Two Rings (14 page)

Authors: Millie Werber

The officers of the SD wore black uniforms, and everyone was petrified of them.

We were led through the main floor of the building and then down a flight of stairs. It was dark in the stairwell, and it was hard to see the steps as we descended. It began to seem that we were no longer in a building at all but rather going down under the earth. It smelled like the earthâa musty smell of moisture and dirtâa smell fit for animals.

At the bottom of the stairs, down a little ways, there was a room, though “room” is not really the right word for this place. It was like a dungeon dug out from the ground: The floor was just packed earth; there were no windows. There was a small, dim bulb hanging from the ceiling. It was the jail of the SD.

We were perhaps twenty-five people in this room, this dungeon. Eight or ten of the group were those rounded up in Miller's Rassenschande affair. The girl Greenspan was thereâthe one who had been caught kissing her boyfriend, the one on whose account Kunah had decided to arrest me.

Really, I was there because of her. I know this is not an entirely fair assessment: She had done nothing to cause my arrestâmy arrest was through no fault of hersâbut I was there because my cousin had brought me because I had the same name as hers. If she hadn't been chosen by Miller, Kunah would never have taken me. But in this girl Greenspan's mind, in her fear, in her desperation at what was surely about to ensue, the whole situation was the other way around.

“I'm here because of you!” she screamed. “You're the one who got me here! You got me arrested!”

This was crazy, of course.

“No one knows me as Greenspan. There are no papers, no documents. I am Mania Drezner, as I have always been. I have nothing to do with this,” I kept protesting. But she wouldn't let go of it; she wouldn't listen to reason. She was just tormenting me with her accusations, unfounded, unreasonable, unending.

We were hours in that dungeon jail. It felt like years. Standing in the darkness, we could hear the screams from upstairs. Screams to make your bones sting. Screams that if there were

a God, God would hear; if there were a God, God would make those screams stop.

a God, God would hear; if there were a God, God would make those screams stop.

No light. No food. No water. No rescue. No God.

The hours droned on.

They came in, the SS, the SDâI don't know who they were. They came in and took us out, one at a time. One by one. And between their visits to our dungeon, only screams.

No light. No food. No water.

No bathrooms.

People had to go. People needed to urinate. But there was nowhere to go in that earthen dungeon, and people knew they could be shot for soiling the floor. We were petrified that our waste might make a noticeable stench that would get us killed.

An absurd fear befitting an absurd place: We were going to be killed anyway in this place, whether we relieved ourselves or not. But how to avoid urinating in jail now became our focus, the searing focal point of our agony and apprehension.

What the men did! I didn't want to look; I didn't want to see their desperation. The men tied their penises. They tore off strips from their shirts, pulled pieces of string from their pockets, to tie tourniquets around their penises so the urine couldn't come out. They moaned in double distress, each man in his own private misery, trying to hold it in.

Then I, too, had to go. At first just a quiet pressure, a tingling almost, in my lower abdomen. I was used to thisâwe all were. During our shifts in the celownik, we weren't allowed to go to the bathroom whenever we needed to. At the end of the first six-hour shift, we were given fifteen minutes: If we needed to go, that's when we were allowed. But if we had to go earlier,

then we just had to hold itâwe had to wait until the end of the shift.

then we just had to hold itâwe had to wait until the end of the shift.

The body grows accustomed to its circumstance: I learned to hold it in, as we all did. The pressure would come, it would draw my attention, and then it would subside. At least for a time. When it returned, it would be more insistent, almost a bright spot, a pulsing knot of nerves deep inside my groin. But I learned to hold it in, in the factory, knowing that at some point, my six hours would be up.

It was different in the jail. The screaming upstairs, the shrieks of people I knew, of people who had been standing with me in that dankness just before. Me. I am next; they're going to take me next; now is when I am going to die. And the people moaning beside me, suffering in their own extremities of body and spirit, privately, miserably.

I thought I would burst. Not figuratively; this is not a way of speaking: I thought my bladder was going to rupture inside of me.

And then Zosia came to me. Zosiaâan angelâthe first of two that visited me that day.

