Vertigo (6 page)

Authors: W. G. Sebald,Michael Hulse

Tags: #Classics, #Contemporary, #Travel, #Writing

When the train had arrived in Venice, I first went to the station barber's for a shave, and then stepped out into the forecourt of Ferrovia Santa Lucia. The dampness of the autumn morning still hung thick among the houses and over the Grand Canal. Heavily laden, the boats went by, sitting low in the water. With a surging rush they came from out of the mist, pushing ahead of them the aspic-green waves, and disappearing again in the white swathes of the air. The helmsmen stood erect and motionless at the stern. Their hands on the tiller, they gazed fixedly ahead. I walked from the Fondamenta across the broad square, up Rio Terrà Lista di Spagna and across the Canale di Cannaregio. As you enter into the heart of that city, you cannot tell what you will see next or indeed who will see you the very next moment. Scarcely has someone made an appearance than he has quit the stage again by another exit. These brief exhibitions are of an almost theatrical obscenity and at the same time have an air of conspiracy about them, into which one is drawn against one's will. If you walk behind someone in a deserted alleyway, you have only to quicken your step slightly to instill a little fear into the person you are following. And equally, you can feel like a quarry yourself. Confusion and ice-cold terror alternate. It was with a certain feeling of liberation, therefore, that I came upon the Grand Canal once again, near San Marcuola, after wandering about for the best part of an hour below the tall houses of the ghetto. Hurriedly, like the native Venetians on their way to work, I boarded a vaporetto. The mist had now dispersed. Not far from me, on one of the rear benches, there sat, and in fact very nearly lay, a man in a worn green loden coat whom I immediately recognised as King Ludwig II of Bavaria. He had grown somewhat older and rather gaunt, and curiously he was talking to a dwarfish lady in the strongly nasal English of the upper classes, but otherwise everything about him was right: the sickly pallor of the face, the wide-open childlike eyes, the wavy hair, the carious teeth. Il re Lodovico to the life. In all likelihood, I thought to myself, he had come by water to the

città inquinata Venezia merda.

After we had alighted I watched him walk away down the Riva degli Schiavoni in his billowing Tyrolean cloak, becoming smaller and smaller not only on account of the increasing distance but also because, as he went on talking incessantly, he bent down deeper and deeper to his diminutive companion. I did not follow them, but instead took my morning coffee in one of the bars on the Riva, reading the

Gazzettino

, making notes for a treatise on King Ludwig in Venice, and leafing through Grillparzer's

Italian Diary,

written in 1819. I had bought it in Vienna, because when I am travelling I often feel as Grillparzer did on his journeys. Nothing pleases me, any more than it did him; the sights I find infinitely disappointing, one and all; and I sometimes think that I would have done far better to stay at home with my maps and timetables. Grillparzer paid even the Doge's Palace no more than a distinctly grudging respect. Despite its delicately crafted arcades and turrets, he wrote, the Doge's palace was inelegant and reminded him of a crocodile. What put this comparison into his head he did not know. The resolutions passed here by the Council of State must surely be mysterious, immutable and harsh, he observed, calling the palace an enigma in stone. The nature of that enigma was apparently dread, and for as long as he was in Venice Grillparzer could not shake off a sense of the uncanny. Trained in the law himself, he dwelt on that palace where the legal authorities resided and in the inmost cavern of which, as he put it, the Invisible Principle brooded. And those who had faded away, the persecutors and the persecuted, the murderers and the victims, rose up before him with their heads enshrouded. Shivers of fever beset the poor hypersensitive man.

One of the victims of Venetian justice was Giacomo Casanova. His

Histoire de mafuite des prisons de la République de Venise qu'on appelle Les Plombs écrite a Dux en Bohème l'année 1787,

