Under the Hawthorn Tree (7 page)

Read Under the Hawthorn Tree Online

Authors: Marita Conlon-Mckenna

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #General

That night they slept in Kineen, as it was rumoured that the soup kitchen would re-open at midday again the next day. During the night an old man shook them and told them to be on their way, as the heathens would try to convert them in the morning and if they took another mug of soup they may as well take the Queen’s shilling. The children

were puzzled, but simply ignored him.

The following morning they positioned themselves mid-way in the starving group. Gradually they became aware of a kindly-looking gentleman and two women moving among the ragged crowd. At times the younger woman would emerge from the crowd with a young boy or girl in tow, or a toddler in her arms, and make her way to a large house at the end of the village. She would knock at a green door, then disappear inside and re-emerge on her own a few minutes later.

Eily wondered what they were doing. Were they taking the children to some kind of orphanage or workhouse? They were getting nearer and nearer. The older woman had begun to chat to Peggy. She was asking her was she on her own. Peggy turned and pointed out Eily and Michael, then came the next question: ‘But where are your parents?’

Eily reached out and pulled at Peggy who was staring blankly at the lady, wondering what she was meant to say. Frantically Eily’s eyes scanned the crowd. In the far distance she spotted a red-haired woman sitting on a doorstep, her husband standing beside her.

‘There they are, Miss,’ replied Eily, quickly pointing out the pair. The old lady looked doubtful. Quickly Eily waved at the red-haired woman. Their

eyes met and the woman nodded back at Eily, wondering in her own mind who that lassie with the long fair hair was. The old lady, satisfied, moved on.

Once they had received their portion of the thick mutton stew, they made their way back to the edge of Kineen. The three children felt they wanted to get back on their way, but Joseph pleaded with them to stay, reluctant to lose his new-found friends. They explained to him about the aunts and how they hoped Mother and Father would turn up there. He wanted to stay in Kineen for another few days and then make his way to one of the harbour ports and try to get passage on one of the ships sailing for Liverpool.

It was with heavy hearts that they took leave of one another. Michael had to swallow a lump in his throat as he said yet another goodbye.

CHAPTER 8

Beside the Lake

THE CHILDREN KEPT WALKING ON

. Peggy had two huge blisters on her foot. Every few hours Eily smeared the foot with Mary Kate’s ointment. For the most part, the skin on the soles of their feet was like blackened leather. Eily’s hands were hard and calloused, the skin scarred with the constant weight of all she had to carry. She had developed a touch of ‘the flux’, and suspected the slightly rancid mutton stew from Kineen. She chewed the herbal remedy of Mary Kate’s, hoping it would ease her nausea and the cramps in her stomach.

They had stopped for a rest when they became aware of a smell – more like a stench. Even worse than the time the potatoes had rotted.

‘Eily, what could it be?’ questioned Michael. ‘Do you think everything around us is going to rot and die?’

Peggy and Eily made for a clump of bushes to relieve themselves. Suddenly the stench, with an even fouler undertone, washed over them. Eily saw it and turned, hoping that Peggy hadn’t noticed, but Peggy’s face was white with fear.

It was a man – well, what was left of him. The skin was rotted and all different colours. He was thin, so thin that his bones already showed. Eily could feel pinpricks of sweat across her brow and her stomach turning. Peggy had screwed up her eyes and was pulling at her dress. Almost in unison they got sick in the bushes. Once their stomachs were empty and the heaving had stopped, they galloped back to Michael. One look at their faces and he knew something terrible had happened.

‘What is it, girls? What is it?’ he kept on.

In between tears and sobbing, they managed to tell him.

‘That poor soul,’ cried Eily. ‘To die all alone in the middle of nowhere, starved and with no family or friends.’

‘We must say a prayer for him,’ said Michael in a low voice. He broke two twigs and fashioned them into a cross, tying them with some long pieces of grass.

They all walked back towards the bushes.

‘I don’t want to get sick again,’ wailed Peggy,

keeping a few steps back behind the others. They stopped short a few yards away from the body. Michael pushed the simple cross into the ground.

‘What will we say?’ asked Michael.

‘An “Our Father”,’ replied Eily. When it was said, Eily asked God to remember this poor lost man.

