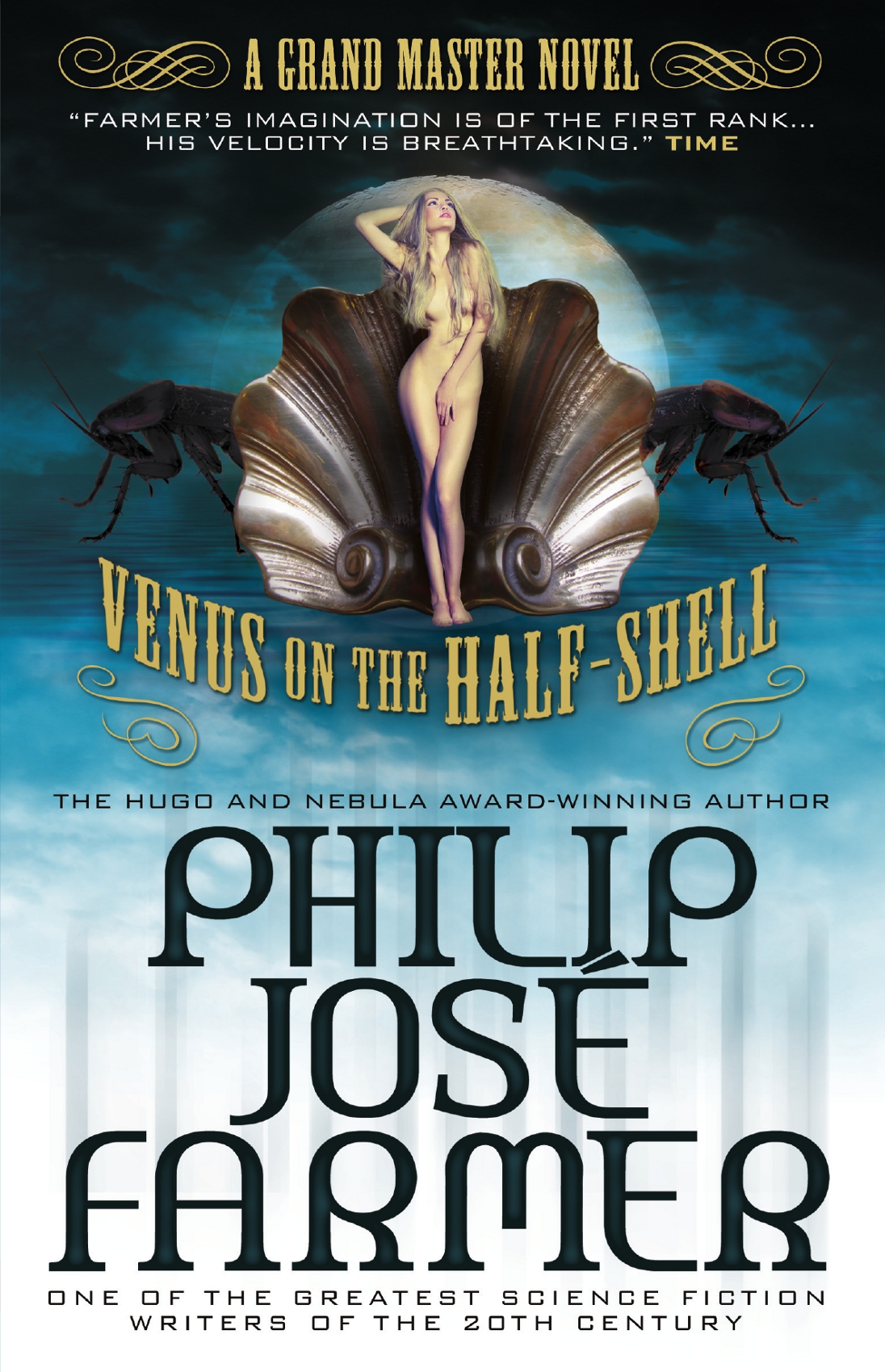

Venus on the Half-Shell

Read Venus on the Half-Shell Online

Authors: Philip Jose Farmer

ALSO FROM TITAN BOOKS

CLASSIC NOVELS FROM

WOLD NEWTON SERIES

The Other Log of Phileas Fogg

PREHISTORY

Time’s Last Gift

Hadon of Ancient Opar

SECRETS OF THE NINE: PARALLEL UNIVERSE

A Feast Unknown

Lord of the Trees

The Mad Goblin

Tales of the Wold Newton Universe

GRAND MASTER SERIES

Lord Tyger

The Wind Whales of Ishmael

Flesh

JOSÉ

FARMER

VENUS

VENUS ON THE HALF-SHELL

ON THE HALF-SHELLTITAN BOOKS

VENUS ON THE HALF-SHELL

Print edition ISBN: 9781781163061

E-book edition ISBN: 9781781163078

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: December 2013

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Copyright © 1974, 2013 by the Philip J. Farmer Family Trust. All rights reserved.

“Why and How I Became Kilgore Trout” copyright © 1988, 2013 by the Philip J. Farmer Family Trust. All rights reserved.

