UMBERTO ECO : THE PRAGUE CEMETERY (22 page)

Read UMBERTO ECO : THE PRAGUE CEMETERY Online

Authors: Umberto Eco

At this point Dalla Piccola's account is also fairly sketchy and incomplete, as if he too were having difficulty recalling what his counterpart was constrained to forget.

It seems, however, that having returned to Sicily at the end of September, Simonini remained there until March of the following year, trying unsuccessfully to get his hands on Nievo's accounts and receiving a fortnightly dispatch from Cavalier Bianco asking with a certain impatience how far he had progressed.

Nievo was now dedicating body and soul to those confounded accounts, increasingly worried about malicious rumors, expending more and more energy investigating, examining, scrutinizing thousands of receipts so as to be sure of what he was recording. He had been given considerable authority, since Garibaldi was also anxious not to create scandal and gossip, and had arranged for him to have an office with four assistants and two guards at the entrance and on the stairways so that no one could, so to speak, enter its con- fines at night in search of the accounts.

Indeed, Nievo had let it be known that he suspected someone might not be happy about what they contained. He feared the accounts might be stolen or tampered with and had therefore done his best to ensure they were impossible to find. And all Simonini could do was consolidate his friendship with the poet, with whom he was now on more informal terms, so as to understand what he planned to do with those wretched books.

They spent many evenings together, in an autumnal Palermo that still languished in heat untempered by the sea breezes, sipping an occasional water and anisette, allowing the liqueur to diffuse gradually in the water like a cloud of smoke. Little by little, Nievo abandoned his military reserve and came to trust Simonini, perhaps because he liked him, perhaps because he felt himself to be a prisoner in the city and needed the company of someone else with whom he could daydream. He talked about a love he had left behind in Milan, an impossible love, because her husband was not only his cousin but also his best friend. Nothing could be done about it. Other loves had already driven him to hypochondria.

"That's how I am, and how I'm condemned to remain. I will always be a moody, dark, somber, irritable individual. I'm now thirty and have always fought wars to distract me from a world I do not love. And so I've left a great novel at home, still in manuscript. I'd like to get it printed, but can't because I have these bloody accounts to look after. If I were ambitious, if I thirsted for pleasure . . . if I were at least bad . . . At least like Bixio. Never mind. I'm still a child, I live one day at a time, I love the excitement of rebellion, the air I breathe. I'll die for the sake of dying . . . And then it will all be over."

Simonini did not try to console him. He considered him incurable.

In early October there was the battle of Volturno, where Garibaldi fought off the Bourbon army's last offensive. During that same period, General Cialdini had defeated the papal army at Castelfidardo and invaded Abruzzo and Molise, formerly part of the Bourbon kingdom. At Palermo, Nievo was frustrated. He had heard that among his accusers in Piedmont were followers of La Farina, who was apparently speaking ill of anyone connected with the Redshirts.

"It makes you want to give up," said Nievo, dejected, "but it's exactly at moments like this that we mustn't abandon the helm."

On the 26th of October the great event took place: Garibaldi met Vittorio Emanuele at Teano. The general practically handed over southern Italy. For this, said Nievo, he should at least have been appointed a senator. And yet, at the beginning of November, Garibaldi lined up fourteen thousand men and three hundred horses at Caserta and waited for the king to come and review them, and the king never appeared.

On the 7th of November, the king made his triumphal entry into Naples, but Garibaldi, a modern-day Cincinnatus, withdrew to the island of Caprera. "What a man," said Nievo. And he cried, as poets do (which greatly irritated Simonini).

A few days later, Garibaldi's army was disbanded. Twenty thousand volunteers were accepted into the Savoy army, but so too were three thousand Bourbon officers.

"That's fair, they're Italians too," said Nievo. "But it's a sad ending to our epic campaign. I'm not signing up. I'll take six months' pay, then goodbye. Six months to complete my job — I hope I'll manage it."

It must have been a dreadful job. By the end of November he had barely completed the accounts to the end of July. At a rough guess, another three months were needed, perhaps more.

When Vittorio Emanuele reached Palermo in December, Nievo told Simonini: "I'm the last Redshirt down here and I'm looked upon as a savage. What's more, I have to answer the slanders of La Farina's lot. Good Lord, if I knew it would end like this, instead of leaving Genoa for this prison I'd have drowned myself and been better off."

Simonini had still not found a way of laying his hands on those wretched accounts. Then all of a sudden, in mid-December, Nievo announced he was returning to Milan for a short visit. Leaving the accounts in Palermo? Taking them with him? It was impossible to know.

Nievo planned to be away for almost two months, and Simonini tried to make use of that bleak period by visiting the area around Palermo. (I'm no romantic, he thought, but what is Christmas in a snowless desert strewn with prickly pears?) He bought a mule, put on Father Bergamaschi's cassock and went from town to town listening to the gossip of curates and farmers, but also uncovering the secrets of Sicilian cooking.

In secluded country inns he came across excellent rustic delicacies that cost little, including

acqua cotta:

all you had to do was put slices of bread in a tureen and dress them with plenty of olive oil and freshly ground pepper; then you boil chopped onions, peeled sliced tomatoes and wild mint in three quarters of a liter of water; after twenty minutes, pour this over the bread in the tureen and allow it to rest for a few minutes, then serve it hot.

On the outskirts of Bagheria he found an inn with a few tables in a dark hall. In that pleasant shade, welcoming even during the winter months, a landlord of grubby appearance prepared wonderful offal dishes such as stuffed heart, pork brawn, sweetbreads and every type of tripe.

