Village Affairs (3 page)

Authors: Miss Read

'Horrible! But it's common knowledge that they go on growing after death.'

'A solemn thought, to imagine all those dark partings on Judgement Day,' commented Amy, patting her own neat waves. 'Well, what's the Fairacre news?'

I told her about the school, and its possible closure.

'That's old hat. I shouldn't worry unduly about that, though I did hear someone saying they'd heard that Beech Green was to be enlarged.'

'The grape vine spreads far and wide,' I agreed.

'But what about Mrs Fowler?'

'Mrs Fowler?' I repeated with bewilderment. 'You mean that wicked old harridan who used to live in Tyler's Row? Why, she left for Caxley years ago!'

'I know she did. That's why I hear about her from my window cleaner who lives next door to her, poor fellow. Well, she's being courted.'

'Never! I don't believe it!'

Amy looked pleasantly gratified at my reactions.

'And what's more, the man is the one that Minnie Pringle married.'

This was staggering news, and I was suitably impressed. Minnie Pringle is the niece of my redoubtable Mrs Pringle. We Fairacre folk have lost count of the children she has had out of wedlock, and were all dumb-founded when we heard that she was marrying a middle-aged man with children of his own. As far as I knew, they had settled down fairly well together at Springbourne. But if Amy's tale were to be believed, then the marriage must be decidedly shaky.

'Mrs Pringle hasn't said anything,' I said.

'She may not know anything about it.'

'Besides,' I went on, 'can you imagine anyone falling for Mrs Fowler? She's absolutely without charms of any sort.'

'That's nothing to do with it,' replied Amy. 'There's such a thing as incomprehensible attraction. Look at some of the truly dreadful girls at Cambridge who managed to snaffle some of the most attractive men!'

'But Mrs Fowlerâ' I protested.

Amy swept on.

'One of the nastiest men I ever met,' she told me, 'had four wives.'

'What? All at once? A Moslem or something?'

'No, no,' said Amy testily. 'Don't be so headlong!'

'You mean headstrong.'

'I know what I mean, thank you. You rush

headlong

to conclusions, is what I mean.'

'I'm sorry. Well, what was wrong with this nasty man you knew?'

'For one thing, he cleaned out his ears with a match stick.'

'Not the striking end, I hope. It's terribly poisonous.'

'

Whichever

end he used, the operation was revolting.'

'Oh, I agree. Absolutely. What else?'

'Several things. He was mean with money. Kicked the cat. Had Wagnerâof all peopleâtoo loud on the gramophone. And yet, you see, he had this charm, this charismaâ'

'Now there's a word I never say! Like "Charivari". "punch or the London" one, you know.'

Amy tut-tutted with exasperation.

'The point I have been trying to make for the last ten minutes,' shouted Amy rudely, '

against fearful odds

, is that Minnie Pringle's husband must see something attractive in Mrs Fowler.'

'I thought we'd agreed on that: I said. 'More coffee?'

'Thank you,' said Amy faintly. 'I feel I need it.'

The fascinating subject of Mrs Fowler and her admirer did not crop up again until the last day of the spring term.

Excitement, as always, was at fever-pitch among the children. One would think that they were endlessly beaten and bullied at school when one sees the joy with which they welcome the holidays.

Pat Smith, who had been my infants' teacher for the past two years, was leaving to get married at Easter, and we presented her with a tray, and a large greetings card signed by all the children.

The Vicar called to wish her well, and to exhort the children to help their mothers during the holidays, and to enjoy themselves.

When he had gone, I contented myself with impressing upon them the date of their return, and let them loose. Within minutes, the stampede had vanished round the bend of the lane, and I was alone in the schoolroom.

I always love that first moment of solitude, when the sound of the birds is suddenly noticed, and the scent of the flowers reminds one of the quiet country pleasures ahead. Now, freed from the bondage of the clock and the school timetable, there would be time 'to stand and stare', to listen to the twittering of nestlings, the hum of the early foraging bees, and the first sound of the cuckoo from the coppice across the fields.

Spring is the loveliest time of the year at Fairacre, when everything is young, and green, and alive with hope. Soon the house martins would be back, and the swifts, screaming round and round the village as they selected nesting places. Then the swallows would arrive, seeking out their old familiar hauntsâMr Roberts' barn rafters, the Post Office porch, the loft above the Vicar's stablesâin which to build their nests.

