Village Affairs (7 page)

Authors: Miss Read

'Ain't you got no meth. and newspaper? It does 'em a treat. Keeps the flies off too.'

I said shortly that this was what I used, and that I disliked the smell of methylated spirits.

'My uncle drinks it,' she said cheerfully. 'Gets real high on it. They picks 'im up regular in Caxley, and it's only on meths!' She sounded proud of her uncle's achievements.

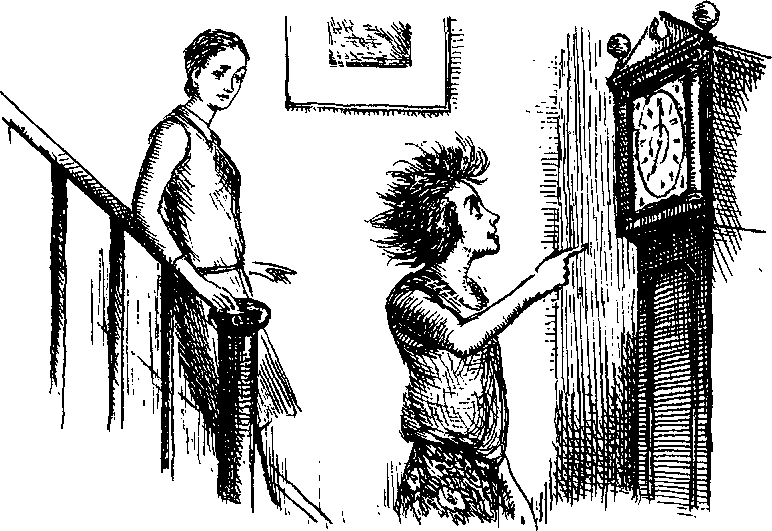

I led the way downstairs.

'You want the grandfather clock done? I could polish up that brass wigger-wagger a treat. And the glass top.'

There was a gleam in her mad blue eye which chilled me.

'Never touch the clock!' I rapped out, in my best schoolmarm voice.

'O.K.' said Minnie, opening the door. 'See you Friday then, if not before.'

I watched her totter on the high heels down the path, still trying to remember where I had seen that skirt before.

'Heaven help us all, Tibby,' I said to the cat, who had wisely absented herself during Minnie's visit. 'Talk about sowing the something-or-other and reaping the whirlwind! I've done just that.'

I felt the need for early bedtime more keenly than ever. Just before I fell asleep, I remembered where I had seen Minnie's skirt before.

It had once been my landing curtain. I must say, it looked better on Minnie than many of her purchases.

Notice of the managers' meeting arrived a few days after Minnie's visit. It was to be held after school as usual, on a Wednesday. There was nothing on the agenda, I observed, about possible closure of the school. Could it be village rumours once again?

The Vicar called at the school on the afternoon following the receipt of our notices. He was in a state of some agitation.

'It's about the managers' meeting. I'm in rather a quandary. My dear wife has inadvertently invited all the sewing ladies that afternoon, so the dining-room will be in use. The table, you know, so convenient for cutting out.'

'Don't worry,' I said. 'We could meet here, if it's easier.'

We usually sit in comfort at the Vicar's mahogany dining-table, under the baleful eye of an ancestor who glares from a massive gilt frame behind the chairman's seat. Sometimes we have met in the drawing-room among the antique glass and the china cabinets.

'And the drawing-room,' went on Mr Partridge, looking anguished, 'is being decorated, and everything is under shroudsâno, not

shrouds

âfurniture coversâno,

loose

coversâno, I don't think that is the correct term eitherâ'

'Dust sheets,' I said.

His face lit up with relief.

'What a

grasp

you have of everthing, dear Miss Read; no wonder the children do so well! Yes, well, you see my difficulty. And my study is so small, and very untidy, I fear. I suppose we could manage something in the hall, but it is rather draughty, and the painters are in and out, you know, about their work, and like to have their little radios going with music, so that I really think it would be

better,

if you are sure it isn't inconveniencingâ'

'Better still,' I broke in, 'have it in my dining-room. There's room for us all.'

'That would be quite perfect,' cried the Vicar, calming down immediately. 'I shall make a note in my diary at once.'

He sighed happily, and made for the door.

'By the way, no more news about the possible closing. Have you heard anything?'

'Not a word.'

