Vegetable Gardening (40 page)

To avoid this problem, rotate crops, grow resistant varieties, and cover the plants with a

floating row cover

(a cheesecloth-like material that lets air, water, and sun in, but keeps bugs out; see Chapter 21).

Colorado potato beetle:

Colorado potato beetle:

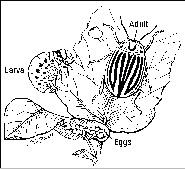

The most destructive potato pests, these 1/2-inch-long, tan- and brown-striped adult beetles lay yellow eggs in clusters on the undersides of potato leaves, starting in early summer. After the eggs hatch, the dark-red larvae feed on the leaves and can quickly destroy your crop (see Figure 6-4).

Figure 6-4:

Colorado potato beetle eggs, larvae, and adults love potato leaves.

Control these insects by growing resistant varieties, crushing their eggs on sight, handpicking the young beetles, mulching with a thick layer of hay to slow their spread, and spraying the biological spray Bt ‘San Diego', which is specifically designed to kill young potato beetles but doesn't harm other insects, animals, or people, on the larvae. Potatoes can withstand significant potato beetle leaf damage and still produce. You just won't receive as large of a crop.

Onion maggot:

Onion maggot:

This pest's larvae attack the bulbs of developing onions, causing holes, opening the bulb to infection from disease, and making them inedible. Onion maggots like cool, wet weather. To control onion maggots, place a floating row cover over young seedlings after the weather warms to around 70 degrees. Doing so prevents the adult flies from laying eggs on the young plants.

Potato scab:

Potato scab:

This fungal disease causes a potato's skin to turn brown with a corky texture. Tubers with potato scab are unattractive but still edible. Control this cosmetic disease by planting resistant varieties and rotating your crops.

Wireworm:

Wireworm:

These jointed, hard-shelled, tan-colored, 1-inch worms feed on underground tuber roots as well as the bulbs of a number of crops. They're generally a problem with recently sodded soil. Control this pest by setting potato traps before your root crops begin maturing. Spear a potato piece on a stick and bury it 2- to 4-inches in the ground; the wireworms should infest the potato piece. Dig up the piece after 1 week and then destroy it.

Chapter 7: Sweet and Simple: Beans and Peas

In This Chapter

Growing bean and pea varieties of different heights, colors, and flavors

Growing bean and pea varieties of different heights, colors, and flavors

Planting beans and peas in your garden

Planting beans and peas in your garden

Caring for your beans and peas

Caring for your beans and peas

Harvesting your crop

Harvesting your crop

One vegetable that you can always rely on is the bean. So for ensured success in your first garden, plant some bean seeds. When I teach gardening to beginner groups, the first plants that I talk about are bean plants — and for good reason. Bean seeds are large and easy to plant, they grow easily, and they don't require lots of extra fertilizer or care. Within 60 days, you're bound to have some beans to eat. With beans, satisfaction is as guaranteed as it gets in the vegetable gardening world. In fact, they're even more forgiving than tomatoes!

Peas are in the same legume family as beans; other crops in this family include clover and alfalfa, but you don't eat them (unless you grow sprouts!). Like beans, peas also have large seeds and require little care. The only difference between the two is that peas like cool weather to grow and mature, whereas beans like it warm. If you get the timing right for beans and peas, you'll have lots of legumes rolling through your kitchen door; just use the guidelines in this chapter to get started. (See the appendix for a general planting guide for selected beans and peas.)

A Bevy of Beans: Filling Your Rows with Bean Family Plants

All bush, pole, and dried beans are members of the

Fabaceae

family. In this section, I classify beans according to their growth habits and usage (that is, whether you eat them fresh or dried). Here are the categories:

Bush beans:

Bush beans:

These beans get their name because they grow on a bush. They tend to produce the earliest crops, maturing all at once (within a week or so of each other); you have either feast or famine with these types.

Pole beans:

Pole beans:

These beans need staking and usually grow on poles. They tend to mature their crops later than bush beans, but pole beans continue to produce all season until frost or disease stops them. (Luckily, home gardeners generally don't have to worry about disease resistance with their bean plants.)

Dried beans:

Dried beans:

These are actually varieties of bush or pole beans. You can eat them fresh, like bush or pole beans, but they're better if you allow them to dry and then just eat the bean seeds. Growing dried beans is easy: Just plant them, care for them, and harvest them when the pods are dried and the plants are almost dead.

Bush and pole beans actually are the same type of bean, just with different growth habits. Bush and pole beans often are called

snap beans

because they snap when you break their pods in half. Another name for these beans is

string beans,

because early varieties had a stringy texture. (Modern varieties don't have this texture, so this name isn't commonly used today.) Yellow snap varieties mature to a yellow color and are called

wax beans.

Don't get lost in the snap versus string discussion. Those are just names people have given to a bean eaten before the seeds inside begin to form.

Beans harvested at different stages can be called different names. Consider the following:

Beans harvested at different stages can be called different names. Consider the following:

A bean harvested when it's young, before seeds have formed, is called a

A bean harvested when it's young, before seeds have formed, is called a

snap bean.

They come in green, yellow, or purple depending on the variety.

If a bean matures further and you harvest it when it's still young but the bean seeds are fully formed, it's called a

If a bean matures further and you harvest it when it's still young but the bean seeds are fully formed, it's called a

shell bean.

If the pod dries on the plant and then you harvest it, it's called a

If the pod dries on the plant and then you harvest it, it's called a

dried bean.