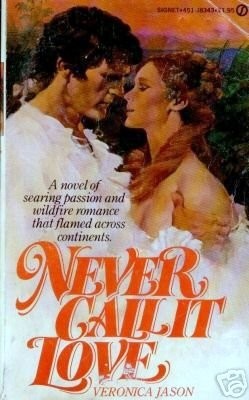

Never Call It Love

Read Never Call It Love Online

Authors: Veronica Jason

NEVER CALL IT

LOVE

Veronica Jason

A SIGNET BOOK

NEW AMERICAN

LIBRARY

Times Mirror

A

BLAZING LOVE THAT WAS BORN IN SMOLDERING HATE

When

beautiful young Elizabeth Montlow lost her innocence, it was not on a night of

romantic dreams. It was in an act of savage violence by a man seeking

vengeance.

Yet

from this brutal beginning came an all-consuming passion that would take

Elizabeth from the sheltered eighteenth-century English countryside to a lonely

manor in Ireland, where she was forced to share her man with his ravishing and

ruthless mistress... to a nightmare exile on a lush and licentious Caribbean

island, where lust and murder went hand in hand... to the depths of the lawless

American wilderness, where two men played a monstrous game of heart-wrenching

deception with her as the stake....

Here

is a burning saga of a woman swept up in a whirlwind of desire that carried her

to the ends of the earth in search of her destiny....

CONQUEST

Elizabeth

lay naked before this man, as the cord he had tied around her wrists bit into

her straining flesh.

She

felt his gaze moving over her body. Then with startling gentleness his hand

closed over her breast.

For

perhaps a minute she stayed rigid, resisting the odd little thrills that seemed

to travel from her breast to somewhere deep within. Then all the stiffness went

out of her. Something was happening, something she had never experienced

before, a sense of warm, liquid swelling. His hand left her breast, moved

skillfully downward. Dimly she was aware that her hips were moving, as if her

body had a will of its own...

Later,

as she lay there, spent, she tried to protest, "It was only my body."

But

even as Elizabeth spoke, she knew that no part of her now was safe from this

masterful man's fiery passion....

NEVER CALL IT LOVE

New

American Library, Inc., 1633 Broadway, New York, New York 10019.

Copyright

©

1978 by Veronica Jason All rights reserved

Signet,

Signet Classics, Mentor, Plume, Meridian and NAL Books

are published by The

New American Library, Inc., 1633 Broadway, New York, New York 10019

First

Signet Printing, December, 1978

PRINTED

IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

There

were five of them cloaked and eye-masked, crouching below sidewalk level in the

pitch-black area-way. Moments earlier, when one of them had seen the

approaching figure, they had exchanged a few excited whispers. Now they waited

in tense silence. They knew nothing about the woman moving along the sidewalk

except that her footsteps were light and young, and that she was alone. But

that was enough to know. It made her exactly the sort of prey they had hoped to

find that night.

To

seventeen-year-old Anne Reardon, the London street seemed utterly deserted. She

saw no movement, and heard no sound except that of a fitful November wind,

rattling the leafless ivy vines that clung to the tall house fronts and making

the widely spaced oil streetlamps gutter despite their protective glass

lanterns.

She

quickened her steps. With a mittened hand she drew closer around her the hooded

cloak that hid her reddish-blond hair and framed her small face. It was a

somewhat plain face, thin and slightly freckled, but appealing in its youth and

gentleness. There was no reason for her to be afraid, she told herself, even

though long stretches of blackness lay between the dim patches of moving light

cast by the streetlamps. This was a fine neighborhood. Only the rich and

respectable lived in these tall stone houses, with their fanlighted doors that

here and there spilled warm light onto front steps and areaway railings. Too,

in only a few minutes she would reach her

guardian's lodgings in Darnley Square.

Nevertheless, she found herself wishing that she had stayed back there with

Auntie Maude in the disabled carriage.

The

accident had occurred without warning. A barrel-laden cart, drawn by a scrawny

horse, had rounded the corner from a side street and locked its left wheel with

the right-hand rear wheel of their hired carriage. Sitting beside her plump

chaperon, Anne had listened to the carriage driver and the carter exchange

invectives so violent that she expected the men at any moment to come to blows.

Finally, though, they had settled down to trying to disentangle their vehicles.

It

had proved to be a difficult task. Minutes passed, while the grunting, swearing

men struggled with the locked wheels. Anne had felt a growing anxiety. It was

now not more than a quarter of an hour to seven o'clock, the hour appointed for

the signing of the marriage contract. They would all be waiting: Thomas Cobbin,

the shy twenty-year-old she scarcely knew, but who nevertheless, in a few

months' time, would be her husband; his middle-class, highly respectable

parents; and Anne's Anglo-Irish guardian, Sir Patrick Stanford, fourth baronet.

It

would not do to arrive late on such an important occasion, especially since her

prospective parents-in-law, a London ironmonger and his wife, had not seemed

over-eager to have their son marry an Irish girl, even a baronet's ward. Only

the generous dowry offered by Sir Patrick had brought them to the point of

signing the contract.

The

carriage tilted slightly. From the suddenly relieved voices of the two straining

men, she had known that the locked wheels were almost free of each other. Then

the carriage horse, frightened by a scrap of paper blowing along the street,

had backed up in the shafts. With a sound of rending wood, the wheels locked

again.

Desperately

Anne had turned to her relative. "You stay

here, Auntie," she had

said, through the fluent curses of the two men in the street. "I'm going

to walk the rest of the way. It's not far."

