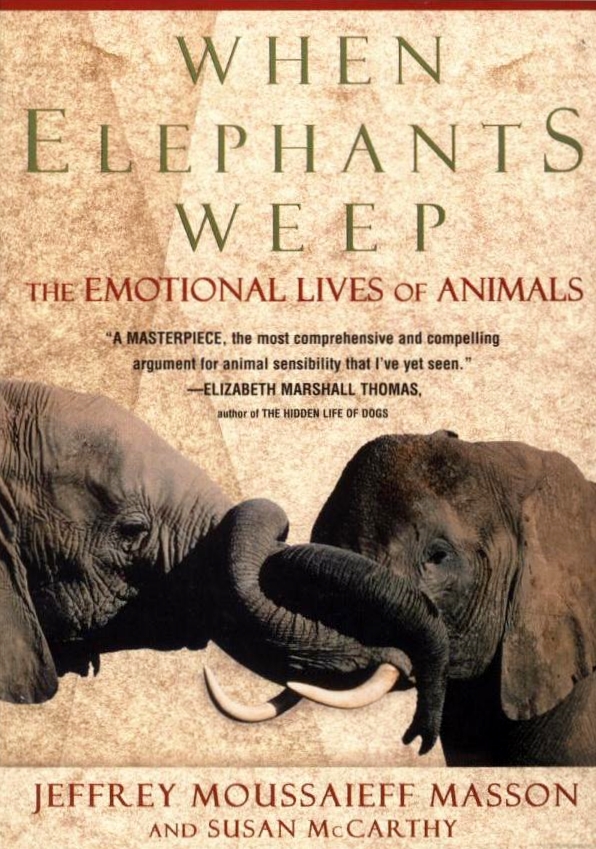

When Elephants Weep: The Emotional Lives of Animals

Read When Elephants Weep: The Emotional Lives of Animals Online

Authors: Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson

Tags: #Animals, #Nonfiction, #Education

For the Fu and Fiona

Contents

11 The Religious Impulse, Justice, and

the Inexpressible 212

Conclusion: Sharing the World with Feeling Creatures 226

Notes 231

Bibliography 210

Index 283

vin

Acknowledgments

In the process of researching this book we talked to many scientists, animal trainers, and others whose expertise was invaluable. We would particularly like to acknowledge the help of George Archibald, Mattie Sue Athan, Luis Baptista, Kim Bartlett, John Beckman, Mark Bekoff, Tim Benneke, Joseph Berger, Nedim Buyukmihci, Lisa De Nault, Ralph Dennard, Pat Derby, Ian Dunbar, Mary Lynn Fischer, Maria Fitzgerald, Lois Flynne, Roger Fouts, William Frey II, Jane Goodall, Wendy Gordon, Donald Griffin, David Gucwa, Nancy Hall, Ralph Heifer, Abbie Angharad Hughes, Gerald Jacobs, William Jankowiak, Marti Kheel, Adriaan Kortlandt, Charles Lindholm, Sarah McCarthy, David Mech, Mary Midgley, Myrna Milani, Jim Mullen, Kenneth Norris, Cindy Ott-Bales, Joel Parrott, Irene Pepperberg, Leonard Plotnicov, Karen Reina of Bristol-Myers Squibb, Diana Reiss, Lynn Rogers, Vivian Siegel, Barbara Smuts, Elizabeth Marshall Thomas, Ron Whitfield, and Gerald S. Wilkinson, among others, for their patience in talking to us. We are also grateful to Jennifer Conroy, Joanne Ritter, Mike Del Ross, and Kathy Finger of Guide Dogs for the Blind in San Rafael. Any errors we have made and any wild

ACKNOHTEDGMENTS

speculations, particularly those deemed scientifically disreputable, are not to be laid at their doors.

More personal thanks are owed to our friends and family also for their support and real assistance, especially Daniel Gunther, Joseph Gunther, Kitty Rose McCarthy, Martha Coyote, John McCarthy, Mary Susan Kuhn, Andrew Gunther, Barbara and Gerald Gunther, Thomas Goldstein, Martin Levin, and Bernard Taper; and Daidie Donnelley, Fred Goode, Justine Juson, Marianne Lo-ring, Jane Matteson, Eileen Max, and Barbara Sonnenborn.

We also want to thank Elaine Markson for being a wonderful agent; Tony Colwell for having faith in this idea all along; Steve Ross for his enthusiasm and his indispensable help in making this the book it is; as for Kitty, only Kitty knows what Kitty is owed.

