Trouble in July (19 page)

Authors: Erskine Caldwell

“The only thing to do now is send the coroner out here,” Jeff said sadly. “There ain’t a thing we can do now, son.”

Bert caught his arm.

“Maybe we’d better take down a few names,” he said, “in case Judge Ben Allen want to have a case made out.”

Jeff was startled.

“No,” he said firmly. “I don’t want to get mixed up in this thing politically. The people—”

“But—”

Jeff went towards the car, leaving Bert in the bushes. In a few moments he heard Bert calling him in a loud whisper.

“Come here quick, Sheriff Jeff,” he called.

Jeff went back to see what he wanted with him.

“Look!” Bert pointed in the opposite direction, downstream.

Katy Barlow was wading through the branch from the other side. None of the men around the tree had seen her then, but she was already less than a dozen yards from them. Then she stopped and looked up at the body of Sonny as it turned slowly on the rope.

“He didn’t do it!” she yelled at the top of her voice. The sudden burst of sound in the quiet woods echoed for almost a minute. She ran forward. “It was a lie! He didn’t do it!” She was screaming hysterically by the time she had finished.

Men who had gone as far as the bridge came running back to the tree. The ones who were already there stood as if

they

were in a trance.

Bert could hear Jeff swallow half a dozen times.

“Why don’t you believe me!” Katy cried, running from group to group and beating the men with her fists. “He didn’t do it! Nobody done it! It was a lie!”

The body on the rope stopped turning for a moment, and then it began to turn slowly in the opposite direction. Some of the men looked up at it, gazing upon it as though they had not seen it before.

“Nobody done it!” Katy screamed. She was disheveled and mud-stained, looking as if she had been struggling through the swamp all night. “It was a lie, I tell you!”

The men had gathered in a semicircle around her, almost shutting her from view. Neither Jeff nor Bert could see her for a while.

“Ask Leroy Luggit!” she cried. “He knows it’s a lie! Ask him! Leroy knows!”

She dashed to the tree from which the boy’s body hung. The men moved over the ground, keeping up with her.

“Why don’t you go find Leroy Luggit and ask him!” she cried hoarsely at the men. “He’ll tell you it was a lie! He knows! He knows! He knows!”

There was a period of silence everywhere in the woods. The only sounds Jeff and Bert could hear was the rasping noise in their own throats. The men began to move closer to the tree, and Jeff and Bert were able to see only glimpses of her between the moving bodies.

A piercing scream filled the woods. A roar of angry voices followed. A bluejay fluttered recklessly through the branches of a tree overhead and, screeching shrilly, disappeared in the direction of Earnshaw Ridge.

“What’s going on, Bert?” Jeff whispered, shaken.

“I can’t see a thing,” Bert said helplessly.

“If she’s in danger, we’ll have to protect her,” Jeff said, pausing. “But they wouldn’t harm her, would they, Bert?”

Bert hesitated, gripping a sapling in his hand.

“It don’t seem like they would,” he said. “Unless they’ve turned on—”

Jeff braced himself against the strongest of the young trees. Perspiration was dripping from his forehead and face.

Katy screamed again, but the sound was faint and weak. The men, as quickly as they had gathered, ran towards the bridge, pushing and cursing each other. For the first time Jeff and Bert saw stones flying through the air. Then, as one final fragment of rock hit her, she sank to the ground without a sound.

Jeff grabbed Bert by the arm, wavering on his feet. Neither of them could speak.

One of the men suddenly turned, ran back and heaved a heavy stone at Katy’s inert body. He raced to the bridge, looking back over his shoulder.

“Bert—” Jeff managed to say.

They moved through the bushes as the noisy sound of automobile motors crashed through the grove. Bert reached the tree long before Jeff could get there. He had fallen on his knees and lifted Katy and was holding her in his arms when Jeff stopped against the tree.

“Katy—” Bert said, holding her as tenderly as he could.

She opened her eyes and looked up at them through her matted raven hair. Bert brushed it away from her face.

A faint smile appeared on her lips.

“Tell Leroy—” she said feebly.

The smile faded away.

Bert laid her down on the pile of stones as gently as he could, and stood up, his eyes searching Jeff’s face.

“Sheriff Jeff, her head felt like—” he stopped, looking queerly at the older man. “Her head—”

Jeff nodded, turning his face away. He walked to the bank of the branch and stood looking at the water swirling under a fallen log.

