Vertigo (13 page)

Authors: W. G. Sebald,Michael Hulse

Tags: #Classics, #Contemporary, #Travel, #Writing

however, I added an urgent request to photograph the flock of pigeons that had just flown from the piazza into the Via Roma, and had settled on the balcony rail and the roof of the building, the young Erlanger, who, as I now thought, might have been on honeymoon, was not prepared to oblige me a second time, probably, I suspected, because his newly-wed bride, who had been eyeing me the whole time with a distrusting and even hostile air and had not budged from his side even when he was taking the picture, was plucking impatiently at his sleeve.

When I arrived at the piazza, Salvatore was already sitting reading outside the bar with the green awning, his glasses pushed up onto his forehead and holding the book so close to his face that it was quite impossible to believe he could decipher anything at all. Taking care not to disturb him, I sat down. The book he was reading had a pink dust jacket bearing the portrait of a woman, in dark colours. Below the portrait, in lieu of a title, were the numbers

ipi2+i.

A waiter came to the table. He was wearing a long green apron. I ordered a double Fernet on the rocks. Salvatore had meanwhile laid his book aside and restored his glasses to their proper place. He explained apologetically that in the early evening when he had at last escaped the pressures of the daily round he would always turn to a book, even if he had left his reading glasses in the office, as he had today. Once I am at leisure, said Salvatore, I take refuge in prose as one might in a boat. All day long I am surrounded by the clamour on the editorial floor, but in the evening I cross over to an island, and every time, the moment I read the first sentences, it is as if I were rowing far out on the water. It is thanks to my evening reading alone that I am still more or less sane. He was sorry he had not noticed me right away, he said, but being short-sighted and also absorbed in Sciascias story had cut him off almost completely from what was going on around him. The story Sciascia was telling, he continued, as it were returning to the real world, was a fascinating synopsis of the years immediately before the First World War. At the centre of the narrative, which was more like an essay in form, was one Maria Oggioni

nata

Tiepolo, wife of a Capitano Ferrucio Oggioni, who on the 8th of November, 1912, shot her husband's batman, a

bersagliere

by the name of Quintilio Polimanti, in self-defence according to her own statement. At the time the newspapers naturally made a meal of the story, and the trial, which gripped the nation's imagination for weeks - since after all the accused was of the famous Venetian painter's family, as the press tirelessly repeated - this trial, which kept the entire nation on the edge of its seat, finally revealed no more than a truth familiar to everyone: that the law is not equal for all, and justice not just. Since Polimanti was no longer able to speak for himself, Signora Oggioni, whom everyone was soon calling Contessa Tiepolo, found it easy to win over the judges with that enigmatic smile of hers, a smile that promptly reminded journalists of the Mona Lisa's, as one can imagine, the more so since in 1913 La Gioconda was also in the headlines, having been discovered under the bed of a Florentine workman who had liberated her from her exile in the Louvre two years before and returned her to her native country. It is curious to observe, added Salvatore, how in that year everything was moving towards a single point, at which something would have to happen, whatever the cost. But you, he went on, were interested in a quite different story. And that story, to tell you the end of it first, has now almost reached its conclusion. The trial has been held. The verdict was thirty years. The appeal is due to be heard in Venice in the autumn. I do not think we can expect any new developments. Recently on the phone you said that you were more or less familiar with the story up to the autumn of 1980. The series of ghastly crimes continued after that time. That same autumn in Vicenza, a prostitute by the name of Maria Alice Beretta was killed with a hammer and an axe. Six months later, Luca Martinotti, a grammar school pupil from Verona, succumbed to injuries sustained when an Austrian casemate on the banks of the Etsch, used as a shelter by drug addicts, was torched. In July 1982, two monks, Mario Lovato and Giovanni Pigato, both of advanced years, on their customary walk of an evening round the quiet streets near their monastery, had their skulls smashed in with a heavy-duty hammer. After that killing, a Milan news agency received a letter from the Organizzazione Ludwig, which had already claimed responsibility for the crimes in the autumn of 1980, as you know. If I remember correctly, in the second letter the group claimed that their purpose in life was to destroy those who had betrayed God. In February, the body of a priest, Armando Bison, was found in the Trentino. He lay bludgeoned in his own blood, and a crucifix had been driven into the back of his neck. A further letter proclaimed that the power of Ludwig knew no bounds. In mid-May of the same year, a cinema in Milan, which showed pornographic films, went up in flames. Six men died. Their last picture show bore the title

Lyla, profumo di femmina.