Wken Elepnants Weep

Prologue:

Searcning tne Heart

or tne Otner

'''The hidian elephant is said sometimes to weep. "

Charles Darwin

Animals cry. At least, they vocalize pain or distress, and in many cases seem to call for help. Most people believe, therefore, that animals can be unhappy and also that they have such primal feelings as happiness, anger, and fear. The ordinary layperson readily believes that his dog, her cat, their parrot or horse, feels. They not only believe it but have constant evidence of it before their eyes. All of us have extraordinary stories of animals we know well. But there is a tremendous gap between the commonsense viewpoint and that of official science on this subject. By dint of rigorous training and great efforts of the mind, most modern scientists— especially those who study the behavior of animals—have succeeded in becoming almost blind to these matters.

I was led to my interest in animal emotions by experiences with animals—some traumatic, some deeply touching—as well as by the seeming opacity and inaccessibility of human feelings compared with their undiluted purity and clarity, at times, in my animal friends, and especially of animals in the wild.

In 1987 I visited a south Indian game reserve known for its wild elephants. Early one morning I set out with a friend to walk in

xin

PROLOGUE

the forest. After a mile or so we came across a herd of about ten elephants, including small calves, peacefully grazing. My friend stopped at a respectful distance, but I walked closer, halting about twenty feet away. One large elephant looked toward me and flapped his ears.

Knowing nothing about elephants, I had no idea this was a warning. Blissfully ignorant, as if I were in a zoo or in the presence of Babar or some other story-book elephant, I felt it was time to commune with the elephants. Remembering a Sanskrit verse for saluting Ganesha, the Hindu god who takes elephant form, I called '''Bhoh, gajendra'" —Greetings, Lord of the Elephants.

The elephant trumpeted; for a second I thought it was his return greeting. Then his sudden, surprisingly agile turn and thunderous charge in my direction made it all too clear that he did not participate in my elephant fantasies. I was aghast to see a two-ton animal come hurtling toward me. It was not cute and did not resemble Ganesha. I turned and ran wildly.

I knew I was in real danger and could feel the elephant gaining on me. (Elephants, I later learned in horror, can run faster than people, up to twenty-eight miles an hour.) Deciding I would be safest in a tree, I ran to an overhanging branch and leapt up. It was too high. I ran around the tree and raced into tall grass. Still trumpeting menacingly, the elephant came running around the tree in close pursuit. He clearly meant to see me dead, to knock me down with his trunk and trample me. I thought I had only a few seconds to live and was nearly delirious with fear. I remember thinking, "How could you have been so stupid as to approach a wild elephant?" I tripped and fell in the high grass.

The elephant stopped, having lost sight of me. He raised his trunk and sniffed the air, searching out my scent. Fortunately for me they have rather poor vision. I realized I had better not move. After a few long moments he turned away and raced off in another direction, looking for me. Soon I quietly picked myself up and, trembling, made my way slowly back to where my terrified fi-iend had stood watching the whole episode, convinced she would witness my death.

Rudimentary knowledge of elephants would have kept me

PROLOGUE

safe: a herd with small calves is particularly alert to danger; elephants don't like their space invaded; flapping ears are a direct warning. The encounter itself was nothing but a projection of my own wish that a wild elephant would want to meet me.

It was wrong to think that I could communicate with a strange elephant under these circumstances. Yet he communicated very clearly to me: he was angry and I should leave. I believe this is a realistic description.

By contrast with animals, people's emotions are often distanced. For example, I experience heightened emotions in dreams —anger, love, jealousy, relief, curiosity, compassion—to a degree of intensity that is not paralleled in waking life. To whom do those emotions belong? Are they mine? Are they what I imagine a feeling to be like? In the dream there is nothing abstract about them: \feel extraordinary love, always for people for whom, in fact, I do feel love, just not to that degree. As a former psychoanalyst, I thought that these were feelings I had somehow repressed in my day life, and only had access to the real feelings in my night life. I theorized that the feelings were real, only access to them was barred. The feelings were always there, but could only become conscious at certain moments when some part of me was off guard—asleep, as it were. Somehow my ego had to be circumvented, an end run needed to be made, and they were there waiting, pure, unsullied, ready. Might animals have the more ready access to this feeling world that was largely denied my waking self?

Then there is the question of the feelings of others. What could be more interesting than what others/f^/? Do they feel the same things I do? I have found it hard to find out by talking, or even by reading. Songs, poems, literature, walking in the woods, evoke certain feelings. Sometimes they are strange, complex, inexplicable, even bizarre, often intense beyond comprehension. Where does this come from? I have long wondered. Why am I feeling this? What am I feeling? How could I name this?