first published in Prague in 1788, affords an excellent insight into the inventiveness of penal justice at the time. For example, Casanova describes a type of garrotte. The victim is positioned with his back to a wall on which a horseshoe-shaped brace is mounted, and his head is jammed into this brace in such a way that it half encloses the neck. A silken band is passed around the neck and secured to a spool which a henchman turns slowly till at length the last throes of the condemned man are over. This strangulating apparatus is in the prison chambers below the lead roofs of the Doge's Palace. Casanova was in his thirtieth year when he was taken there. On the morning of the 26th of July, 1755, the Messergrande entered his room. Casanova was ordered to surrender any writings by himself or others that he possessed, to get dressed and to follow the Messergrande. The word "tribunal", he writes, completely paralysed me and left me only such physical strength as was essential if I were to obey. Mechanically he performed his ablutions and donned his best shirt and a new coat that had only just left the tailor's hands, as if he were off to a wedding. Shortly after he found himself in the loft space of the palace, in a cell measuring twelve feet by twelve. The ceiling was so low that he could not stand, and there was not a stick of furniture. A plank no more than a foot wide was fixed to the wall, to serve as both table and bed, and on it he laid his elegant silk mantle, the coat, inaugurated on so inauspicious an occasion, and his hat adorned with Spanish lace and an egret's plume. The heat was appalling. Through the bars, Casanova could see rats as big as hares scuttling about. He crossed to the window sill, from which he could see but a patch of sky. There he remained motionless for a full eight hours. Never in his life, he recorded, had the taste in his mouth been as bitter. Melancholy had him in its grip and would not let go. The dog days came. The sweat ran down him. For two weeks he did not move his bowels. When at last the stone-hard excrement was passed, he thought the pain would kill him. Casanova considered the limits of human reason. He established that, while it might be rare for a man to be driven insane, little was required to tip the balance. All that was needed was a slight shift, and nothing would be as it formerly was. In these deliberations, Casanova likened a lucid mind to a glass, which does not break of its own accord. Yet how easily it is shattered. One wrong move is all that it takes. This being so, he resolved to regain his composure and find a way of comprehending his situation. It was soon apparent that the condemned in that gaol were honourable persons to a man, but for reasons which were known only to their Excellencies, and were not disclosed to the detainees, they had had to be removed from society. When the tribunal seized a criminal, it was already convinced of his guilt. After all, the rules by which the tribunal proceeded were underwritten by senators elected from among the most capable and virtuous of men. Casanova realised that he would have to come to terms with the fact that the standards which now applied were those of the legal system of the Republic rather than of his own sense of justice. Fantasies of revenge of the kind he had entertained in the early days of his detention - such as rousing the people and, with himself at their head, slaughtering the government and the aristocracy - were out of the question. Soon he was prepared to forgive the injustice done to him, always providing he would some day be released. He found that, within certain limits, he was able to reach an accommodation with the powers who had confined him in that place. Everyday necessities, food and a few books were brought to his cell, at his own expense. In early November the great earthquake hit Lisbon, raising tidal waves as far away as Holland. One of the sturdiest roof joists visible through the window of Casanova's gaol began to turn, only to move back to its former position. After this, with no means of knowing whether his sentence might not be life, he abandoned all hope of release. All his thinking was now directed to preparing his escape from prison, and this occupied him for a full year. He was now permitted to take a daily walk around the attics, where a good deal of lumber lay about, and contrived to obtain a number of things that could serve his purpose. He came across piles of old ledgers with records of trials held in the previous century. They contained charges brought against confessors who had extorted penances for improper ends of their own, described in detail the habits of schoolmasters convicted of pederasty, and were full of the most extraordinary accounts of transgressions, evidently detailed for the delectation solely of the legal profession. Casanova observed that one kind of case that occurred with particular frequency in those old pages concerned the deflowering of virgins in the city's orphanages, among them the very one whose young ladies were heard every day in Santa Maria della Visitazione, on the Riva degli Schiavoni, uplifting their voices to the ceiling fresco of the three cardinal virtues, to which Tiepolo had put the finishing touches shortly after Casanova was arrested. No doubt the dispensation of justice in those days, as also in later times, was largely concerned with regulating the libidinous instinct, and presumably not a few of the prisoners slowly perishing beneath the leaden roof of the palace will have been of that irrepressible species whose desires drive them on, time after time, to the very same point.

In the autumn of his second year of imprisonment, Casanova's preparations had reached the stage at which he could contemplate an escape. The moment was propitious, since the inquisitors were to cross to the

terra firma

at that time, and Lorenzo, the warder, always got drunk when his superiors were away. In order to decide on the precise day and hour, Casanova consulted Ariosto's

Orlando Furioso,

using a system comparable to the

Sortes Virgilianae.

First he wrote down his question, then he derived numbers from the words and arranged these in an inverse pyramid, and finally, in a threefold procedure that involved subtracting nine from every pair of figures, he arrived at the first line of the seventh stanza of the ninth canto of

Orlando Furioso,

which runs:

Tra il fin d'ottobre e il capo di novembre.

