War Without Garlands: Operation Barbarossa 1941-1942 (74 page)

Read War Without Garlands: Operation Barbarossa 1941-1942 Online

Authors: Robert Kershaw

This lack of balance was hinted at by Generalfeldmarschall von Bock, who declared on 3 December, ‘if the attack is called off then going over to the defensive will be very difficult’. The last card had been staked on Moscow’s fall. In fact, von Bock admitted, This thought and the possible consequences of going over to the defensive with our weak forces have, save for my mission, contributed to my sticking with this attack so far.’ Within two days Panzergruppe 3 reported ‘its offensive strength is gone’. It could only hold its positions if the already decimated 23rd Infantry Division remained under command. Von Bock was also informed by General von Kluge, the commander of Fourth Army, that Hoepner’s planned attack with Panzergruppe 4 should not go ahead.

(4)

Late that same day Generaloberst Guderian advised that his Second Panzer Army should ‘call off the operation’. He said the ‘unbearable cold of more than −30°C was making moving and fighting by the tired, thinned-out units extremely difficult’. German tanks were breaking down while the Russians, did not.

Oberstleutnant Grampe, commanding a tactical headquarters with the 1st Panzer Division, reported the same day that his Panzers had been put out of action by low temperatures, which had dropped to −35°C. ‘The turrets would not revolve,’ he stated, ‘the optics had misted up, machine guns could only fire single rounds and it took two to three crew members to depress tank gun barrels, only achievable if they stamped down on the main barrel where it joined the turret block.’ His unit was not equipped to cope with such conditions. Cases of first- and second-degree frostbite were beginning to emerge. ‘The division,’ he assessed, was practically immobile.’

(5)

The German front went over to the defensive, frozen inert at the very moment the Russian offensive was about to strike. Temperatures plummeted from −25°C on 4 December to −35°C on the 5th and to −38°C the following day. Co-ordinated operations appeared impractical. German troops sought only shelter.

The new Soviet armies had been assembled together for only two to three weeks. They were a mixture of fresh Siberian units, burned-out veteran formations and briefly trained militia or reservists. Many lacked equipment and there were shortages of ammunition. Officers and NCOs were inexperienced. Tanks were dispersed among about 15 tank brigades with about 46 machines in each. A high proportion of the units were fresh and unbloodied in battle, and, unlike the enemy, they were warmly clad. Their motivation was superior to that of the German, whose moral component of fighting power had bled profusely, perhaps mortally, since September. As in the case of the original ‘Barbarossa’ invasion, Soviet counter-stroke formations had deployed in such numbers that, even if they were discovered, the difficulty of moving troops and equipments to oppose them was impractical. A‘checkmate’ configuration had been created in these Arctic conditions. They possessed massive local superiority and, above all, total surprise.

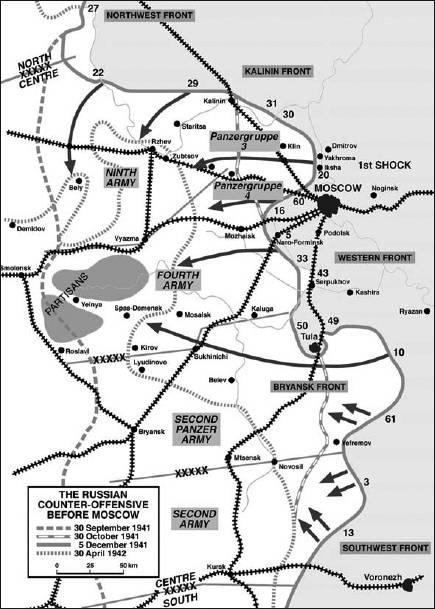

In mind-numbing, freezing conditions during the early morning hours of 5 December, the Soviet Twenty-ninth Army attacked across the ice-covered Volga west of Kalinin. They penetrated the German Ninth Army line for up to 10km before they were checked. On the following morning, which dawned clear with temperatures of −38°C, the soldiers of the West and South-west Fronts went over to the offensive. Drifting snow and near-Arctic conditions seriously impeded the final build-up, resulting in piecemeal attacks which gradually achieved a cumulative and unstoppable momentum.

The IInd Battalion of Schützen Regiment 114, part of 6th Panzer Division, in the village of Stepanowo immediately east of the Moscow-Volga canal line, reported on 6 December:

‘During the course of the morning there were signs of unrest among the civil population. The explanation – that Stepan-owo would be taken by the Russians, and that the Germans would leave – was laughed at by the German soldiers. Radio enquiries, however, confirmed the opposite. Soon part of the 7th Panzer Division was coming back along the Stepanowo-Shukowo road.’