Zosia Smuzik was a beautiful woman. Tall and strong, with pure white hair and high cheekbones. She didn't look Jewish; she looked Aryan, almostâand she spoke German flawlessly. I had known her a little from the kitchen, and we slept in the same barracks. I remember thinking how elegant she was, and confident, even in the extremity of our circumstances. Sometimesâwhere did she find the courage for this?âshe would stand up to the Germans. Once, I heard her say to a German officer, “You want the Jews to work? Then you must feed them! They cannot work if they are weak from starvation!” Why was she not killed for these small acts of defiance?

Perhaps the Germans thought she was a Jewish sympathizer rather than a Jew. Perhaps that was why she wound up in the same jail as the rest of us; I don't know. Surely she hadn't been involved in the Rassenschande affair; she was a grown woman already, perhaps fifty or more. Were the Germans simply amused by her? By the absurdity of her belief that her insistence could make a difference?

Perhaps the Germans thought she was a Jewish sympathizer rather than a Jew. Perhaps that was why she wound up in the same jail as the rest of us; I don't know. Surely she hadn't been involved in the Rassenschande affair; she was a grown woman already, perhaps fifty or more. Were the Germans simply amused by her? By the absurdity of her belief that her insistence could make a difference?

I don't know. Perhaps it doesn't matter what she was to the Germans; I know what she was to us, to me.

Zosia saw that I was suffering, struggling to accomplish what physically was impossibleâto keep myself from urinating. She came to me, removed the sweater she was wearing under her striped uniform, rolled it up in a tight ball, and held it out to me. She whispered, “Take off whatever you're wearing underneath and use this.” It took me a moment to understand what she was suggesting, what she was offering. It was not as if she had sweaters to spare, as if she could throw this one away to be soiled by my urine and then easily slip into another to keep warm. Who knew how long we would be held in this jail? Who knew how long to shiver in the dark? She didn't know; it seems she didn't care. She saw my struggle; she wanted to give me ease; she wanted to give me her sweater.

I took it. I removed my underwear. I urinated into the warm ball of wool.

Then she drew us near, all of us. “Come,” she said. “Come, my children; come to me. I want to tell you a story.” Like a mother gathering her young, preparing her children for bed, Zosia called us to her. I couldn't be called a childâI was sixteen at the time, already a married womanâand everyone else in that jail was older than I. But Zosia had asked us to come; she had invited us into the embrace of her wisdom, and we

drew ourselves to her as to the warmth and light of a household hearth.

drew ourselves to her as to the warmth and light of a household hearth.

“My children,” she said, “we are going to die here. This is true. But when we are shot in this horrible place, we will go straight up to Heaven. And you will see when you come up, you will see that the angels will be there, waiting for us.”

She was speaking to grown people, to men and women who hadn't heard bedtime stories in decades, to men and women not given to fantasies of Heaven and angels. And yet. And yet. We listened, hungry, starving for her words.

“You will see, my children, that there will be long tables with white tablecloths. And all the tables will be piled high with foods of every sort you can imagineâoranges and pineapples and meats and cheese and bread still warm from the fire. And the angels will be happy for us, happy to see us there with them, and they will dance around us and cheer our arrival into their midst.”

This was bliss; this was sublimeâto lose ourselves for some moments, some minutes, in the midst of that awful place. We listened to her speak, and for those minutes, I was no longer in that jail, no longer clutched by fear. What a gift she gave us! What a godsend. I didn't care if what she said was foolishness; in those moments, it was real to me, and I was willing for her words to be more real, more true, than the crushing truth I saw around me. Her vision offered me light and hope and freedom, and I was more than ready to make her vision mine. I never forgot the feeling of those few moments of relief. It was a foretaste of Heaven, whatever Heaven might be.

