired, depressed, loath to give them the news she had brought. The fair hair, fading to platinum, was smoothly braided round the neat head. The bright blue eyes under the straight eyebrows were desperately worried. There was a droop to the corner of her mouth. And then, as she saw the girls watching her so silently, there was the beginning of a smile. It was a good effort, Sheila decided appraisingly, and offered Madame Aleksander the solitary chair.

“I’m afraid we shall have to miss our late afternoon talk, today,” Madame Aleksander said. It was the custom of this house for all the members of the family to gather in Madame Aleksander’s sewing room, and there, in the little white-panelled room with its polished floor and faded brown velvet chairs, with its soft green porcelain stove and its long window looking out between the front pillars of the house, they’d drink a glass of coffee and talk. There was no dearth of conversation in this house. Aunt Marta, who managed the farmlands as her sister looked after the household, would arrive from the fields

or her office. Barbara would leave the books she was reading for the autumn examinations at Warsaw University. Teresa would clatter up the staircase until her mother’s quiet but firm voice reduced her speed to a polite walk. Teresa had been to see her friend Wanda, the little goosegirl, or had rushed round to the stables to see her friend Felix, or had talked with her friend Kazia coming back from the market at Lowicz. (It was Teresa who brought the news of the day. “My friend Wanda,” or “My friend Felix,” she would begin half-way up the staircase, and then would follow a rambling, breathless story. There was a new baby in the village. There was to be a wedding, but not a proper one: there would be no four days of dancing and fun, because the man had been called up for the army. The schoolteacher had come back from his holiday, and there were going to be lessons again once the harvesting was all finished. Wanda’s grandmother had a pain in her back, and you could hear it creak when she bent over the cloverfield.) Last of all to arrive was Stefan, and as soon as he arrived, Aunt Marta would send him away to tidy himself. “Stefan, if you must oil the clocks, please leave the oil where it belongs.

Not

on your hands.” Stefan would smile good-humouredly and obey. Sheila had guessed that the boy only made this appearance, anyway, out of politeness and a sense of duty. He wasn’t interested in the discussions about crops and prices (Aunt Marta), or in the problems of housekeeping or education (his mother), or in Students’ Clubs (Barbara), or in “my friend Wanda” (Teresa). But he hid his boredom well. Perhaps the fact that his two older brothers—the remaining members of the Aleksander family—were so much occupied in Warsaw made Stefan feel the responsibility of being the man of the house.