A visit by General Model, the corps commander, to 6th Panzer Division headquarters at 10.00 hours, ‘produced a surprising direction,’ admitted the operations officer (1a). Model assessed Panzergruppe 3 had insufficient strength to hold the present line ‘against an enemy who had introduced an astonishing infusion of strength’ and was directing his main efforts against the northeastern flank. ‘As a consequence,’ Model directed, ‘the front must be shortened.’ Engineer rear area route and obstacle reconnaissance was ordered ‘at once’. The logistics (1b) officer was told to ferry back wounded and to begin the necessary reorganisation of the logistic rear support services.

(6)

Model’s corps was about to embark on its first retreat of the war. It was the third disappointment the 6th Panzer Division had experienced short of victory. They were halted at Dunkirk in 1940 and again before Leningrad in September 1941. Moscow was also to be denied them.

Artillery soldier Pawel Ossipow took part in the barrages that preceded the Russian attack on 6 December. As the infantry moved forward, their inexperience became increasingly apparent. ‘Particularly the youngsters,’ he said, were exposed to a lot of blood and witnessed the horror of war for the first time as wounded men died in deep snow at temperatures of −30°C.’ Pjotr Weselinokov also recoiled at the sights of‘our first battle’. He likened it to an abattoir. ‘The worse thing of all,’ he reflected,‘were the freshly killed bodies of soldiers left steaming’ where they lay in the frozen temperatures. ‘The air was filled with the peculiar stench of flesh and blood.’

(7)

On the second day of the offensive, attacks gathered momentum. Thirty-first Army joined the stalled Twenty-ninth Army grappling with the German Ninth Army to the north, on the Kalinin front. They failed to force a passage across the Volga south of Kalinin. Thirtieth Army, however, made a deep 12km penetration into the Panzergruppe 3 flank north-east of Klin. First Shock and Twentieth armies crashed into both Panzergruppen 3 and 4 on a front from Yakhroma to west of Krassnaya Polyana. Some gains were made south of the latter in desperate fighting. Tenth Army, meanwhile, struck Second Panzer Army at the east point of the Tula bulge with one rifle division and two motorised infantry regiments. The rest of the army was still marching up from Syzran. South-west Front’s Second and Thirteenth armies began to apply pressure at Yelets at the southern base of the Tula bulge.

Michael Milstein, attached to Zhukov’s staff, remembered that‘gradually confidence came, the first counter-attacks were showing results’. But this was at considerable cost. Artillery soldier Pawel Ossipow said:

‘There were many wounded, particularly among the [hand-towed] machine gun crews. While all the others had to keep moving forward, nobody could help them. We detached one of our men, who had to administer first aid, to report them to the rear area services, so that the motorised unit following behind could pick them up.’

‘One could actually see signs,’ said Michael Milstein, ‘that it may be conceivable the Hitler Army might be defeated.’ This was not expressed in the typical inflated ‘Great Patriotic War’ rhetoric. Milstein, a staff officer, objectively assessed the achievement as being ‘no miracle’, rather ‘it was the result of planned operational preparation… Certainly there were losses and disadvantages,’ he concluded, ‘but it was a properly executed operation.’ Lieutenant – and later historian – Dimitrij Wolkogonow, observed that the German Army ‘appeared out of breath,’ and that ‘the Soviet Army counter-offensive was fully unexpected’. This was also the case for the civilian population. Pawel Ossipow grimly pointed out, ‘we also saw a lot of dead civilians, old women and children.’ They were completely caught out by the sudden resurgence of operations in such terrible weather. ‘Many of them ran naked into the open during the attack,’ said Ossipow. ‘It was awful.’

(8)

On 5 December German medic Anton Gründer was on duty until 06.00 hours in the Ninth Army sector.

‘As I was making something to eat, all hell broke loose outside. Everything was pulling back, Panzers, artillery guns, vehicles and soldiers – singly or in groups. They were all in shock. There were no more orders; everybody took up the retreat and looked no further forward than what he felt he might reach. Most vehicles didn’t start because of the terrible cold; despite that we were able to take most of the medical supplies with us. We tried to keep together with the remnants of the company so far as possible, but whoever fell out, was lost.’

Caring for the wounded in the confusion of the retreat was an almost unsupportable burden. ‘Dreadful scenes were played out before our eyes,’ admitted Gründer. Many wounded presented themselves for treatment with emergency bandages that had been applied more than a week before.

