Vertigo (8 page)

Authors: W. G. Sebald,Michael Hulse

Tags: #Classics, #Contemporary, #Travel, #Writing

open eyes of the knight, already wandering sideways to the hard and bloody battle ahead, against the self-contained expression of the woman indicated by little more than a slight

lowering of her gaze. On the third day of my stay in Verona, I took my evening meal in a pizzeria in the Via Roma. I do not know how I go about choosing the restaurants where I eat in unfamiliar cities. On the one hand I am too fastidious and wander the streets broad and narrow for hours on end before I make up my mind; on the other hand I generally finish up turning in simply anywhere, and then, in dreary surroundings and with a sense of discontent, select some dish that does not in the least appeal. That was how it was on that evening of the 5th of November. If I had heeded my first inclination, I would never have crossed the threshold of that establishment, which even from the outside made a disreputable impression. But now there I sat, on a kitchen chair with a cover of red marbled plastic, at a rickety table, in a grotto festooned with fishing nets. The decor of the floor and walls was a hideous marine blue which put an end to all hope I might have entertained of ever seeing dry land again. The sense of being wholly surrounded by water was rendered complete by a sea piece that hung right below the ceiling opposite me, in a frame painted a golden bronze. As is commonly the case with such sea pieces, it showed a ship, on the crest of a turquoise wave crowned with snow-white foam, about to plunge into the yawning depths that gaped beneath her bows. Plainly this was the moment immediately before a disaster. A mounting sense of unease took possession of me. I was obliged to push aside the plate, barely half of the pizza eaten, and grip the table edge, as a seasick man might grip a ship's rail. I sensed my brow running cold with fear, but was quite unable to call the waiter over and ask for the bill. Instead, in order to focus on reality once more, I pulled the newspaper I had bought that afternoon, the Venice

Gazzettino

, out of my jacket pocket and unfolded it on the table as best I could. The first article that caught my attention was an editorial report to

the effect that yesterday, the 4th of November, a letter in strange runic writing had been received by the newspaper, in which a hitherto unknown group by the name of

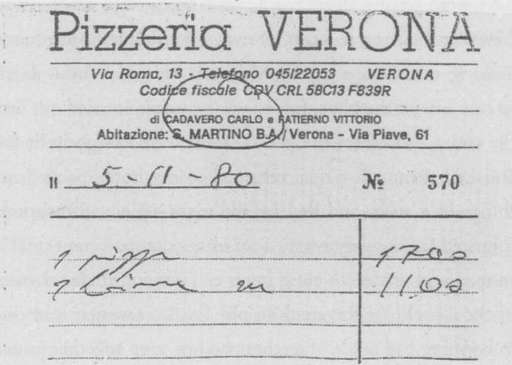

claimed responsibility for a number of murders that had been committed in Verona and other northern Italian cities since 1977. The article brought these as yet unsolved cases back to the memories of its readers. In late August 1977, a romany named Guerrino Spinelli had died in a Verona hospital of severe burns sustained when the old Alfa in which he customarily spent the night on the outskirts of the city was set on fire by persons unknown. A good year later, a waiter, Luciano Stefanato, was found dead in Padua with two 25-centimetre stab wounds in the neck, and another year after that a 22-year-old heroin addict, Claudio Costa, was found dead with thirty-nine knife wounds. It was now the late autumn of 1980. The waiter brought me the bill. It was folded and I opened it out. The letters and numbers blurred before my eyes.

The 5th of November, 1980. Via Roma. Pizzeria Verona. Di Cadavero Carlo e Patierno Vittorio.

Patierno and Cadavero. -

The telephone rang. The waiter wiped a glass dry and held it up to the light. Not until I felt I could stand the ringing no longer did he pick up the receiver. Then, jamming it between his shoulder and his chin, he paced to and fro behind the bar as far as the cable would let him. Only when he was speaking himself did he stop, and at these times he would lift his eyes to the ceiling. No, he said, Vittorio wasn't there. He was hunting. Yes, that was right, it was him, Carlo. Who else would it be? Who else would be in the restaurant? No, nobody. Not a soul all day. And now there was only one diner.

Un inglese,

he said, and looked across at me with what I took to be a touch of contempt. No wonder, he said, the days were getting shorter. The lean times were on the way.