'Ah well, no news is good news, they say. We'll hear more perhaps on Wednesday week. I gather that nice Mr Canterbury, who is in charge of the Caxley Office, is coming out himself.'

I thought that sounded ominous but made no comment.

'No,' said the Vicar, clapping a hand to his forehead. 'I don't mean

Canterbury,

do I? Now, what is that fellow's name? I know it's a cathedral city. Winchester? Rochester? Dear, oh dear, I shall forget my own soon.'

'Salisbury,' I said.

'Thank you. I shall put it in my diary against Wednesday week. I shouldn't like to upset such an important fellow.'

He vanished into the lobby.

'It's more likely,' I thought, 'that the important fellow will upset us.'

AMY's last week at Fairacre School arrived all too soon, and I was desolate. She was such good company, as well as being an efficient teacher, that I knew I should miss her horribly.

'Well, I'd stay if I could,' she assured me, 'but Vanessa arrives next week, and I hope she'll stay at least a fortnight. She's rather under the weather. There's a baby on the way.

Or babies,

perhaps!'

'Good heavens! Do they think it will be twins?'

'The foolish girl has been taking some idiotic nonsense called fertility tablets, so it's quite likely she'll give birth to half-a-dozen.'

'But surely, the doctors know what they're doing?'

'Be your age,' said Amy inelegantly. She studied the lipstick with which she had been adorning her mouth. 'I must have had this for years. It's called "Tutankhamen Tint".'

'It can't date from that time.'

Amy sighed.

'The Tutankhamen Exhibition, dear, which dazzled us all some years ago. Everything was Egyptian that year, if you remember. James even bought me a gold necklace shaped like Cleopatra's asp. Devilish cold it is too, coiled on one's nice warm bosom.'

'I'm glad about Vanessa's baby,' I said. 'I'll look forward

to knitting a matinée jacket. I've got a pattern for backward beginners that always turns out well. Is she pleased?'

'After eleven in the morning. Before that, poor darling, she is being sick. Tarquin is terribly thrilled, and already planning a mammoth bonfire for the tenants on the local ben, or whatever North British term they use for a mountain in Scotland.'

'He'll have to build six bonfires if your fears prove correct.'

'He'd be delighted to, I have no doubt. He's a great family man, and I must say he's very, very sweet to Vanessa. They seem extremely happy.'

She snapped shut her powder compact, stood back and surveyed her trim figure reflected murkily in 'The Light of the Word.'

'I think I might present Fairacre School with a pier-glass,' she said thoughtfully.

'It would never get used,' I told her, 'except when you came.'

We went to let in the noisy crowd from the playground.

Mrs Pringle's slimming efforts seemed to be having little result, except to render her even more morose than usual.

I did my best to spare her, exhorting the children to tidy up carefully at the end of afternoon school, and putting away my own things in the cupboards instead of leaving them on window sills and the piano top, as I often do.

Luckily, in the summer term, the stoves do not need attention, but even so, it was obvious that she was finding her work even more martyr-making than before. I was not surprised when she did not appear one morning, soon after Amy's departure, and a note arrived borne by Joseph Coggs.

He pulled it from his trouser pocket in a fine state of stickiness.

I accepted it gingerly.

'How did it get like this, Joe?'

'I gotter toffee in me pocket.'

'What else?'

'I gotter gooseberry.'

'Anything else?'

'I gotter bitter lickrish.'

'You'd better turn out that pocket!'

'I ain't gotterâ'

'And if you say: "I gotter" once more, Joseph Coggs, you'll lose your play.'

'Yes, miss. I was only going to say: "I ain't gotter thing more." He retired to his desk, after putting his belongings on the side table, and I read the missive.

Dear Miss Read,

Have stummuck upset and am obliged to stay home. Have had terrible night, but have taken nutmeg on milk which should do the trick as it has afore.

Clean clorths are in the draw and the head is off of the broom.

Mrs Pringle

I called to see my old sparring partner that evening. She certainly looked unusually pale and listless.

'I'm rough. Very rough,' was her reply to my enquiries. 'And there's no hope of me coming back to that back-breaking job of mine this week.'

'Of course not. We'll manage.'

Mrs Pringle snorted.

'But what I mind more, is not doing out that dining-room of yours for the managers tomorrow.'

'I'll do it. It's not too bad.'

She gave me a dark look.

'I've seen your sort of housework. Dust left on the skirting boards and the top of the doors.'