‘One soldier had an exit wound through the upper part of his arm. The whole limb had turned black and the pus was running from his back down to his boots. It had to be amputated at the joint. Three soldiers smoked cigars throughout the operation because the stench was so unbearable.’

(9)

The German retreat took many forms, varying between disciplined order and panic-driven flight. Whatever the recriminations and debates between army group and higher headquarters over its extent, it continued to run. Motorised formations, which had achieved the glory of the advance, were fortunate in being able to withdraw to a plan of sorts. They had a chance. The infantry, who through sheer brute strength and willpower had underpinned the offensive and arrived last, were the most exhausted. Being foot-borne, their survival chances were correspondingly less. Caught in the open, with no prepared bunkers to their rear, many perished anonymously in hard-fought rearguard actions.

The Soviet counter-stroke before Moscow in December 1941 achieved complete strategic and operational surprise. By Christmas the Germans had lost all the ground they had won during the final drive following the Orscha conference. The first phase of the Soviet counter-offensive cleared the Germans before Moscow, but the second phase did not succeed in destroying the Ostheer. Soviet operational inexperience resulted in some reverses before a tortuous yet continuous German front was shored up by April 1942. Army Group Centre had lost its offensive capability.

Leutnant Heinrich Haape’s leave train was halted, just as he was departing for Germany. ‘Every man is to return at once to his unit and report for duty,’ they were told. Muttered protests stopped when it was announced the Russians had broken through at Kalinin. ‘There was silence among the men now,’ Haape recalled, ‘nobody swore – the matter was too serious for swearing even.’

‘And where are the Russians?’ asked Haape, when he rejoined his division. ‘Everywhere,’ was the response, ‘nobody seems to know precisely where.’

(10)

In the north the deepest Russian advance was made by General Lelyushenko’s Thirtieth Army. It soon reached the Moscow-Leningrad highway, jeopardising the link between Panzergruppe 3 and von Kluge’s Fourth Army. On 13 December Klin was reached, threatening a partial encirclement with First Shock Army advancing due west. It took two days of fierce fighting to clear the town. Sixteenth and Twentieth Armies, meanwhile, captured Istra on the original Army Group Centre axis of advance toward Moscow. Solnechnogorsk was abandoned by the Germans on 12 December. South of Moscow, Guderian’s main supply artery, the Orel-Tula line, was menaced by advancing Soviet forces as the Fiftieth and Tenth Armies succeeded in separating Second Panzer Army from von Kluge’s Fourth Army to its north. During the first phase of the Soviet counter-offensive, which lasted until Christmas, the Russian armies took back all the ground the Germans had won during their final drive on Moscow after the Orscha conference.

Pawel Ossipow pondered the cumulative impact of successive German setbacks:

‘On the second or third day of the counter-offensive, on 7 or 8 December it dawned on us that our attack was going successfully, morale amongst all the soldiers, sergeants and officers soared. From then on we pushed forwards in order to overtake the Germans before they could set villages on fire. As a rule they torched everything before a withdrawal.’

(11)

Devastating villages was universal practice across the front for both sides. It had already occurred during withdrawals around Leningrad. Gefreiter Alfred Scholz, with the 11th Infantry Division, had participated in the systematic wasting of territory whereby civilians were pitilessly set outside in cruel freezing temperatures down to −30° and −40°C.

‘I personally saw,’ he admitted, ‘Russian women and children lying frozen in the snow’. As the withdrawal started in the central sector, the excesses visited on the population during the advance were repeated during the retreat. Obergefreiter Wilhelm Göbel, with Infantry Regiment 215 (part of 78th Division) south-west of Moscow, recalled the pain of constant withdrawals. ‘While accommodated in these villages,’ he admitted, ‘the Germans were taken in hospitably by the civilian population. They washed our underclothes, cleaned our boots and cooked potatoes for us.’ When his IInd Battalion commander, Major Käther, received the order ‘to burn down various villages and pollute wells,’ he remonstrated, stating that he ‘disagreed with such senseless destruction.’ But duty and an in-bred sense of order and discipline overcame his doubts. ‘An order is an order,’ he resolved. ‘We had to do our duty as soldiers and had strictly to obey’

(12)

Each rearguard was instructed to torch villages as it withdrew. When Pawel Ossipow reached his own village near Volokolamsk he found his own house had been burned to the ground and his family had fled. There was some compensation in the fact that ‘liberated villagers always welcomed us and offered hospitality, which pleased us’.

(13)