L'inverno è alle porte. si, si, l'inverno,

he shouted once more, looking over at me again. My heart missed a beat. I left 10,000 lire on the plate, folded up the paper, hurried out into the street and across the piazza, went into a brightly lit bar and had them call a taxi, returned to my hotel, packed my things in a rush, and fled by the night train to Innsbruck. Prepared for the very worst, I sat in my compartment unable to read and unable to close my eyes, listening to the rhythm of the wheels. At Rovereto an old Tyrolean woman carrying a shopping bag made of leather patches sewn together joined me, accompanied by her son, who might have been forty. I was immeasurably grateful to them when they came in and sat down. The son leaned his head back against the seat. Eyelids lowered, he smiled blissfully most of the time. At intervals, though, he would be seized by a spasm, and his mother would then make signs in the palm of his left hand, which lay in her lap, open, like an unwritten page. The train hauled onwards, uphill. Gradually I began to feel better. I went out into the corridor. We were in Bolzano. The Tyrolean woman and her son got out. Hand in hand the two of them headed towards the underpass. Even before they had vanished from sight, the train started off again. It was now beginning to feel distinctly colder. The train moved more slowly, there were fewer lights, and the darkness was thicker. Franzensfeste station passed. I saw scenes of a bygone war: the assault on the pass - Vall'Inferno - the 26th of May, 1915. Bursts of gunfire in the mountains and a forest shot to shreds. Rain hatched the window-panes. The train changed track at points. The pallid glow of arc-lamps suffused the compartment. We stopped at the Brenner. No one got out and no one got in. The frontier guards in their grey greatcoats paced to and fro on the platform. We remained there for at least a quarter of an hour. Across on the other side were the silver ribbons of the rails. The rain turned to snow. And a heavy silence lay upon the place, broken only by the bellowing of some nameless animals waiting in a siding to be transported onwards.

In the summer of 1987, seven years after I fled from Verona, I finally yielded to a need I had felt for some time to repeat the journey from Vienna via Venice to Verona, in order to probe my somewhat imprecise recollections of those fraught and hazardous days and perhaps record some of them. On this occasion in the midst of the holiday season, the night train from Vienna to Venice, on which in the late October of 1980 I had seen nobody except a pale-faced schoolmistress from New Zealand, was so overcrowded that I had to stand in the corridor all the way or crouch uncomfortably among suitcases and rucksacks, so that instead of drifting into sleep I slid into my memories. Or rather, the memories (at least so it seemed to me) rose higher and higher in some space outside of myself, until, having reached a certain level, they overflowed from that space into me, like water over the top of a weir. Once I had begun to write, the time passed more swiftly than I should ever have thought possible, and it was not until the train was rolling slowly from Mestre over the railway causeway, crossing the lagoon which stretched out on either side in the gleam of the night, that I came to. At Santa Lucia I was one of the last to get out. With my blue canvas bag slung as ever across my shoulder, I slowly walked down the platform to the station hall, where a veritable army of backpackers were lying on the stone floor in sleeping-bags on straw mats, close to each other like an alien people resting on their way through the desert. Out in the station forecourt, too, countless young men and women lay in groups or couples or singly, on the steps and all around. I sat on the Riva and took out my writing materials, the pencil and the fine-ruled paper. The red glow of dawn was already breaking over the eastward roofs and domes of the city. Here and there, sleepers stirred in the no man’s land where they had spent the night, propped themselves up and began to rummage through their belongings, eating a bite or drinking a little and then stowing it all carefully away again. Presently, bowed under heavy packs, which reached a full head above them, several began moving among their brothers and sisters still lying on the ground, as if they were preparing for the next stage of an arduous and never-ending journey.

I sat on the Fondamenta Santa Lucia until half the morning was gone. The pencil flew across the paper, and from time to time a cockerel crowed from its cage on the balcony of a house across the canal. When I looked up once again from my work, the shadowy forms of the sleepers on the station forecourt had all vanished, or had faded away, and the morning traffic had begun. At one point a barge laden with heaps of rubbish came by. A large rat scuttled along its gunnel and, having reached the bow, plunged head first into the water. I cannot say whether it was the sight of this that made me decide not to stay in Venice but to travel on to Padua instead, without delay, and seek out Enrico Scrovegni's Arena Chapel. Hitherto all I knew of it was an account that described the undiminished intensity of the colours in Giotto's frescoes, and the certainty which governs every stride and feature of the figures represented. Once I entered the chapel, from the heat that already prevailed in the city even in the early morning of that day, and stood before the three rows of frescoes that cover the walls up to the ceiling, I was overwhelmed by the silent lament of the angels, who have kept their station above our endless calamities for nigh on seven centuries. Their lament resounded in the very silence of the chapel and their eyebrows were drawn so far together in their grief that one might have supposed them blindfolded. And are not their white wings, I thought, with those few