Auntie

Maude's round face was appalled. "At night? Through this wicked town?"

Never

before out of Ireland, Maude Reardon feared and hated London. The noisy traffic

along the Strand. The dirty, ragged urchins who, if you stepped into St.

James's Park to rest your eyes on a bit of green, would surround you, beg for

coppers, and then reward your generosity by twisting a button from your best

mantle or filching your handkerchief from your pocket. She hated the smart

Oxford Street shops where the clerks sneered at her Irish accent. And she had

been terrified one evening when a hired carriage, unable to get through a

street where two houses were on fire, had taken her on a detour through Covent

Garden. With horror she had stared at the painted bawds of all ages sauntering

along the sidewalks, or calling, bare-breasted, from upper windows. She had

seen gin-soaked men and women reeling across the cobblestones, and heard young

boys hawking tickets for elevated seats from which to view the next day's

double attraction at Newgate—the hanging of a fifteen-year-old girl pickpocket,

and the drawing and quartering of a famous highwayman.

Ireland

was poor, true enough, and not unacquainted with violence. But no part of that

isle, Maude Reardon felt sure, held anything to match the filth and danger and

debauchery of London under the reign of His Gracious Majesty George III.

Anne

had said, "I must, Auntie. I can't be late. And this is a respectable

street. As soon as the carriage is freed, you can join us."

"I

forbid you!" Maude Reardon's pleasant face did its best to look stern.

"You know I cannot keep up with you,

not with my asthma. And you can't go

through the streets alone at night. What would Sir Patrick say?"

"Please,

Auntie! It's because of him I must hurry. I cannot bear to have him worried

or... or annoyed with me." She had slipped out of the carriage, and

ignoring the anxious cry her aunt sent after her, hurried away down the street.

It

was true that what distressed her most was the thought of displeasing, not the

Cobbins, but Patrick. Always she had shrunk from the idea of doing anything to

bring disapproval to his face, that rough-hewn face that some might consider

cold and proud, but which for her had never held anything but kindness. And he

had gone to such effort to secure her future. A month ago he had brought her

and Auntie Maude over from Ireland and settled them in lodgings near Grosvenor

Square. Twice he had summoned them to his own Darnley Square lodgings to meet

the Cobbins and their son, once for morning coffee, and once for supper. Behind

the scenes, he had worked out the marriage settlement with the elder Cobbin.

As

always at the thought of her guardian, Anne felt a twist of hopeless longing.

Only in her wildest daydreams had she pictured herself as Patrick Stanford's

bride. At thirty-two he was almost twice her age. And obviously his emotion for

her, compassionate and paternal, had not changed since she, an orphaned

ten-year-old, had been brought to Stanford Hall as his ward. Besides, when he

chose to marry, he would select a fine lady, either from the Anglo-Irish

aristocracy or from among the English beauties he mingled with for a few weeks

each year during the London season.

But

at least she had sometimes hoped that she would be allowed to live out her life

at Stanford Hall, where she could see him almost every day. See him dismount

from the rangy bay hunter in the cobblestoned courtyard after

a run through

the misty countryside. See him in his study, dark face frowning over the

account books his half-brother, Colin, had spread before him. See him at the

long, candlelit table in the drafty old dining hall, sometimes abstracted and

silent, sometimes good-natured and teasing. Yes, it would have been wonderful

if she could have stayed there always, silently loving him, and someday helping

care for the children another woman would give him.

But

it was foolish and ungrateful of her to want that. As Patrick plainly realized,

it was better for her to marry some quiet, decent man and have children of her

own.

It

was apparent now that the distance between the disabled carriage and Darnley

Square was greater than she had thought. Nor had she expected the street to be

this deserted. Perhaps five minutes ago an old-fashioned sedan chair, its

white-wigged occupant dimly visible through the glass, had moved past her along

the street, with a torch-carrying linkboy running ahead of the bearers. But the

sedan chair had soon disappeared around a curve. Since then there had been no

street traffic and no other pedestrians. Only darkness, broken at long

intervals by wavering yellow pools of light cast by the streetlamps. Only the

cold wind tearing at her cloak and rattling the ivy branches. Only this vague

feeling that had crept over her within the last minute or two, this

presentiment that some terrible danger lurked nearby.

A

wild, inhuman scream from somewhere at her right. Heart lurching, she stopped

short. A lean cat, white or light gray, shot between two pickets of an areaway

railing and scurried across the street. Anne clutched the railing until her

heartbeats began to slow. Then, smiling a little in her relief, she hurried

onward. It could not be much farther now. A few yards ahead, the street curved.

And beyond that curve, surely, she would see Darnley Square. She passed another

areaway.

Behind

her, there below street level, one of the masked figures gestured silently. He

led them softly up the stone steps. Then, sure that surprise and terror would

render her voiceless for the necessary few seconds, they all rushed after her.

At

the sound of running feet, she whirled around. Two of them seized her arms. As

she opened her mouth to scream, one of them who had moved behind her slipped a

cloth gag between her jaws. Too paralyzed with terror to struggle, she felt

herself lifted in someone's arms.

A

voice said, "Christopher! You've lost your hat." It was a male voice,

and young.

The

man who held her said in a low, angry tone, "Then pick it up, you damn

fool. And don't use my name like that."

He

had carried her down the areaway steps now. "Open the door," he said

impatiently, "and strike some lights."

She

had begun to struggle. The arms holding her tightened their grip, pinioning her

own arms to her sides. She heard a door creak open, and then, after she was

carried into deeper blackness, close behind her.