As quickly as they could they gathered up their stuff, wanting to get away from that dreadful place, so much so that they did not stop walking until they noticed a towering green forest that stretched for miles. It reminded them of the forest at home near Duneen, and they suddenly realised that it was almost two weeks since they had left home. Seeking comfort, the children slipped off the road and into an almost familiar world. The huge trees reached right up to touch the sky, sounds were muffled and they seemed to be walking on a dull carpet of pine needles and moss. Very little sunlight filtered through, but there in the calm and peace, with only the odd coo of a wood-pigeon, the world seemed a better place.

They kept a good eye on the road in the distance, moving parallel to it. Secure in the forest, they relaxed. The odd small startled animal ran across their path and in the far distance the muffled sound of a fast-running mountain stream could be heard.

Time had stopped still in this place. They remembered past times playing hide-and-seek in the woods near home – now they did not have the energy even to run.

After about two hours’ walking they all sat down. Peggy and Michael were exhausted. Peggy began to cry, her breath coming in racking sobs. She could not stop. Eily pulled her on to her lap. She could feel how light Peggy was – no sign of the plump young arms and legs. Her skin seemed barely to cover her bones and her ribcage stuck out. Eily laid her head against her little sister’s head, and the tears slid soundlessly down her face. A total sense of hopelessness washed over her. Oh how she longed for Mother to come and take care of them all, or Father to tell them what to do.

Michael looked at them. He could feel Eily’s sorrow and grief.

‘We’re going to die like the rest of them, aren’t we?’ he whispered. He was scared. He had always had so many plans for when he was older. He knelt down beside Eily and they hugged each other. They cried, each voicing their own fears.

‘I wanted to play on a hurling team like the big fellows, and some day learn to ride a horse and maybe even have a place of my own,’ said Michael.

‘I wanted to have a fine wool dress with a lace

collar and combs in my hair. Maybe then when I was older I would fall in love and get married like Mother and have babies of my own,’ sobbed Eily.

They looked at Peggy. She had calmed down a bit. ‘Just a doll of my own and maybe to go to school and best of all to be like Eily,’ she said in a shaky little voice.

Eily held her close, overwhelmed with the love she felt for her brother and sister. She felt her heart would burst with the sadness of it all.

Suddenly Peggy laughed. ‘Look at Michael. His face is all blotchy and his eyes are so red.’

Then Michael looked at the girls. Their hair was wild, and they both had runny noses and raw-looking eyes. He half-hiccupped and laughed. Eily couldn’t help smiling at the silliness of it all, and within a few seconds they were laughing out loud and blowing their noses.

‘What eejits we are,’ joked Eily. ‘We’re still alive. We’re tired and hungry and on our own, but we have each other and we can still walk and forage. We’ll get to Nano and Lena’s even if it takes us a month.’

The bout of crying had released a lot of the tensions and they all felt in some way refreshed and renewed in their purpose.

The forest trail began to climb slightly and they

planned to follow it until dusk and spend the night there, knowing that the next morning they would have to get back down to the road.

When they did, the road seemed less crowded. Two funerals passed them, and two middle-aged women fell into step with Eily. One carried a wasted-looking baby wrapped inside her shawl. They felt it was their duty to inform Eily of all the latest gossip roundabouts.

‘Lovey, did you hear tell of the little village of Dunbarra? The poor old priest went calling on four of the cottages and found all in them dead of the famine fever and huge rats swarming the place. They had to open a burial pit a mile outside the village to throw all the bodies of those that died into it.’ The women continued, with each story worse than the one before. Eily felt faint and had to sit down on a hillock of grass. Michael and Peggy came over to see what was wrong. The women, terrified of the fever, quickened their pace and were soon gone. Eily refused to tell the others what had upset her so.

They looked across the fields and in the distance they could see a group of people working. Two men further up the road had crossed the stone wall and

were making for that field too. The children decided to follow. As they came nearer to the field, they could clearly see the ragged group kneeling on the ground lifting young turnips. They hurried over. An old man assured them that the farmer, an old bachelor, had died that very morning of the fever and that there was no harm in the poor trying to save themselves. The children split up and began to sink their hands into the damp mud and lift out the small pale turnips and place them in their pockets. Then Eily put them one after another in the food bag. Some poor creatures were eating them as soon as they lifted them, barely knocking the earth off. Eily tried to avert her eyes. Within about half an hour the field had been picked clean, as if it was harvest time. The group then disbanded and all went their separate ways.