The group claimed responsibility for what they described as a blazing pyre of pricks. In early 1984, on the day after Epiphany, a further arson attack, which also remained unsolved, was made on a discotheque near Munich's main station. It was not until two weeks later that Furlan and

Abel were apprehended. Wearing clowns' costumes, they were carrying open petrol canisters in perforated sports bags through the Melamare disco at Castiglione delle Stiviere, not far from the southern shore of Lake Garda, where that evening four hundred young people had come together for the carnival. It was only by a hair's breadth that the two escaped being lynched by the crowd on the spot. So much for the principal points of the story. Apart from providing irrefutable evidence, the investigation produced nothing that might have made it possible to comprehend a series of crimes extending over almost seven years. Nor did the psychiatric reports afford any real insight into the inner world of the two young men. Both were from highly respected families. Furlan's father is a well-known specialist in burn injuries, and consultant in the plastic surgery department at the hospital here. Abel's father is a retired lawyer, from Germany, who was head of the Verona branch of a Dusseldorf insurance company for years. Both sons went to the Girolamo Fracastro grammar school. Both were highly intelligent. After the school-leaving examinations, Abel went on to study maths and Furlan chemistry. Beyond that, there is little to be said. I think they were like brothers to each other and had no idea how to free themselves from their innocence. I once saw Abel, who was an outstanding guitar player, on a television programme. I think it was in the mid-1970s. He would have been fifteen or sixteen then. And I remember that his whole appearance and his wonderful playing affected me deeply.

Salvatore had come to the end of his account, and night had fallen. Crowds of festival-goers released from their tour buses were gathered outside the arena. The opera, said Salvatore, is not what it used to be. The audience no longer understand that they are part of the occasion. In the old days the carriages used to drive down the long wide road to the Porta Nuova in the evenings, out through the gateway, and westward under the trees along the glacis, skirting the city, till nightfall. .Then everyone turned back. Some drove to the churches for the "Ave Maria della Sera", some stopped here on the Bra and the gentlemen stepped up to the carriages to converse with the ladies, often till well into the dark. The days of stepping up to a carriage are over, and the days of the opera also. The festival is a travesty. That is why I cannot bring myself to go into the arena on an evening liKe this, despite the fact that opera, as you are aware, means a great deal to me. For more than thirty years, said Salvatore I have been working in this city, and not once have I seen a production in the arena. I sit out here on the Bra, where you cannot hear the music. Neither the orchestra nor the choir nor the soloists. Not a sound. I listen, as it were, to a soundless opera.

La spettacolosa Aida

, a fantastic night on the Nile, as a silent film from the days before the Great War. Did you know, Salvatore continued, that the sets and costumes for the

Aida

being performed in the arena today are exact replicas of those designed by Ettore Fagiuoli and Auguste Mariette for the inauguration of the festival in 1913? One might suppose no time had passed at all, though in fact history is now nearing its close. At times it really does seem to me as if the whole of society were still in the Cairo opera house to celebrate the inexorable advance of Progress. Christmas Eve, 1871. For the first time the strains of the

Aida

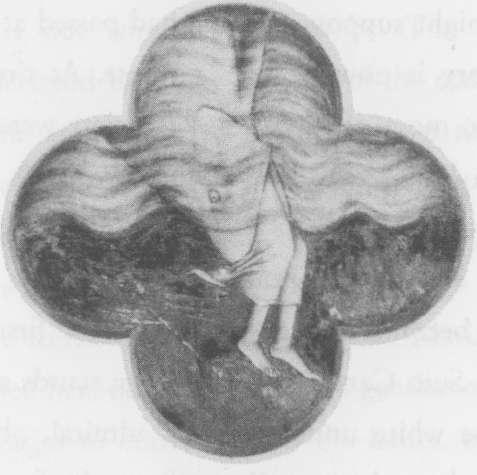

overture are heard. With every bar, the incline of the stalls becomes a fraction steeper. The first ship glides through the Suez Canal. On the bridge stands a motionless figure in the white uniform of an admiral, observing the desert through a telescope. You will see the forests again, is Amanoroso's promise. Did you also know that in Scipio's day it was still possible to travel from Egypt to Morocco under the shade of trees? The shade of trees! And now, fire breaks out in the opera house. A crackling conflagration. With a crash the seats in the stalls, together with all their occupants, vanish into the orchestra pit. Through the swathes of smoke beneath the ceiling an unfamiliar figure comes

floating down.