In my training as a psychoanalyst, I discovered that analysts were not really all that interested in emotions. Or rather, they confined their interest to interpreting an emotion's meaning to the psyche or discussing whether an emotion was appropriate or inap-

I'RULUGUE

propriate. I thought appropriateness was a ridiculous category. Emotions simply were. Moreover, they seemed to come unbidden. They were mysterious guests, hard to capture. Sometimes I thought I could feel something for only a brief second, or fraction of a second, but then it was gone and could not be recalled. Sometimes I would wake up in the middle of the night and remember a feeling I had once had and experience a kind of loss.

Psychoanalysis purports to be about feelings, especially deep feelings. For psychoanalysts the essence of a person is not what is thought or achieved, but what is felt. The standard, almost humorous, therapist question, "How do you feel about that?" turned out to be quintessential and hard to answer. We do not always know— hence the notion, early in Freud's work, of unconscious emotions, ones to which we are denied access. The early goal of psychoanalysis to make the unconscious conscious was directed toward bringing feelings into awareness, raising submerged emotions to the surface. Yet the question of emotions in dreams was and is barely touched in the psychological literature.

What fascinated me about animals was the ready access they seemed to have to their emotions. No animal, it seemed to me, needed to dream to feel. They demonstrated their feelings constantly. Annoy them, they have no hesitation in showing it. Please a cat, it purrs and rubs itself against you. What could appear as contented as a cat? A dog wags its tail and looks more genuinely pleased to see you than any human. W^at could appear as happy as a dog? Could anything seem as peaceful as a cow? Or are these merely human projections?

As a child, I had a duck that seemed to think I was its mother. It followed me everywhere. When we went on vacation, a neighbor offered to care for it. On our return, I eagerly asked how my duck was and he replied, "Delicious." I became a vegetarian that day. I still cannot bear to eat anything with eyes. The reproach is too deep.

I love dogs; it has always been clear to me that they lead extremely intense emotional lives. "No, Misha, no walk just now." What? The ears would cock. Can I have heard right? "Sorry, Misha, but no." Unmistakable. The ears flop. Misha would throw himself

PROLOGUE

onto the floor. There was no mistaking the pure disappointment he was feeHng. Just as unmistakable was his intense joy when I would say, "Okay, get your leash, we're going for a walk," and the sheer pleasure Misha felt on his walks, his delight at racing ahead, chasing leaves, doubling back, tearing off into the forest and returning behind and ahead of me. The contentment when we got home, built a fire, and I sat down to read, he to rest next to me, his face on my knee, was equally apparent. As he grew old, and could no longer walk as well, I could almost see him visit the scenes of his earlier Hfe in his imagination. Nostalgia, in a dog? Well, why not? Darwin thought it possible.

In his book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, Charles Darwin had dared to imagine a dog's conscious hfe: "But can we feel sure that an old dog with an excellent memory and some power of imagination, as shewn by his dreams, never reflects on his past pleasures in the chase? and this would be a form of self-consciousness." Even more evocatively, he asked: "Who can say what cows feel, when they surroimd and stare intently on a dying or dead companion?" He was unafraid to speculate about areas that seemed to require further investigation.

Another reason I began thinking in some depth about animal emotions was the common experience of going to a zoo. We have all seen the look of forlorn sadness on the face of an orangutan, wolves pacing nervously up and down, gorillas sitting motionless, seemingly in despair, or perhaps having abandoned all hope of ever being fr^ee.

A pivotal book in my thinking about animal emotions was Donald Griffin's The Question of Animal Awareness. Attacked in many quarters upon its publication in 1976, it discussed the possible intellectual lives of animals and asked whether science was examining issues of their cognition and consciousness fairly. While Griffin did not explore emotion, he pointed to it as an area that needed investigation. Convincing and intellectually exciting, it made me want to read a comparable work on animal emotions, but I learned that there was almost no investigation of the emotional lives of animals in the modern scientific literature.

Why should this be so? One reason is that scientists, animal

PROLOGUE

behaviorists, zoologists, and ethologists are fearful of being accused of anthropomorphism, a form of scientific blasphemy. Not only are the emotions of animals not a respectable field of study, the words associated with emotions are not supposed to be applied to them. Why is it controversial to discuss the inner lives of animals, their emotional capacities, their feelings of joy, disappointment, nostalgia, and sadness? Jane Goodall has recently written of her work with chimpanzees: "When, in the early 1960s, I brazenly used such words as 'childhood,' 'adolescence,' 'motivation,' 'excitement,' and 'mood,' I was much criticized. Even worse was my crime of suggesting that chimpanzees had 'personalities.' I was ascribing human characteristics to nonhuman animals and was thus guilty of that worst of ethological sins—anthropomorphism."