Under the Hawthorn Tree (10 page)

Read Under the Hawthorn Tree Online

Authors: Marita Conlon-Mckenna

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #General

‘Hush, love. Hush, love,’ was all that Eily could manage.

All that day and night Eily sat with Peggy, stroking her hair and holding her hand, giving her the fever mixture and trying to cool her down. Michael went off in search of nettles and roots and herbs to mix with a bit of water to make a thin cold soup. At night Michael dozed off, but Eily forced

herself to stay awake. The little girl tossed and turned and sometimes cried out in pain. She had a nightmare about the dogs attacking her, and kept shouting ‘Dog, the dog,’ her eyes wide and staring, before collapsing back into a heavy sleep. Eily knew that Peggy didn’t know who she was with or where she was. Also she couldn’t help wondering, would they all get the fever now. Who would look after her if she got sick? She could feel her head bursting with the worry of it all. Eily kept checking Peggy’s skin. It was burning like fire with no sign of cooling down. However, there was no tinge of yellow to it at all. That was a good sign. Her skin glowed pink with her temperature and her two cheeks were a rosy red.

As she dozed lightly, Eily thought about Mother and Bridget, the baby nestled into her arms. Had Mother gone to join her little one in heaven? Eily opened her heart and prayed, ‘Don’t let Peggy die – don’t take away my little sister – keep her safe – let her get well.’

Eily dozed and when she woke up the early morning was damp. Her arms and back were stiff and sore. Peggy was still in a deep sleep, her breathing loud and far too fast.

Eily walked away a few yards to relieve herself and then took the can of water and gulped some

down; the rest she splashed on her face and back to try and wake herself up. She could send Michael for more when he roused himself. If only they had the fire. She picked up the flints, sparking them off each other in a temper. It caught some dried moss and began to smoulder! She hardly dared move as she angled a few twigs to catch the small flame. They were a bit damp and cold after the night and spluttered a little, but they took. Now at least they had the comfort of a bit of fire.

Michael and Eily both felt useless. There was very little they could do but sit and stay near Peggy. Michael roved around frantically to find something of substance to eat, but to no avail. Flower heads, grass, leaves, everything was being added to the water along with a tiny bit of grain, but it did nothing to kill the growing hunger pains in their stomachs. Michael kept his eyes constantly peeled for the sight of a rabbit or hare but never saw even the sign of one. It was hopeless. Soon both of them would be too weak to walk. They would have to do something.

Michael disappeared for the morning with a grim look on his face, and came back with some kind of creature skinned and cleaned out, but there was little eating in it. Cooked with the nettle leaves, it was disgusting, and a feeling of queasiness washed

over Eily as she forced herself to swallow it and later to try and keep it down.

That evening, with Peggy’s head resting in her lap, Eily couldn’t help but wonder what would have happened if they had gone to the workhouse with Tom Daly and the crowd from their district. Peggy wouldn’t be sick, and they might have had a bit of stew and a piece of bread each day. Had she made the wrong choice and cost them all their lives? She felt so depressed and downhearted. Maybe they could still go to a workhouse. There was bound to be one somewhere around. They might get help there. The idea burned in her brain. She couldn’t leave Peggy, but Michael – he could go, maybe, and someone might come to help them with Peggy.

CHAPTER 14

Michael’s Desperate Search

MICHAEL SET OFF ACROSS THE FIELDS

. He had stockpiled enough fuel to keep the fire going. He felt frightened and strange on his own, but knew that Eily should stay with Peggy. Eily had hugged him close when he was leaving, and further on he turned back for a last look, wondering would he ever see his two sisters again. He knew basically which direction to take. He hoped he might meet someone along the road who would tell him the way to the workhouse.

He walked for over an hour and a half without seeing a sinner, then at the end of a small boreen he noticed a curl of smoke coming from a

broken-down old cabin. He made his way to it and hammered against the door. No one replied. He remembered the trick he had played when they were left on their own in the cottage and how scared they had been.

‘I don’t want to come in, don’t worry. I just want directions. Is the town of Castletaggart anywhere near here?’

There was no reply, so he repeated the question.