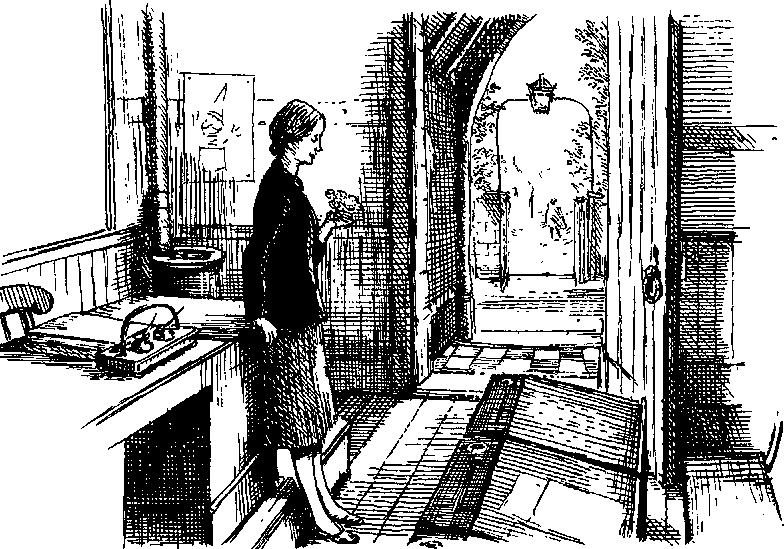

Someone had brought me a bunch of primroses as an end of term present. Holding the fragrant nosegay carefully, I made my way through the school lobby towards my home across the playground, full of anticipation at the happiness ahead.

The door scraper clanged. The door opened, and Mrs Pringle, her mouth set grimly, confronted me.

'Sorry I'm a few minutes late,' she began, 'but I'm In Trouble.'

In Fairacre, this expression is commonly used to describe pregnancy, but in view of Mrs Pringle's age, I rightly assumed that she used the term more generally.

'What's wrong?'

'It's our Minnie,' said Mrs Pringle. 'Up my place. In a fair taking, she is. Can't do nothing with her. I've left her crying her eyes out.'

'Oh, dear,' I said weakly, my heart sinking. Could Amy have heard aright?

I smelt my sweet primroses to give me comfort.

'Come to the house and sit down,' I said.

Mrs Pringle raised a hand, and shook her head.

'No. I've come to work, and work I will!'

'Well, at least sit on the bench while you tell me.'

A rough plank bench in the playground, made by Mr Willet, acts as seat, vaulting horse, balancing frame and various other things, and on this we now rested, Mrs Pringle with her black oilcloth bag on her lap, and the primroses on mine. In the hedge dividing the playground from the lane, a blackbird scolded as Tibby, my cat, emerged from the school house to see why I was taking so long to get into the kitchen to provide her meal.

'That man,' said Mrs Pringle, 'has up and left our Minnie. What's more, he's left his kids, and hers, and that one of theirs, to look after, while he gallivants with that woman who's no better than she should be.'

'Perhaps he'll come back,' I suggested.

'Not him! He's gone for good. And d'you know who he's with?'

'No,' I said, expecting to be struck by lightning for downright lying.

'You'll never guess. That Mrs Fowler from Tyler's Row.'

I gave a creditable gasp of surprise.

'The scheming hussy,' said Mrs Pringle wrathfully. A wave of scarlet colour swept up her neck and into her cheeks, which were awobble with indignation.

'It's my belief she knew he had an insurance policy coming out this month. After his money, you see. Well, it wouldn't have been his looks, would it?'

I was obliged to agree, but remembered Amy's remark about the plain girls and the young Adonises at Cambridge. Who could tell?

'But, top and bottom of it all isâhow's Minnie to live? Oh, I expect she'll get the Social Security and Family Allowance, and all that, but she'll need a bit of work as well, I reckons, if she's to keep that house on at Springbourne.'

'Won't he provide some money?'

'That'll be the day,' said Mrs Pringle sardonically. 'Unless Min takes him to court, and who's got the time and money to bother with all that?'

Mrs Pringle's view of British justice was much the same as her views of my housekeeping, it seemed, leaving much to be desired.

'If she really needs work,' I said reluctantly, 'I could give her half a day here cleaning silver, and windows, and things.'

Mrs Pringle's countenance betrayed many conflicting emotions. Weren't her own ministrations on my behalf enough then? And what sort of a hash would Minnie make of any job offered her? And finally, it was a noble gesture to offer her work anyway.