There he met two characters, each quite different from the other. Only later, by a stroke of genius, was he able to bring them together as part of a single plan. But let us not rush ahead.

The first seemed half mad. The landlord said he gave him food and lodging out of pity, though the man was actually able to perform many useful chores. Everyone called him Bronte, and in fact it seems he had escaped from the Bronte massacres. He was continually haunted by memories of the rebellion and after a few glasses of wine would bang his fist on the table and shout in thick dialect, which might roughly be translated as: "You masters beware, the hour of judgment is at hand! Fear not, citizens, be ready!" This was what his friend Nunzio Ciraldo Fraiunco, one of the four men later executed by Bixio, had shouted before the insurrection.

Bronte wasn't particularly intelligent, but at least he had one fixed idea. He wanted to kill Nino Bixio.

Bronte was, for Simonini, just a simpleton with whom he could pass a few winter evenings. Of more immediate interest was another figure, a hirsute man who at first kept to himself, but when he heard Simonini asking the landlord about the recipes for various dishes, he joined the conversation and turned out to be a fellow gastronome. Simonini told him how to make

agnolotti alla piemontese,

while he revealed the secrets of

caponata;

Simonini described

tartare all'albese

until his mouth watered, and he expounded on the alchemy of marzipan.

This man, Master Ninuzzo, spoke something approaching Italian, and hinted that he'd also traveled abroad. And then, after describing his great devotion to the various effigies in the local sanctuaries, and expressing his respect for Simonini's ecclesiastical dignity, Ninuzzo confessed his curious situation. He had been an explosives expert with the Bourbon army — not an ordinary soldier but the keeper of a nearby powder magazine. Garibaldi's men had driven back the Bourbon army and seized the munitions and powder, but instead of dismantling the bunker, they'd kept Ninuzzo in their service to guard the place, in the pay of the military authorities. And there he was, getting bored, awaiting orders, resentful of the northern occupiers, faithful to his king, dreaming of rebellion and insurrection.

"I could blow up half of Palermo if I wanted to," Ninuzzo whispered, as soon as he understood that neither was Simonini on the side of the Piedmontese. And he described how, to his amazement, the usurpers had failed to realize that beneath the magazine was a vault containing more kegs of gunpowder, grenades and other weaponry. These were to be kept for the imminent counterattack, seeing that resistance groups were organizing themselves in the hills to make life difficult for the Piedmontese invaders.

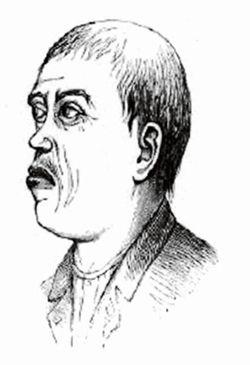

Everyone called him Bronte, and in fact it seems

he had escaped from the Bronte massacres.

His face gradually lit up as he talked about explosives, and his pug-nosed features and gloomy eyes became almost handsome. Then one day he took Simonini to his bunker and, reappearing from an exploration of the vault, showed him some blackish granules in the palm of his hand.

"Ah, most reverend Father," Ninuzzo said, "there's nothing more beautiful than fine-quality powder. Look at that slate-gray color. The granules don't crumble when pressed between the fingers. If you had a piece of paper and put the powder on it and ignited it, it would burn without touching the paper. They used to make it with seventy-five parts of saltpeter, twelve of charcoal and twelve of sulfur. Then they moved on to what they called the English blend, which was fifteen parts charcoal and ten of sulfur, and that's how you lose wars, because your grenades don't explode. Today we experts (though unfortunately, or thank God, there are few of us) use Chilean nitrate instead of saltpeter, and that's quite another thing."

"Better?"

"It's the best. You see, Father, they're inventing new explosives every day, and each is worse than the other. One of the king's officials (by which I mean the real king) appeared to know everything and told me I should use a brand-new invention, pyroglycerine. He didn't understand that it only works on impact. It's difficult to detonate because you have to be there banging it with a hammer, and you'd be the first to blow up. Let me tell you, if you ever want to blow someone up, old-fashioned gunpowder's the only thing. And it makes a fine show."

Master Ninuzzo seemed overjoyed, as if there were nothing more beautiful in the world. At the time, Simonini didn't attach much importance to his ramblings. But later, in January, he thought about it again.

Mulling over ways of getting his hands on the expedition's account books, he reasoned as follows: Either the accounts are here in Palermo or they will be back in Palermo when Nievo returns from the north. Nievo will then have to take them back to Turin by sea. Therefore it's pointless to follow him night and day, as that won't get me near the secret safe, and even if I do get near the safe, I won't be able to open it. If I did get there and open it, there'd be a scandal, Nievo would report the disappearance of the accounts, and my masters in Turin might be blamed. Nor could I keep the matter quiet even if I surprised Nievo with the accounts and knifed him in the back. The dead body of someone like Nievo would always be a cause for embarrassment. They told me in Turin that the accounts had to go up in smoke. But Nievo ought to go up in smoke with them, so when he disappears (in a way that seems accidental and natural), the disappearance of the accounts will fade into the background. Therefore, why not burn down or blow up the revenue offices? Too obvious. The only other solution is for Nievo to disappear, along with his accounts, while he's sailing from Palermo to Turin. If fifty or sixty people lost their lives in a disaster at sea, nobody would think it was done to destroy a few scruffy account books.