A deep husky voice answered. ‘It’s a good two to three days’ walk for tired legs and feet.’

‘Is there a workhouse roundabouts, then?’ begged Michael.

The old man inside considered before he spoke. ‘I heard that the O’Leary mill had been turned into a workhouse. It’s about a half-day from here. You keep to the main road and turn off at the bridge over the running river, then right, and you can’t help but see it.’ Then, as an afterthought, the voice added, ‘But I’d prefer to die in my own bed and not with strangers.’

‘Thank you,’ said Michael, starting to move off.

‘God spare you, lad, and keep you from all harm.’

Michael felt sad for the old man all alone in the world with no one to look after him.

He kept walking on. Two or three times he felt

dizzy and lightheaded and had to sit down to get his breath back. He could hear the river water running, but still could not see it. Then up ahead he was able to make out the crossroads and the humpy bridge. Two women lay on the ground near the bridge. They were both so weak they didn’t notice the young boy pass them.

Michael could not believe it when he came to the old mill. Crowds of people were waiting, sleeping on the cobblestones. They could go no further. A few of them were grouped together in families. They lay in their rags or blankets, relieved not to be on their own. From within the building came a constant moaning and crying, and a smell of disease and sickness seemed to fill the air around the place. Some people were praying out loud.

A nun, dressed in full habit, came through a small wooden door. She spoke in a loud voice: ‘This place is full. We have no space for man, woman or child, nor is there spare food. Perhaps by tomorrow when we have removed those who have died of sickness and the fever, we may be able to take a few.’

A murmur ran through the crowd and the women began to wail and cry. They had no place left to go, here was as good a place to die as anywhere else. At least they might get a blessing

said over them.

Michael began to run – he did not know where the energy came from – down past the bridge and back the way he had come. Tears coursed down his face. He could feel a pain in his chest and knew that his heart was broken in two and his childhood gone forever. He slowed down, he had a long and miserable way to go. There was no God, and if there was he was a monster.

Eily kept watching Peggy. She thrashed and moaned and cried for Mother again and again. Eily gave her more of the medicine and couldn’t help but notice that the jar was nearly empty. She herself was exhausted too. Nothing she could say or do would help Peggy now. She put her arms around her and kissed her little button nose and the freckles on her cheeks. The skin felt cooler to the touch. Within half an hour Peggy was freezing. Despite an extra blanket, shivers ran though her body and her teeth chattered.

Eily got in under the blankets with her, trying to keep her warm. The day itself was bright and sunny with just a soft breeze blowing. Eily hugged her close. She was only the weight of a baby. Eily rubbed each limb, trying to still the shivering and

shaking.

‘I’m here, Peggy. I’m here, Peggy,’ she kept whispering, not sure if her little sister could even hear her.

At last the shivering and chattering teeth began to still. Peggy’s body seemed more relaxed, her breathing quieter. She slept in the comfort of Eily’s arms, her head on her chest.

Eily looked up through the hawthorn tree. Its heavy branches moved softly in the breeze, the blue sky peeping through. Eily thought she noticed a blackbird up above, hiding among the foliage. Her eyes felt heavy and before she knew it, she was asleep.

Michael walked slowly. There was no rush now that he had nothing to bring back. He crossed a low broken-down stone wall. He could smell some wild garlic, and he rooted until he found it and put some in his pocket. One more wall and field to cross before he would be safely back with the girls.

