When Elephants Weep: The Emotional Lives of Animals (32 page)

Read When Elephants Weep: The Emotional Lives of Animals Online

Authors: Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson

Tags: #Animals, #Nonfiction, #Education

Other elephants have made images on paper or canvas, but perhaps none with so little direction as Siri. Carol, an Indian ele-

HUES EU-.P/U.V/S H'EEP

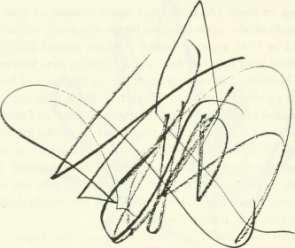

Pig. 10-3A. Drawing done by Siri, an Indian elephant, in pencil on 9" X 12" paper. She drew on a sketch pad that handler David Gucwa held in his lap. Gucwa titled this "I Remember Swans," and included it with others sent to artists Elaine and Willem de Kooning. Before learning that an animal drew them, they admired the flair and originality of the sketches and, when he learned the artist's identity, Willem de Kooning exclaimed, "That's a damned talented elephant."

phant at the San Diego Zoo, was taught to paint as a visitor attraction, and is given commands by her trainer, who tells her when to pick up the brush, supplies her with colors, rotates the canvas so the brush strokes go in different directions, and rewards her with apples. But just as the existence of paint-by-numbers kits does not invalidate the existence of artistic originality, Carol's dutiful paintings do not negate Siri's apparently spontaneous urge to draw.

More recently, Ruby, an Asian elephant in the zoo at Phoenix, Arizona, has been encouraged to paint. Selected because she was the most active—but not the only—doodler among the elephants. Ruby loves to paint and becomes excited when she merely hears the word paint. Blue and red are by far her favorite colors. Biologist Douglas Chadwick reports that she may select other colors that correspond to an unfamiliar object nearby, so that if an orange truck is parked in her view, she may pick orange paint. "A zoo

BEAUTl', THE BK4RS, AND THE SETTING SUN

Fig. 10-3B. This drawing (pencil on 9" x 12" paper), titled "Iris" by Gucwa, was also among diose praised by the de Koonings. Before she was given the opportunity to use pencil and paper, Siri drew in the dust on the floor of her enclosure, scratching designs on the concrete with sticks and pebbles. She was given no rewards for drawing.

visitor was once taken ill while watching Ruby paint, and paramedics were called to the scene. They wore blue suits. It might have been a coincidence that after they left, Ruby painted a blue blob surrounded by a swirl of red." She still doodles in the dirt in her enclosure. A handler thinks the African elephants who share the yard with Ruby are jealous of the attention she gets, because they have begun making highly visible drawings on the walls, using the ends of logs.

A different kind of creativity was seen in rough-toothed dolphins. Trainer Karen Pryor had run out of stunts for the dolphins to perform in shows and decided to reward one of them, Malia, only for performing new behaviors. The trainers waited until Malia did something new, then rewarded her by blowing a whistle and tossing her a fish. Malia quickly learned what was being reinforced that day—tail-slapping, backward tail-walking—and performed that action. In a few weeks they had nm out of new behaviors to reinforce. After several frustrating days, Malia suddenly began performing a dramatic array of wholly new activities, some quite com-

HJIEX ELEPHANTS HTEP

plex. She swam on her back with her tail in the air, or spun hke a corkscrew, or jumped out of the water upside down, or made Hnes on the floor of the tank with her dorsal fin. She had learned that her trainers were not looking for certain actions, but for novelty. Sometimes she was very excited when training sessions were about to start, and her trainers could hardly stop themselves believing that Malia "sat in her holding tank all night thinking up stuff and rushed into the first show with an air of, 'Wait until you see this one!' "

Determined to make a scientific record of this remarkable behavior, the trainers filmed the same process with a second dolphin, Hou. A less optimistic and excitable individual, Hou took longer to catch on, but at the sixteenth training session suddenly performed a burst of novel activities and continued to do new stunts in session after session. Pryor reports that this experience changed Hou lastingly, "from a docile, inactive animal to an active, observant animal full of initiative." Hou also gave more anger signals, having apparently acquired an artistic temperament. Both dolphins began to produce novel behaviors outside training sessions, including opening gates between tanks, leaping over gates, and jumping out of the water and sliding around on the concrete in order to rap trainers on the ankles. While some thought these results showed how intel-Hgent dolphins are, Pryor disagreed: she replicated the experiment with pigeons and ended up with birds that spontaneously lay on their backs, stood with both feet on one wing, or flew into the air two inches and hung there. Such creativity is unexpected in a species usually deemed intellectually unimpressive, but may simply show that, given a chance to be creative, they are smarter than we thought they were.

Culture and tne Concept or Beauty

Human emotions occur in the context of culture, which is not to say that they exist because of culture. Our sense of what is beautiful is significantly influenced by culture. Different human cultures teach somewhat different ideas of what is beautiful. For

BK-mrVy THE BEARS, AND THE SETTING SUN

example, music that delights one group of people may strike members of another culture—or subculture—as discordant, depressing, or ugly. There is more to human perception of beauty than culture, but exactly how much more is unclear. Thus the idea that animals perceive and create beauty leads to the question of whether their aesthetic perception is in some way related to culture.

Culture and its transmission include much that is cognitive, which is not the focus of this book, yet it should be noted that there are many examples of animal culture. In Japanese monkey troops, different troop traditions have been noticed: some troops eat shellfish and some do not; some eat the seed of the muku fruit and some throw it away; some baby-sit for each other and some do not. The most famous example of cultural transmission comes from the story of Imo, the "monkey genius" who invented several feeding techniques, such as throwing handfals of sandy grain into water so that the sand sank and the grain could be scooped off the surface of the water and eaten. Imo's methods were gradually copied by more and more of the monkeys in her troop until they all practiced them.