“The Obscure Life and Hard Times of Kilgore Trout” copyright © 1973, 2013 by the Philip J. Farmer Family Trust. All rights reserved.

“Jonathan Swift Somers III: Cosmic Traveller in a Wheelchair” copyright © 1977, 2013 by the Philip J. Farmer Family Trust. All rights reserved.

“Trout Masque Rectifier” copyright © 2012 by Jonathan Swift Somers III. All rights reserved.

“More Real Than Life Itself: Philip José Farmer’s Fictional-Author Period” copyright © 2008, 2013 by Christopher Paul Carey. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

VENUS

VENUS ON THE HALF-SHELL

ON THE HALF-SHELLForeword

Why and How I Became Kilgore Trout

By Philip José Farmer

Preface

The Obscure Life and Hard Times of Kilgore Trout

A Skirmish in Biography

By Philip José Farmer

1

The Legend of the Space Wanderer

6

Shaltoon, the Equal-Time Planet

Dedicated to the beasts and the stars.

They don’t worry about free will and immortality.

WHY AND HOW I BECAME KILGORE TROUT

BY PHILIP JOSÉ FARMER

Not until I reread

Venus on the Half-Shell

in preparation for this foreword, and read the reviews and letters resulting from it, did I remember how much fun I had had with it.

When I sat down to the typewriter to begin it, I was Kilgore Trout, not Philip José Farmer. The ideas, characters, plot, and situations rushed in, crowding at my brain’s front door. When they surged in, they swirled around, hand-in-hand, like super barn dancers or well-orchestrated members of the lobster quadrille. What a blast it was!

Six weeks later, the novel was done, but, all that while, the music was from Kant, Schopenhauer, and Voltaire. The caller was Epistemology, who looked a lot like Lewis Carroll. My wife knew I was having a good time because she could hear my laughter coming up the basement stairs to the kitchen.

I had been having a moderate writer’s block with the thencurrently scheduled novel. I was making slow and often halting progress. But, once I put that novel aside for the time being and adopted the persona of Kilgore Trout, sad-sack science fiction author, I wrote as if possessed by a degenerate angel. Which is what poor old Trout was, in fact.

The beginning of this project was in the early 1970s when I vastly admired and was wildly enthusiastic about the works of Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. I was especially intrigued by Kilgore Trout, who had appeared in Vonnegut’s

God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater

and

Slaughterhouse-Five.

Trout was to appear in

Breakfast of Champions

, but that had not been published then.

While rereading

Rosewater

(in 1972, I believe) for the fifth time, I came across the part where Fred Rosewater picks up one of Trout’s books in the pornography section of a bookstore. It’s a paperback (none of Trout’s works ever made hardcovers) titled

Venus on the Half-Shell.

On the back cover is a photograph of the author, an old bearded man looking “like a frightened, aging Jesus”, and below it is an abridged version of “a red-hot scene” in the book.

The section regarding

Venus

differs from others, which describe the plots of Trout’s stories. Thus, Vonnegut, via Trout, makes his satirical or ironic points about our Terrestrial society and the nature of the Universe.

Venus

has no descriptions of the plot, and the hero is known only as the Space Wanderer. Aside from the abridged text on the back cover, there is no inkling of what the book is about.

At that moment, rereading this part, a pitchfork rose from my subconscious and goosed my neural ganglia. In short, I was inspired. Lights went on; bells clanged.

“Hey!” I thought. “Vonnegut’s readers think that Trout is only a fictional character! What if one of his books actually appeared on the stands? Wouldn’t that blow the minds of Vonnegut’s readers?”

Not to mention mine.

And, I thought, who more fitted to write

Venus

than I, a sad-sack science fiction writer whose early career paralleled Trout’s? I’d been ripped off by publishers, had to work at menial jobs to support myself and family while writing, had suffered from the misunderstanding of my works, and had had to endure the scorn of those who considered science fiction to be a trashy genre without any literary merit. The main difference between Trout and me was that I had made a little money then, and none of my stories had been confined to sleazy pornographic magazines where they appeared, as in Trout’s case, as fillers to accompany the photographs of naked or half-clad women. Although it was true then that the general public and the epicenous academics thought of science fiction as only a cut above pornography.

My heart fired up like a nova, I wrote to David Harris, science fiction editor of Dell (Vonnegut’s publisher), proposing to write

Venus

as if by Kilgore Trout. He replied that he thought the idea was great, and he gave me Vonnegut’s address so that I could write him to ask for permission to carry out the project. I did not hesitate. After all,

Venus

would be my tribute to the esteemed Vonnegut. I sent him a letter outlining my proposal. Many months passed. No reply. I sent another letter, but many more months passed before I decided that I’d have to phone Vonnegut. David Harris gave me Vonnegut’s number.

I had to nerve myself up to phone Vonnegut. He was a very big author, and I was a member of a group, science fiction writers, for whom he had expressed a certain amount of disdain. But, when I did call him, he was very pleasant and not at all patronizing. He said that he did remember my letters, though he did not explain why he had not replied. I re-outlined my ideas, and, in arguing against his resistance to them, said that I strongly identified with Trout. He replied that he, too, identified with him. And he was afraid that people would think that the book was a hoax.