Â

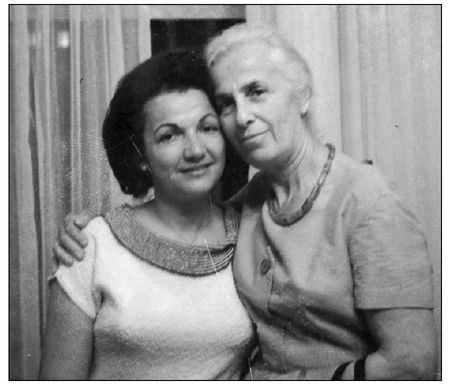

Zosia and me in the 1960s

Zosia survived her time in the SD jail, one of the very few who did. She survived the war, as well. We found each other, years later. She was living in Israel, in a small town called Pardes Hannah. She had aged, of course, since the last time I had seen her, but she still had that self-possessed elegance I so admired. Jack and I would visit her whenever we traveled to Israel, and we would always bring small packages of food with us, filling them with canned tuna and coffee and jamsâanything we thought might have been hard to find in Israel in those days. I always wanted to be giving Zosia somethingâeven little things. She had given me so much.

Once during a visit, I asked what possessed her that day in the jail, what had brought to mind the idea of telling us this story about Heaven and angels and a feast we couldn't possibly

enjoy. She told me then about a movie she had seen, a Polish movie, I think, in which a man was jailed for some terrible crime and was awaiting execution. The man was suffering from fear, awaiting his end. His jailer, noticing his agony, took pity on him and looked around for someone to visit him, to talk with him, to ease his sense of doom. But search as he might, the jailer was unable to find anyone who would agree to visit this criminal, until he found a prostitute, a woman already shamed, already beaten down by the world, and unable to hold herself in higher regard than a convict. This woman came to the jail and sat with the man for some time. She told him a story, of Heaven and angels and tables overflowing with food. And he sat and listened to her, rapt in her imaginings, and for that time, his heart was eased, his fears diminished. Zosia had thought of this movie when we were huddled together in that jail. Though we were not criminals, though she was not a prostitute, we were all there, rejected by the world, with no one to offer us comfort in what we were sure would beâand what for many of us wasâour final hours. So Zosia thought to comfort us with the story line of a movie she had seen, and her little plan worked. For me, I can say, it worked.

enjoy. She told me then about a movie she had seen, a Polish movie, I think, in which a man was jailed for some terrible crime and was awaiting execution. The man was suffering from fear, awaiting his end. His jailer, noticing his agony, took pity on him and looked around for someone to visit him, to talk with him, to ease his sense of doom. But search as he might, the jailer was unable to find anyone who would agree to visit this criminal, until he found a prostitute, a woman already shamed, already beaten down by the world, and unable to hold herself in higher regard than a convict. This woman came to the jail and sat with the man for some time. She told him a story, of Heaven and angels and tables overflowing with food. And he sat and listened to her, rapt in her imaginings, and for that time, his heart was eased, his fears diminished. Zosia had thought of this movie when we were huddled together in that jail. Though we were not criminals, though she was not a prostitute, we were all there, rejected by the world, with no one to offer us comfort in what we were sure would beâand what for many of us wasâour final hours. So Zosia thought to comfort us with the story line of a movie she had seen, and her little plan worked. For me, I can say, it worked.

But, then, truly, for how long could it work? Like waking from a dream, like opening my eyes again from the silken warmth of a midnight sleep into the air of a frigid room in winter, we roused ourselves from Zosia's reverie and returned again to the desolation of our jail. Still we were there below the SD head-quarters.

There was still the endless wait for a soldier to come and call our names, still the screams, still the desperation.

There was still the endless wait for a soldier to come and call our names, still the screams, still the desperation.

Other books

The Beekeeper's Ball: Bella Vista Chronicles Book 2 by Susan Wiggs

An Evil Cradling by Brian Keenan

Sunset Rising (Sunset Vampire Series, Book 5) by Jaz Primo

Ugley Business by Kate Johnson

The Willful Princess and the Piebald Prince by Robin Hobb

One Scream Away by Kate Brady

Tempt Me Eternally by Gena Showalter

Secondhand Purses by Butts, Elizabeth

The Clay Dreaming by Ed Hillyer

Divided Allegiance by Moon, Elizabeth