War: What is it good for? (48 page)

Read War: What is it good for? Online

Authors: Ian Morris

But like nearly everything in this brave new world, the Soviet lead was short-lived. Two years later the United States also had working ICBMs, and in 1960 both sides mastered the art of launching them from submarines. This ruled out the possibility of a first strike killing enough of the enemy's missiles to prevent him from shooting back and shifted the calculus again.

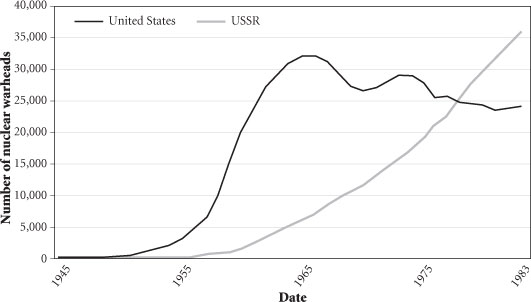

In the early 1960s, the United States still had a nine-to-one nuclear superiority over the Soviets (

Figure 5.14

), and the Department of Defense projected that an American first strike would be able to kill 100 million people, probably bringing down the Soviet Union. However, the report went on, a Soviet counterstrike against the bigger cities of the United States and its allies would kill 75 million Americans and 115 million Europeans, bringing down most of the rest of the Northern Hemisphere.

Figure 5.14. Overkill: Soviet and American nuclear arsenals, 1945â83

The age of mutual assured destruction, with its almost too perfect acronym, MAD, had arrived. Massive retaliation now meant that the United States, as well as the Soviet Union, would be committing suicide, which naturally made the New Look rather less attractive. Unknown unknowns were returning. In 1961, wondering whether the newly installed president, John F. Kennedy, would really risk New York to save his stake in Berlin, the Soviets pushed harder than usual in the endless confrontation over that

divided city. Fear clutched the world as politicians postured and threatened. Finally, the communists compromised and built a wall down the middle of the city, but the next year things got even worse. “Why not throw a hedgehog at Uncle Sam's pants?” Khrushchev asked, and sent Soviet missiles to Cuba. For thirteen heart-stopping days, the worst-case scenario seemed to have arrived. It was like the 1910s all over again, but this time with doomsday devices.

The world woke up with a start to what it had wrought. In the liberal democracies of the American alliance, millions marched in campaigns for nuclear disarmament, sang protest songs, and lined up to see

Dr. Strangelove. Coming of Age

-ism's assumption that war was good for absolutely nothing, under any circumstances, swept the field.

But none of this solved the planet's problem. As in every earlier age, so long as anyone thought that force might be the least bad answer to their problems (or so long as anyone thought that someone else might be thinking that), no one dared forgo weapons, and as with every vicious new weapon since the first stone ax, once the bomb had been invented, it could not be “disinvented” (Eisenhower's word). If all the warheads in the world were scrapped, they could be replaced in a matter of monthsâwhich might mean that banning the bomb would be the most dangerous action imaginable, because a treacherous enemy might secretly rebuild its arsenal and launch a devastating first strike before its rule-abiding rival could make enough bombs to deter it.

Despite the runaway success of “War” and dozens of lesser protest songs in the late 1960s, most people apparently agreed with this logic. No nuclear-armed electorate ever voted in a party preaching disarmament. When the British Labour Party did promise to ban the bomb, it went down to an epic defeat (one of its own Members of Parliament called its manifesto “the longest suicide note in history”).

The cold-eyed men who handled the realities of nuclear war looked for more practical solutions. Some of these, such as installing a direct phone line (via relays in London, Copenhagen, Stockholm, and Helsinki) between Washington and Moscow, were easy. Others, such as reducing the immense stockpiles of warheads, were not. The United States stopped expanding its arsenal in 1966, but the Soviets did not follow suit for twenty years. (As one American secretary of defense observed, “When we build, they build; when we stop, they build.”)

The most difficult step of all was finding strategies to contest the inner rim without bringing on the end of days. The American answer was a new policy of flexible response. Instead of threatening to kill hundreds of millions over any disagreement, the United States would react in proportion to the threat. But how would it decide what was proportionate? This definitional issue quickly raised its head in the wake of the European empires' retreat from Southeast Asia. Americans agreed that keeping a foothold in the inner rim in this distant corner of the world was not important enough for nuclear war, but was it worth the bones of American soldiers? In his first year in office, Kennedy had grumbled, “The troops will march in; the crowds will cheer ⦠Then we will be told we have to send in more troops. It's like taking a drink.” All the same, he sent eight thousand advisers to South Vietnam. Two years later, there were twice as many. Four years after that, U.S. marines splashed ashore at Danang, and by 1968 half a million Americans were fighting in Vietnam (

Figure 5.15

).

Figure 5.15. Search and destroy: the U.S. 1st Air Cavalry Division scours the coastal lowlands of Binh Dinh Province, South Vietnam, in the endless hunt for insurgents (January or February 1968).

Putting boots on the ground just brought on a flood of further decisions. Was interning civilians, a tried-and-true method for cutting off supplies to insurgents, proportionate? Yes, the White House decided. What about bombing North Vietnam? Sometimes. Or invading North Vietnam? No, because that might provoke Soviet escalation. Bombing and raiding communist positions in supposedly neutral Cambodia struck President Nixon as proportionate, but many Americans disagreed. Riots broke out; the National Guard shot four dead in Ohio. Consequently, when it came to the bigger step of interrupting communist supplies by building a fortified line across Laosâa militarily obvious move, which, South Vietnamese

generals argued, would “cut off the North's front from its rear”âno president would say yes.