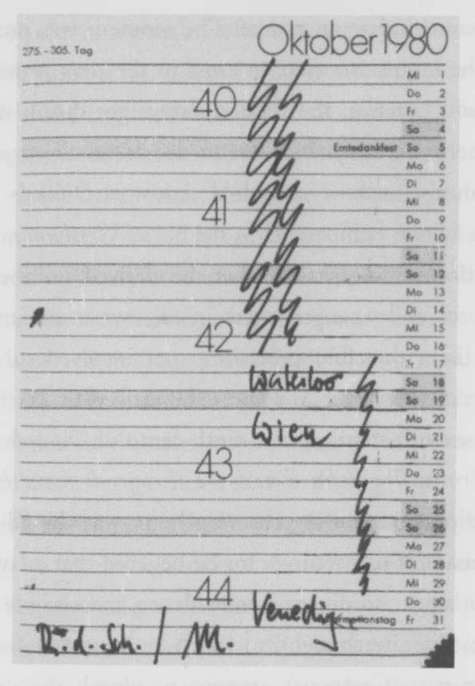

This instruction, pinpointing the very hour, was the all-decisive sign Casanova had wanted, for he believed that a law was at work in so extraordinary a coincidence, inaccessible to even the most incisive thought, to which he must therefore defer. For my part, Casanova's attempt to plumb the unknown by means of a seemingly random operation of words and numbers later caused me to leaf back through my own diary for that year, whereupon I discovered to my amazement, and indeed to my considerable alarm, that the day in 1980 on which I was reading Grillparzer's journal in a bar on the Riva degli Schiavoni between the Danieli and Santa Maria della Visitazione, in other words near the Doge's Palace, was

the very last day of October, and thus the anniversary of the day (or rather, night) on which Casanova, with the words

E quindi uscimmo a rimirar le stelle

on his lips, broke out of the lead-plated crocodile. Later that evening I returned to the bar on the Riva and fell into conversation with a Venetian by the name of Malachio, who had studied astrophysics at Cambridge and, as shortly transpired, saw everything from a great distance, not only the stars. Towards midnight we took his boat, which was moored outside, up the dragon's tail of the Grand Canal, past the Ferrovia and the Tronchetto, and out onto the open water, from where one has a view of the lights of the Mestre refineries stretching for miles along the coast. Malachio turned off the engine. The boat rose and fell with the waves, and it seemed to me that a long time passed. Before us lay the fading lustre of our world, at which we never tire of looking, as though it were a celestial city. The miracle of life born of carbon, I heard Malachio say, going up in flames. The engine started up once more, the bow of the boat lifted in the water, and we entered the Canale della Giudecca in a wide arc. Without a word, my guide pointed out the Inceneritore Comunale on the nameless island westward of the Giudecca. A deathly silent concrete shell beneath a white pall of smoke. I asked whether the burning went on throughout the night, and Malachio replied:

Si, di continuo. Brucia continuamente.

The fires never go out. The Stucky flour mill entered our line of vision, built in the nineteenth century from millions of bricks, its blind windows staring across from the Giudecca to the Stazione Marittima. The structure is so enormous that the Doge's Palace would fit into it many times over, which leaves one wondering if it was really only grain that was milled in there. As we were passing by the facade, looming above us in the dark, the moon came out from behind the clouds and struck a gleam from the golden mosaic under the left gable, which shows the female figure of a reaper holding a sheaf of wheat, a most disconcerting image in this landscape of water and stone. Malachio told me that he had been giving a great deal of thought to the resurrection, and was pondering what the Book of Ezekiel could mean by saying that our bones and flesh would be carried into the domain of the prophet. He had no answers, but believed the questions were quite sufficient for him. The flour mill dissolved into the darkness, and ahead of us appeared the tower of San Giorgio and the dome of Santa Maria della Salute. Malachio steered the boat back to my hotel. There was nothing more to be said. The boat docked. We shook hands. I stepped ashore. The waves slapped against the stones, which were overgrown with shaggy moss. The boat turned about in the water. Malachio waved one more time and called out:

Ci vediamo a Gerusalemme.

And, a little further out, he repeated somewhat louder: Next year in Jerusalem! I crossed the forecourt of the hotel. There was not a soul about. Even the night porter had abandoned his post and was lying on a narrow bed in a kind of doorless den behind the reception desk, looking as if his body had been laid out. The test card was flickering softly on the television.

Machines alone have realised that sleep is no longer permitted, I thought as I ascended to my room, where tiredness soon overcame me too.