UMBERTO ECO : THE PRAGUE CEMETERY (51 page)

Read UMBERTO ECO : THE PRAGUE CEMETERY Online

Authors: Umberto Eco

Simonini didn't ask how the Statistics Department knew of his skills. They may have heard from Hébuterne. He thanked Esterhazy for the compliment and said, "I imagine I'll have to reproduce the handwriting of a particular person."

"We have already identified the perfect candidate. His name is Captain Dreyfus, from Alsace of course. He is working for the department as a trainee. He's married to a rich woman and fancies himself a

tombeur de femmes,

so his colleagues can hardly bear him and wouldn't find him any better if he were Christian. He'll arouse no feelings of solidarity. He's an excellent sacrificial victim. After the document is received, investigations will be made and Dreyfus's handwriting will be recognized. After that it will be up to people like Drumont to whip up public scandal, expose the Jewish peril and at the same time save the honor of the armed forces that have so masterfully uncovered and dealt with it. Clear?"

Perfectly clear. In early October Simonini found himself in the presence of Lieutenant Colonel Sandherr, an ashen-faced man with insignificant features — the proper physiognomy for the head of an espionage and counterespionage service.

"Here we have an example of Dreyfus's handwriting, and here is the text to transcribe," said Sandherr, passing him two sheets of paper. "As you see, the note must be addressed to the military attaché at the embassy, von Schwarzkoppen, and must announce the arrival of military papers on the hydraulic brake for the 120-millimeter gun, and other details of that kind. The Germans are desperate for information like this."

"After that it will be up to people like Drumont to

whip up public scandal."

"Might it be appropriate to include some technical detail?" asked Simonini. "It would look more compromising."

"I hope you realize," said Sandherr, "once the scandal has erupted, this

bordereau

will become public property. We cannot let the newspapers have technical information. So down to business, Captain Simonini. For your convenience I have prepared a room with all the necessary writing materials. The paper, pen and ink are those used in these offices. I want it well done. You may take aslong and try as many times as you wish, until the handwriting is perfect."

And that is what Simonini did. The

bordereau,

written on onionskin paper, was a document of thirty lines, eighteen on one side and twelve on the other. Simonini had taken care to ensure that the lines of the first page were wider apart than those of the second, where the handwriting looked more hurried, since this is what happens when a letter is written in a state of agitation — it is more relaxed at the beginning and then accelerates. He had also taken into account that a document of this kind, if it is thrown away, is first torn up and would therefore reach the Statistics Department in several pieces before being reassembled, and so it would be better to space out the letter, to assist the

collage,

without straying too far from the writing he had been given.

All in all, he had done a good job.

Sandherr then had the

bordereau

sent to the minister of war, General Mercier, and at the same time ordered an examination of all documents circulated by all officials in the department. In the end his staff informed him that the handwriting was that of Dreyfus, who was arrested on the 15th of October. The news was carefully kept secret for two weeks, with just a few details allowed to leak out in order to whet the curiosity of journalists. Then a name began to circulate, first in strictest secrecy, and finally it was admitted that the guilty man was Captain Dreyfus.

As soon as Esterhazy had been authorized by Sandherr, he immediately told Drumont, who ran through the rooms of the newspaper office waving the major's message and shouting, "The evidence, the evidence, here's the evidence!"

On the 1st of November

La Libre Parole

ran the headline in block capitals: HIGH TREASON: ARREST OF THE JEWISH OFFICER DREYFUS. The campaign had begun. The whole of France burned with indignation.

That same morning, while the newspaper office was celebrating the happy event, Simonini's eye fell on the letter with which Esterhazy had given the news of Dreyfus's arrest. It was still on Drumont's desk, stained by his wine glass but completely legible. And to Simonini, who had spent more than an hour imitating what was supposed to be Dreyfus's handwriting, it seemed as clear as day that the handwriting on which he had worked so carefully was similar in every respect to that of Esterhazy. No one is more aware of such matters than a forger.

What had happened? Had Sandherr given him a piece of paper written by Esterhazy instead of one written by Dreyfus? Was that possible? Bizarre, inexplicable, but irrefutable. Had he done so by mistake? On purpose? But if so, why? Or had Sandherr been misled by one of his staff who had taken the wrong piece of paper? If Sandherr had been acting in good faith, he should be told of the mistake. But if Sandherr was acting in bad faith, it would be risky for Simonini to reveal that he knew the game Sandherr was playing. Inform Esterhazy? But if Sandherr had swapped the handwriting on purpose so as to harm Esterhazy, then if Simonini went to inform the victim, he would have the whole secret service against him. Keep quiet? And what if the secret service were one day to accuse him of carrying out the swap?

Simonini wasn't to blame for the error. He wanted to make sure this was clear, and above all that his forgery was, so to speak, genuine. He decided to take the risk and went to see Sandherr, who seemed reluctant to talk to him at first, perhaps because he feared an attempt at blackmail.

But when Simonini explained the truth (the only truth in what was otherwise a pack of lies), Sandherr, more ashen-faced than usual, appeared not to want to believe it.

"Colonel," Simonini said, "surely you have kept a photographic copy of the

bordereau.

Take a sample of Dreyfus's writing and one of Esterhazy's, and let us compare the three texts."