'I don't suppose any of the managers will be running their fingers along them,' I said mildly. 'Has the doctor been?'

'I'm not calling him in. It's him as started this business.'

'How do you mean.'

'This 'ere diet. Drinking lemon juice first thing in the morning. That's what's made my stummuck flare up.'

'Then leave it off!' I cried. 'Doctor Martin wouldn't expect you to drink it if it upset you!'

'Oh, wouldn't he? And the price of lemons what it is too! I bought a bottle of lemon juice instead. And that's just as bad.'

She waved a hand towards a half empty bottle on the sideboard, and I went to inspect it. It certainly smelled odd.

'Is it fresh?'

Mrs Pringle looked uneasy.

'I bought it half-price in Caxley. The man said they'd had it in some time.'

'Chuck it away,' I said. 'It's off.'

The lady bridled.

'At fifteen pence a bottle? Not likely!'

'Use oranges instead.' I urged. 'This is doing you no good, and anyway oranges are easier to digest.'

She looked at me doubtfully.

'You wouldn't tell Doctor Martin?'

'Of course I wouldn't. Let me empty this down the sink.'

Mrs Pringle sighed.

'Anything you say. I haven't got the strength to argue.'

She watched me as I approached the sink and unscrewed

the bottle. The smell was certainly powerful. The liquid fizzed as it ran down the waste pipe.

'One thing,' she said, brightening, 'it'll clean out the drain lovely.'

It was certainly a pity that Mrs Pringle had not given the dining-room the attention it deserved, but I thought it looked quite grand enough to accommodate the managers.

There are six of them. The Vicar is Chairman and has been for many years, and the next in length of service is the local farmer Mr Roberts.

When I first was appointed I was interviewed by Colonel Wesley and Miss Parr, both then nearing eighty, and now at rest in the neighbouring churchyard. Their places were taken by Mrs Lamb, the wife of the postmaster, and Peter Hale, a retired schoolmaster from Caxley, who is very highly regarded by the inhabitants of Fairacre and brings plenty of common sense and practical experience of schooling to the job.

The other two managers are Mrs Mawne and Mrs Moffat, the latter the sensible mother of Linda Moffat, the best dressed child in the school. She is particularly valuable, as she can put forward the point of view of parents generally, and is not too shy to speak her mind.

On Wednesday we had a full house, which is unusual. It is often Mr Roberts who is unable to be present and who sends a messageâor sometimes puts an apologetic face round the doorâto say a ewe or cow is giving birth, or the harvest is at a crucial stage, and quite rightly we realise the necessity for putting first things first, and the meeting proceeds without him.

As well as the six managers Mr Salisbury arrived complete with pad for taking notes. I had a seat by him, with my usual brief report on such school matters as attendance, social activities and the like. Also in evidence were the log book of the school and the punishment bookâthe latter with its pages virtually unsullied since my advent.

The Vicar made a polite little speech about the pleasure of using my house for the meeting. The minutes were ready and signed and I gave my report.

There were the usual requests to the office for more up-to-date lavatories and wash-basins. The skylight, which has defied generations of Fairacre's handy men to render it rain-proof, was mentioned once more, and Mr Salisbury solemnly made notes on the pad. We fixed a date for our next term's meeting, and then settled back for Any Other Business.

'Is there any message, in particular,' asked Gerald Partridge, 'from the office? We have heard some disquieting rumours.'

'Oh?' said Mr Salisbury. 'What about?'

'Might close the school' said Mr Roberts, who does not mince words.

'Really?'

cried Mrs Moffatt. 'I hadn't heard a thing! Now that I get my groceries delivered I hardly ever go to the shop, and it's amazing how little one hears.'

'I've taken to going into Caxley for my provisions' said Mrs Mawne conversationally. 'I can't say I enjoy these supermarkets, but when soap powder is ten pence cheaper it makes you think.'

'And bleaching liquid,' agreed Mrs Moffatt, 'and things like tomato ketchup.'

'I make my own,' broke in Mrs Lamb. 'We grow more tomatoes than we can cope with, and it's no good trying to freeze them, and bottled tomatoes are not the same as fresh

ones, are they? If you are interested, I've a very good recipe for ketchup I can let you have.'

The ladies accepted the offer enthusiastically. The Vicar wore his resigned look. Most of our village meetings get out of hand like this, and he is quite used to waiting for these little asides to resolve themselves.