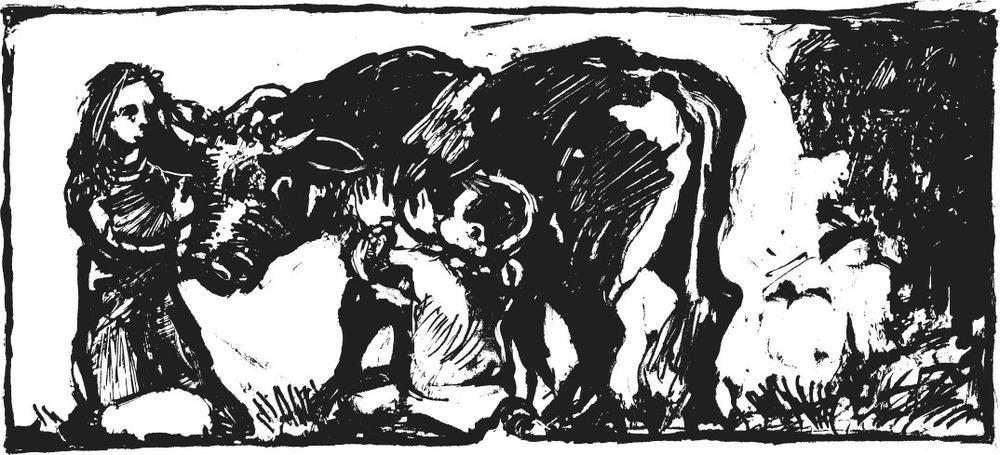

Gradually Michael became aware of the sound of mooing. A cow had tried to get in over a ditch and her two legs had got caught in a large pile of brambles and thorns. They were embedded into her pale brown-and-white skin. Michael hated to see an

animal in distress or pain and his first instinct was to help. He had passed a field with about twenty cows in it over a mile back and noticed the cowherd asleep on the grass. This cow must have strayed from there. Suddenly he got an idea. He took to his heels and ran, hell for leather.

‘Eily! Eily! Get up, quick. Come on, we’ve no time to lose,’ Michael shouted.

Eily stretched. Peggy was snoring gently. She lowered Peggy’s head down on the blanket. She rubbed her eyes. The sun was going down. It was nearly dusk. She must have been asleep for hours.

‘Eily, will you come on. We only have a bit of a chance. Get the blade and the water can.’ He had already begun to run back through the weeds and grass.

Eily dropped a few twigs on the fire which had nearly gone out, picked up the blade and can and followed him.

CHAPTER 15

The Cow

‘

WAIT, MICHAEL! WHAT IS IT

? Where are we going?’ she shouted.

He turned back and signalled her to be quiet. Within a minute he had led her to the ditch where the cow stood, still trapped.

Eily looked puzzled. Surely he wasn’t going to try and kill the cow. She patted her on the rump. The cow looked around balefully, her liquid brown eyes soft and gentle but yet afraid.

‘Keep a look-out for a minute,’ urged Michael.

She let her eyes roam around but couldn’t see anything move.

‘What are you going to do?’ she hissed.

‘I’m going to bleed her,’ he replied.

‘What?’ said Eily. ‘But you don’t know how to, Michael.’

‘I heard Father tell us stories often enough about times before the potatoes failed and he and his father bled the landlord’s cattle. Come here and give me a hand.’

He was patting the cow on the neck and rubbing his hand down her front and side to find a vein. His father had told him that if you hit the main vein by mistake, the animal would bleed to death in a few minutes. He searched around until he found a likely one. Eily passed him the blade. He made a nick in the finer skin under the neck, but nothing happened. He deepened the cut and a droplet or two of blood appeared. The cow lowed and rolled her frightened eyes.

‘Easy girl, easy,’ assured Eily, patting her and trying to calm her. Michael was squeezing at the opening with his fingers. The blood began to trickle and then to flow freely and spatter on the ground. Eily held the can to catch it as it fell. The blood seemed to pump quicker and quicker and in a little while the can was nearly full. Michael then made Eily put pressure on the vein and hold it to stop the bleeding while he mixed a paste of clay and grass

and spit and smeared it on the cut. It took about ten minutes before it slowed down to a slight seepage. The animal was baffled. They helped to tear the brambles and thorns from her legs and pull her out of the ditch, and then they led her back into the field. Michael knew it would only be a matter of time before the cowherd would come searching for her.

They couldn’t believe it when, about five minutes later, they heard the young man calling the cow. Although they were a good distance away, they were terrified and lay down in the long grass, hoping they were well hidden. Eily kept a good hold of the precious can. They did not dare to stir for about twenty minutes, then they got back to Peggy as quickly as they could.

She was still dozing peacefully. Her skin and temperature felt more normal to the touch.

‘Well, Michael, what about the workhouse? Is it far? Will we be able to get help for Peggy?’ Eily kept on with a barrage of questions.