Sandherr gave an order, and after a short while there were three sheets of paper on the desk. Simonini made several observations: "Look here, for example. In all the words with a double ess, such as

adresse

or

intéressant,

in Esterhazy's hand the first of the esses is smaller and the second larger, and they are never joined up. This is what I noticed this morning, because I was particularly careful about this detail when I wrote the

bordereau.

Now look at Dreyfus's handwriting — this is the first time I've seen it. Astonishing! The larger of the two esses is the first, and the second is small, and they are always joined up. Shall I continue?"

"No, that's enough. I have no idea how this mistake has happened. I'll investigate. The problem now is that the document is in the hands of General Mercier, who can always compare it with a sample of Dreyfus's writing. But he's not a handwriting expert, and there are also many similarities between these two hands. We simply have to make sure it doesn't occur to him to look for a sample of Esterhazy's handwriting, though I don't see why he should even think of Esterhazy — providing you keep quiet. Try to forget all about this business, and I ask you not to return to these offices. Your payment will be adjusted accordingly."

From then on, Simonini didn't need to rely on confidential information to find out what was happening, since the newspapers were full of the Dreyfus affair. Some people, even at military headquarters, were acting with caution, asking for clear proof that the

bordereau

was by Dreyfus. Sandherr sought the opinion of the famous handwriting expert Bertillon, who confirmed that the calligraphy in the

bordereau

was not exactly the same as Dreyfus's, but, he stated, it was a clear case of self-falsification — Dreyfus had slightly altered his own writing so it would be thought to be the writing of someone else. Despite these tiny details, the document was certainly written by Dreyfus.

Who would have dared to doubt it, especially when

La Libre Parole

was bombarding public opinion every day and raising the suspicion that the

affaire

would be hushed up, since Dreyfus was a Jew and would be protected by the Jews? "There are forty thousand officers in the army," wrote Drumont. "Why on earth did Mercier entrust national defense secrets to a cosmopolitan Alsatian Jew?" Mercier was a liberal who had been under pressure for some time from both Drumont and the national press, who accused him of being a Jewish sympathizer. He could not be seen as the defender of a Jewish criminal. So he did nothing to impede the investigation, showing himself, on the contrary, to be pursuing it.

Drumont hammered on: "The Jews had long been kept out of the army, which had maintained its French purity. Now that they've infiltrated the nation's armed forces they will be masters of France, and Rothschild will direct their mobilization . . . And you understand to what ends."

Tensions had reached their height. The captain of the dragoons, Crémieu-Foa, wrote to Drumont telling him he was insulting all Jewish officers, and demanded satisfaction. The two of them fought a duel, and, to add to the confusion, whom did Crémieu-Foa choose as his second? Esterhazy. Then the Marquis de Morès, one of the editors of

La Libre Parole,

issued a challenge to Crémieu- Foa, but the captain's superiors refused to allow him to take part in another duel and confined him to barracks, so Captain Mayer took his place, and died of a perforated lung. Heated debates, protests against this rekindling of religious war . . . And Simonini sat back, contemplating with great satisfaction the cataclysmic results of his single hour's work as scribe.

The council of war met in December, and at the same time another document was produced, a letter to the Germans from Panizzardi, the Italian military attaché, which referred to "that coward D," who had sold the plans of various fortifications. Did the "D" stand for Dreyfus? No one dared doubt it, and only later was it discovered that it was a man called Dubois, an employee at the ministry, who had been selling information at ten francs apiece. Too late. Dreyfus was found guilty on the 22nd of December, and in early January was stripped of his rank at the École Militaire. In February he would sail for Devil's Island.

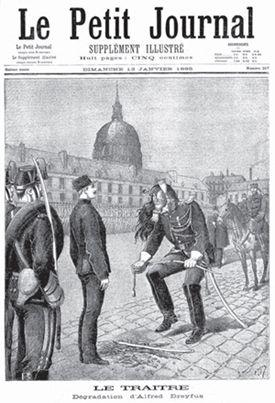

Simonini went to watch the degradation ceremony, which he describes in his diary as being extraordinarily dramatic. The troops were lined up around the four sides of the courtyard. Dreyfus arrived and had to walk for almost a kilometer between the lines of valiant men who, though impassive, managed to express their contempt for him. General Darras drew his saber, a fanfare sounded, Dreyfus marched in full uniform toward the general, escorted by four artillerymen under the command of a sergeant. Darras pronounced the sentence of degradation. A giant of a gendarme officer in a plumed helmet approached the captain, ripped off his stripes and buttons and regimental number, removed his saber and broke it over his knee, throwing the two halves to the ground in front of the traitor.

Dreyfus appeared impassive, and this was taken by many newspapers as a sign of his treachery. Simonini thought he heard him shout "I am innocent!" at the moment of the degradation, but in a dignified manner, still standing at attention. It was as if, Simonini observed sarcastically, the little Jew identified so closely with the (usurped) dignity of his role as a French officer that he was unable to question the decisions of his superiors — as if, since they had decided he was a traitor, he had to accept the matter, not allowing any doubt to cross his mind. Perhaps he really felt he was a traitor, and the declaration of innocence was, for him, just a necessary part of the ritual.

A giant of a gendarme officer in a plumed helmet approached

the captain, ripped off his stripes and buttons and regimental

number, removed his saber and broke it over his knee, throwing t

he two halves to the ground in front of the traitor.