The war dragged on, ultimately killing three or more million people. But despite this unsatisfactory beginning, NATO applied flexible response to Europe too. Here, war would mean the mother of all blitzkriegs. Under cover of the biggest air and artillery bombardment in history, seven thousand Soviet tanks would smash into the thin defensive screen along the inner German frontier, while crack troops arriving by parachute or helicopter sowed chaos a hundred miles to the rear. As the opening battles raged, those NATO planes that survived the initial air raids would strike all the way to Poland to shatter the second, third, and fourth echelons of Soviet armor before they reached the battlefield, while infantry hunkered down to blunt the first wave of Soviet tanks before it could break through the Fulda Gap or across the North German Plain.

NATO generals pinned their hopes on the apparent lessons of Egypt and Syria's attack on Israel in 1973, when, for a few days, poorly led and

trained Arab infantry armed with wire-guided antitank missiles had fought superbly led and trained Israeli tank crews to a standstill. It took less than two weeks for the Israelis to adapt, counterattack, and annihilate the Arab armies, but NATO gambled that their troops could hold out longerâlong enough, the hope was, for American forces to rush across the Atlantic, pick up pre-positioned heavy equipment, and drive the Soviets back.

This was much the way General John Hackett (a former commander of British forces in West Germany) imagined a war playing out in his widely read 1978 novel,

The Third World War

. In his story, flexible response worked perfectly. After seventeen days of conventional battle the Soviet offensive stalled, and with American troops arriving to stiffen the line and even push back, the Soviets escalated. They launched a single SS-17 missile with a nuclear warhead, destroying Birmingham, England. Three hundred thousand died. NATO responded proportionately, with a nuclear strike on Minsk. The unstable Soviet regime then collapsed.

I happened to be living in Birmingham in 1978 (about two miles from Winson Green, Hackett's ground zero), and I did not like his prophecy one bit. But the reality, as the general knew perfectly well, would probably have been much worse. NATO anticipated being the first to go nuclear, using “tactical” devices (often equivalent to half a Hiroshima) to stop breakthroughs and also to signal that the attack must end. If Moscow ignored the message, bigger bombs, shells, and warheads (typically worth half a dozen Hiroshimas) would be used, and if there was still no response by the time Soviet tanks were sixty miles into West Germany, the gloves would come off.

Unfortunately, the Soviets showed not the slightest intention of thinking about H-bombs as subtle signals. Their plan called for tanks to reach the Rhine in two weeks and the English Channel and Pyrenees after another four. To accomplish this, the first echelon would use twenty-eight to seventy-five nuclear weapons to rip holes in the NATO line, and the second would fire another thirty-four to a hundred during its armored breakout. Expecting NATO to reply in kind, Soviet troops were equipped to fight on battlefields drenched in chemicals and radiation, concentrating quickly for attacks and then dispersing. West Germany would suffer several hundred Hiroshimas, killing most of the people who lived there. By that point, the ICBMs would be roaring over the North Pole. As Moscow saw it, a few days of total war would devastate both homelands, but once the warheads were used up, conventional fighting would continue until one side could go on no longer.

The official Soviet line was optimistic (probably, given what we now know about their atrocious infrastructure and organization, overoptimistic) about winning, but no one was actually looking forward to a war like this. Consequently, amid fierce debates, both superpowers started drifting toward an understanding (dressed up with the name “détente”) that would allow them to muddle through despite the inadequacy of flexible response as a strategy of deterrence. Talks about limiting nuclear weapons began in 1969, and in the 1970s the Soviets made concessions on human rights. Americans sold them grain and lent them dollars to make up for the mushrooming failures of collective farms and communist economies, and astronauts and cosmonauts joined hands in orbit.

It all looked good, but none of it altered the realities. Two semi-global empires with enough firepower to destroy civilization remained locked in a competition over the inner rim; the inner rim continued to be run largely by unstable, unreliable proxies with their own agendas; and neither side could afford to lose.

The strategic tug-of-war surged first one way, then the other. In 1972, President Richard Nixon scored a gigantic coup when Moscow's former client Mao decided that he did not hate the United States as much as he hated the Soviet Union. The strategic net tightened around Russiaâbut just a year later, the newest Arab-Israeli war wiped out many of the United States' gains. Arab oil producers quadrupled their prices, tipping the American alliance into economic crisis while flooding the oil-exporting Soviet Union with cash. The economic slowdown, anxieties over how to handle nuclear parity with the Soviets, and recriminations over the Vietnam War formed a toxic brew, shattering America's quarter-century-old strategic consensus over containment. Conservatives began arguing that only cutting back welfare spending and the bureaucracies that administered it could revive economic growth, without which containment would not work, and the Watergate scandal convinced many liberals that they did not hate the Soviets as much as they hated Nixon. With political gridlock paralyzing defense policies, the United States stood by as North Vietnam finally overran the South.

By the late 1970s, the United States was in retreat everywhere. Communists were winning civil wars (and even an election) in Africa and Latin America, as well as hearts and minds in Europe. One Christmasâ1976, I thinkâone of my uncles, an unemployed steelworker, actually gave me a copy of Mao's little red book. In 1979 noncommunist radicals in Iran got in on the game too, hurling the Great Satan out of yet another part of the

inner rim. The final straw came as the year ended, with the Soviets invading Afghanistanâstill the strategic bridge linking heartland and inner rim in South Asia, just as it had been when Russia and Britain had contested it a century earlier.