At least the food bag was now fairly full, even if it was with food usually reserved for animals. The children kept going overland, climbing over the stone walls. The fields were carpeted with wild flowers and clover, the hum of honey bees droned in the still air. The sun blazed down, drying out the damp earth. They walked for about another two miles and suddenly became aware of the sparkle of the sun reflecting on water. It was a lake, and it stretched as far as the eye could see. High, thin

water reeds formed a circle around it and at times there were clear patches of sand and stony gravel over which the clear water lapped.

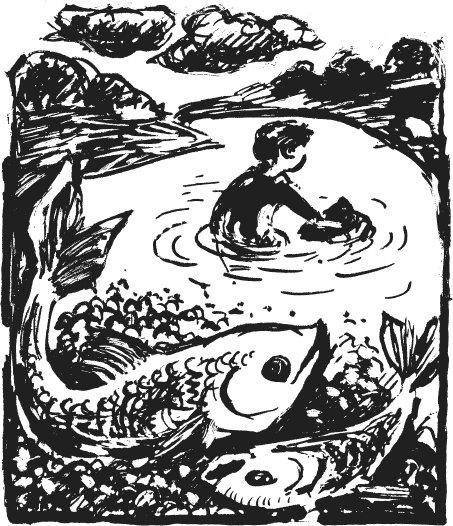

The children could hardly wait – they dropped all they were carrying and ran into the water. It was bliss. The coolness washed over them. They splashed each other and ducked their heads down under the water, filling their mouths with it and squirting it at each other. Then they got out and lay on the grass, stretching out to bake in the sun, and after about fifteen minutes they charged back into the water to cool down again. On the centre of the lake wild birds dived in and out and bobbed on the calm surface of the water.

Michael looked at the birds fishing. If only he had something to fish with, but he had no line or anything, not even a net. He watched the shallows of the lake and the odd time could make out a fish darting in and out among the water weeds near the rushes, or basking near the lily leaves. But how to catch one? That was the question.

He explained what he wanted to Eily. Suddenly she jumped up and emptied out the filthy sacking that was the food bag.

‘This will do, Michael. Go on, have a try!’

Michael looked very doubtful, but he searched around a bit and found a willow tree. Using the

blade, he cut a thin branch off it and pulled off the leaves. It was light but strong. He poked it through a small hole near the top of the bag. Then, wading into the water, he lowered the bag so that it filled with water and opened out. He kept it on its side.

Michael did not move. Two or three curious little fish swam past, and at last one went in to investigate. Quickly Michael lifted up the stick and bag, but he saw the fish dart away. He had to wait for the water to settle before beginning the whole procedure all over again. He stood still for about another hour before he was successful. Swiftly he lifted the bag out of the water. The fish struggled and tried to jump back in, but Michael flung the bag to the safety of the shore. The silver fish flipped and flapped and finally was still, giving up the struggle. Straight away Michael started to fish again and twenty minutes later two little sprats had joined the fish on the shore.

Now they had something to eat, but none of them was prepared to eat the fish raw.

‘We need a fire,’ said Peggy, sure that the others knew what to do. Michael and Eily looked at each other, but they didn’t know.

‘I remember Pat told me that his father could start a fire by rubbing flint stones together,’ suggested Michael.

‘Do you think you know what to do?’ asked Eily.

Michael scrabbled around till he found two likely-looking stones. The girls gathered up a heap of dry sticks and twigs, then Michael began to rub and then hit the stones off each other. After ten minutes his hands ached and he passed the stones to Eily. It was infuriating. They could see sparks coming off the stones, but just couldn’t get them to set the dry timber alight. Eily was just about to throw the stones on the ground with vexation, when she felt a spark burn her finger and realised that it had caught the sticks and was beginning to smoulder. Cautiously she blew and tried to encourage the flame to catch. Suddenly, as if in answer to a prayer, the fire began to burn.