Luckily, the last emotion held sway.

'That's a very kind thought, Miss Read. Very kind indeed.'

She struggled to her feet, and we stood facing each other. Tibby began to weave between our legs, reminding us of her hunger.

"But let's hope it won't come to that,' she said. I hoped so too, already regretting my offer.

Mrs Pringle turned towards the lobby door.

'I'll let you know what happens,' she said, 'but I'll get on with a bit of scrubbing now. Takes your mind off things, a bit of scrubbing does.'

She stumped off, black bag swinging, whilst Tibby and I made our way home.

THE policeman from Caxley, who had called upon the Coggs' household, was making enquiries, we learnt, about the theft of lead in the neighbourhood.

Scarcely a week went by but

The Caxley Chronicle

reported the stripping of lead from local roofs around the Caxley area. Many a beautiful lead figure too, which had graced a Caxley garden for generations, was spirited away under cover of darkness, lead water tanks and cisterns, lead guttering, lead piping, all fell victim to a cunning band of thieves who knew just where to collect this valuable metal.

It so happened that the Mawnes had an ancient summer house, with a lead roof, in their garden.

Their house had been built in the reign of Queen Anne, and the octagonal summer house, according to Mr Willet, who considered it unsafe and unnecessarily ornate, was erected not long afterwards, although it was, more likely, the conceit of some Victorian architect. It was hidden from the house by a shrubbery, and nothing could have been easier for thieves than to slip through the hedge from the fields adjoining the garden and to do their work in privacy.

The lead was not missed until a thundery shower sent cascades of water through the now unprotected roof into the little room below. A wicker chair and its cushion were drenched, a water colour scene, executed by Mrs Mawne in

her youth, became more water than colour overnight, and a rug, which Mr Mawne had brought back from Egypt on one of his bird-watching trips, and which he much prized, was quite ruined. Added to all this was the truly dreadful smell composed of wet timber and the decaying bodies of innumerable insects, mice, shrews and so on, washed from their resting places by the onrush of rain.

Fairacre was shocked at the news. It was one thing to read about lead being stolen from villages a comfortable distance from their own, in the pages of the respected

Caxley Chronicle.

It was quite another to find that someone had actually been at work in Fairacre itself. What would happen next?

Mr Willet voiced the fears of his neighbours as he returned from choir practice one Friday night.

'What's to stop them blighters pinching the new lead off of the church roof? Cost a mint of money to put on. It'd make a fine haul for some of these robbers.'

A violent storm, some years earlier, had damaged St Patrick's sorely. Only by dint of outstanding efforts on the part of the villagers, and never-to-be-forgotten generosity from American friends of Fairacre, had the necessary repairs been made possible. The sheets of lead, then fixed upon much of the roof had formed one of the costliest items in the bill. No wonder Fairacre folk feared for its safety, now that marauders had visited their village.

'They wouldn't dare to take the Lord's property,' announced Mrs Pringle.

'I don't think they care much whose property it is,' observed Mr Lamb from the Post Office. 'It's just how easy they can turn it into hard cash,'

'My sister in Caxley' replied Mrs Pringle, still seeking the lime-light, 'told me the most shocking thing happened all up the road next to hers.'

'What?' asked Mr Willet. The party had reached the Post Office by now, and stopped to continue the conversation before Mr Lamb left them.

Twilight was beginning to fall. The air was still and scented with the flowers in cottage gardens.

Mrs Pringle looked up and down the road before replying. Her voice was low and conspiratorial. Mr Willet and Mr Lamb bent their heads to hear the disclosure.

'Well, these lead thieves came one night and went along all the outside lavatories, and cut out every bit of piping from the cistern to the pan.'

'No!'

'They did. As true as I'm standing here!'

'What! Every house?'

Mrs Pringle shifted her chins uncomfortably upon the neck of her cardigan.

'Not quite all. Mr Jarvis, him what was once usher at the Court, happened to be in his when they reached it, so they cleared off pretty smartly.'

'Did they catch 'em?'

'Not one of 'em!' pronounced Mrs Pringle. 'Still at large, they are. Quite likely the very same as took Mr Mawne's lead off the summer house.'

'Could be,' agreed Mr Lamb, making towards his house now that the story was done. 'Though I heard as Arthur Coggs might be mixed up with this little lot.'