Di morte l'angelo a noi s'appressa. Già veggo il ciel discindersi.

But I digress. With these words, Salvatore stood up. You know how I am, he said as he took his leave, when it is getting late. I for my part, however, remained on the piazza for a long time with that image of the descending angel before my eyes. It must have been after midnight, and

the waiter in the green apron had just made his last rounds, when I imagined I heard a horse's hooves on the cobbled square and the sound of carriage wheels; but the carriage itself did not materialise. Instead, there came to my mind pictures of an open-air performance of

Aida

that I had seen in Augsburg as a boy, accompanied by my mother, and of which hitherto I had not had the slightest recollection. The triumphal procession, consisting of a paltry contingent of horsemen and a few sorrow-worn camels and elephants on loan from Circus Krone, as I have recently discovered, passed before me several times, quite as if it had never been forgotten, and, much as it had then in my boyhood, lulled me into a deep sleep from which - though to this day I cannot really explain how - I did not awake till the morning after, in my room at the Golden Dove.

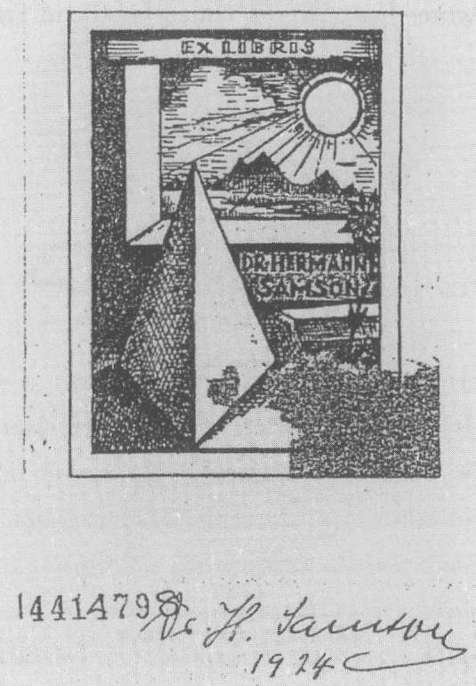

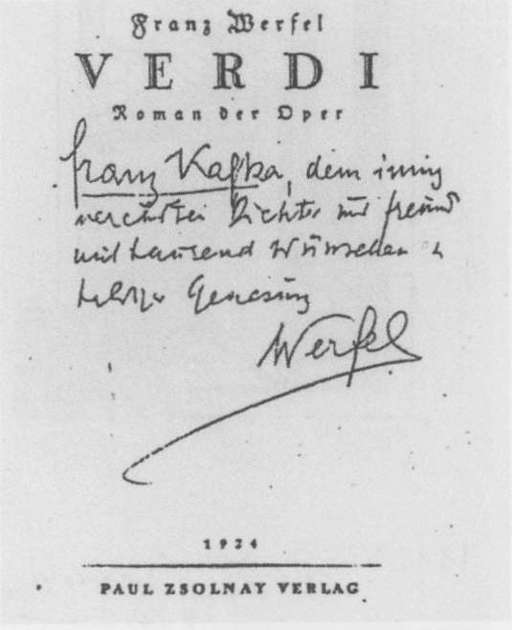

By way of a postscript, I should perhaps add that in April 1924 the writer Franz Werfel visited his friend Franz Kafka

in Hajek's laryngological clinic in Vienna, bearing a bunch of roses and a copy of his newly published and universally acclaimed novel, with a personal dedication. The patient, who at this point weighed a mere 45 kilograms and was shortly to make his final journey to a private nursing home at Klosterneuburg, was probably no longer able to read the book, which may not have been the greatest loss he had to bear. That at least was my own feeling when I leafed