Elizabeth Marshall Thomas has written of prides of lions in the Kalahari Desert in southern Africa that had a tradition (later lost) of coexistence with humans. In the 1950s, when Thomas first Lived in the Kalahari, lions treated humans—mostly Juwa and Gikwe Bushmen—with resentful respect. They reluctantly allowed humans to drive them away from kills and did not attack humans. In the 1960s the Bushmen were evicted from the area. When Thomas returned in the 1980s, she found that the lions behaved differently. These lions, who no longer lived among a human population, had lost their cultural traditions toward them and seemed all too willing to examine the idea of humans as prey. Thomas also writes that leopards in different areas used different hunting methods for human prey. In what may be described as a cultural shift, a group of olive baboons in Kenya was observed to switch from occasional meat-eating by adult males to a custom of himting and eating prey by males, females, and juveniles, A curious example from captivity is supplied by the chimpanzees at Arnhem Zoo. A dominant male injured his hand in a fight and had to support himself

HUES ELEPHANTS WEEP

with his wrist while walking, whereupon the young chimpanzees began hobbling on their wrists too.

In the University of Washington group of signing chimpanzees where Loulis grew up, the adult chimpanzees had been raised by Allen and Beatrix Ciardner, whom Loulis had never met. One day the Gardners came to visit, an event that was not announced to the chimps. None of the chimps had seen the Gardners for at least a year, and Washoe had not seen tJiem for eleven years. The Gardners walked in. When the chimps saw them they simply sat and stared—highly unusual behavior. They did not give the usual friendly greetings—signs, touches, hugs—given to people they know, nor did they display as they do at strangers, but gazed as if dumbfounded. Except Loulis, who began to display at these unfamiliar people, erecting his hair, standing and swaying, banging on walls. Instantly, Washoe and Dar, who had been sitting on either side of him, seized him. Dar clapped a hand over Loulis's mouth. Washoe took his arm and made him sit down, which he did with an astonished expression. Such treatment was new to him. After a moment Washoe went to the Gardners, signed their names, led Beatrix Gardner into another room, and began to play a game with her that they had played together in Washoe's childhood. In this instance, a piece of cultural information was transmitted to Loulis. The chimpanzees' signing abilities did not extend to making the statement, "These are people we treat with affection and respect," yet Loulis surely was given this message.

Culture has been described as yet another factor that makes humans unique. Examples of cultural transmission of behavior like those above are dismissed as "just interesting oddities." They may be more than that. Cultural transmission may be more widespread among animals than is commonly believed. It has not been argued that any animal species lives in a culture approaching the complexity of any human culture. However, the contention that animals cannot possess a sense of beauty because aesthetics are culture-bound is wholly unproven and there is much evidence to support the contrary.

Just as any two people do not find all the same things beautiful, a person and an animal might disagree. But to dismiss the

210

BK4UTy, THE BEARS, AND THE SETTING SUN

possibility that an animal can sense beauty at all is narrow-minded. Discussing birdsong, Joseph Wood Krutch wrote:

Suppose you had heard at the opera some justly famous prima donna singing "Voi che sapete." . . . You have assumed that [she] genuinely loves music and experiences some emotion related to that which Mozart's aria expresses. . . . But a scientist of another kind—an economist—comes along and says, "I have studied the evidence. I find that . . . the performer really sings for so many thousand dollars per week. In fact she won't sing in public unless she is paid quite a large sum. . . . You may sing in the bath because you are happy and you like to do it. But so far, at least, as professional singers are concerned, they sing for nothing but money." The fallacy—and it is the fallacy in an appalling number of psychological, sociological, and economic "interpretations" of human behavior— is, of course, the fallacy of the "nothing but" . . . there is nothing in human experience or knowledge to make it seem unlikely that the cardinal announcing from the branch of a tree his claim on a certain territory is not also terribly glad to be doing it, very joyous in his realization of his own vigor and artistry. . . . Whoever listens to a bird song and says, "I do not believe there is any joy in it," has not proved anything about birds. But he has revealed a good deal about himself.

Researchers studying elephants in Kenya camp in the middle of the east African bush. Sometimes at night the people sing and play guitars and the elephants draw near to listen. Perhaps they are merely curious, but perhaps they take pleasure in the music. Human curiosity should allow us to ask whether elephants find beauty in music, just as the human sense of beauty allows us to appreciate the image of these large beasts moving slowly through the darkness listening to the songs.

Tne Religious Impulse, Justice, and tne Inexpressible

While nonhuman animals show clear evidence of emotional lives, they should not be considered emotionally identical to humans. This would be true anthropomorphic error, inaccurate projection. We are all beings together, but we are not the same—neither higher nor lower, just distinct.

Much past discussion of animals and emotions has been directed primarily at arguing that certain emotions are the property of humanity alone. To show that, on the contrary, some animals feel some emotions, still means that the question must be asked anew in particular instances. If hippos can feel compassion, that does not mean that a particular hippo feels compassion at a particular time. Similarly, if buffalo are capable of love, this does not necessarily mean that they can feel shame. So it is still possible that there are emotions people feel that no other animals feel. Leaving aside the unimpressive history of human attempts to claim uniqueness, it should be conceded that many species do have attributes that no others have. Pelicans have unusual bills, elephants have trunks, platypuses have poison spurs; perhaps human beings can claim religious awe.