When he turned and looked towards the tree, he saw Bert standing dazedly beside the girl’s body, while, above, the darker body turned slowly around and around on the end of the rope. Jeff drew his hand over his face, rubbing his burning eyes.

He left the branch where he had been standing.

“It ought to put an end to lynching the colored for all time,” he said, walking away.

Bert ran and caught up with him.

“What did you say, Sheriff Jeff?”

“Nothing, son,” he said a little more distinctly. “We got to hurry to town and make a report of this. The coroner will want to know about it. It’s his duty to inquire into the cause of deaths like this. He’ll want to know all about it in order to be able to perform his duty as he sees it, without fear or favor.”

He walked blindly towards the road.

“That’s a mighty pretty oath for a man in public office to swear to,” he said aloud. “I reckon I had sort of forgotten it.”

He walked ahead, alone.

Erskine Caldwell (1903–1987) was the author of twenty-five novels, numerous short stories, and a dozen nonfiction titles, most depicting the harsh realities of life in the American South during the Great Depression. His books have sold tens of millions of copies, with

God’s Little Acre

having sold more than fourteen million copies alone. Caldwell’s sometimes graphic realism and unabashedly political themes earned him the scorn of critics and censors early in his career, though by the end of his life he was acknowledged as a giant of American literature.

Caldwell was born in 1903 in Moreland, Georgia. His father was a traveling preacher, and his mother was a teacher. The Caldwell family lived in a number of Southern states throughout Erskine’s childhood. Caldwell’s tour of the South exposed him to cities and rural areas that would eventually serve as backdrops for his novels and stories. After high school, he briefly attended Erskine College in Due West, South Carolina, where he played football but did not earn a degree. He also took classes at the University of Virginia and the University of Pennsylvania. During this time, Caldwell began to develop the political sensibilities that would inform much of his writing. A deep concern for economic and social injustice, also partly influenced by his religious upbringing, would become a hallmark of Caldwell’s writing.

Much of Caldwell’s education came from working. In his twenties he played professional sports for a brief time, and was also a mill worker, cotton picker, and held a number of other blue collar jobs. Caldwell married his college sweetheart and the couple began having children. After the family settled in Maine in 1925, Caldwell began placing stories in magazines, eventually publishing his first story collection after F. Scott Fitzgerald recommended his writing to famed editor Maxwell Perkins.

Two early novels,

Tobacco Road

(1932) and

God’s Little Acre

(1933), made Caldwell famous, but this was not initially due to their literary merit. Both novels depict the South as beset by racism, ignorance, cruelty, and deep social inequalities. They also contain scenes of sex and violence that were graphic for the time. Both books were banned from public libraries and other venues, especially in the South. Caldwell was prosecuted for obscenity, though exonerated.

The 1930s and 1940s were an incredibly productive time for Caldwell. He published a number of novels and nonfiction works that brilliantly captured the tragedy of American life during the Depression years. His novels took an unflinching look at race and murder, as in

Trouble in July

(1940), religious hypocrisy, as in

Journeyman

(1935), and greed, as in

Georgia Boy

(1943). In 1937 he partnered with his second wife, Margaret Bourke-White, a photographer, to produce a nonfiction travelogue of the Depression-era South called

You Have Seen Their Faces

.

Through the decades, Caldwell continued to focus his attention on the dehumanizing force of poverty, whether in the South or overseas. Caldwell’s reputation as a novelist grew even as he pursued journalism and screenwriting for Hollywood. He adapted some of his best-known novels into screenplays, including

God’s Little Acre

and

Tobacco Road

, directed by John Ford. As a journalist, he worked as a war correspondent during World War II and wrote travel pieces from every corner of the globe. In 1965 he traveled through the South and wrote about the racial attitudes he encountered in his heralded

In Search of Bisco

.

Caldwell spent much of his later years traveling and writing while living with his fourth wife, Virginia, in Arizona. A lifelong smoker, Caldwell died of lung cancer in 1987.

A baby portrait of Erskine Caldwell. Born December 17, 1903, in White Oak, Georgia, to a Presbyterian minister and a schoolteacher, Caldwell would later describe his childhood home as “an isolated farm deep in the piney-woods country of the red clay hills of Coweta County, in middle Georgia.” (Image courtesy of Dartmouth College Library.)

Erskine Caldwell as a child. With a minister father, Caldwell spent many of his early years traveling the South’s numerous tobacco roads. During these years, he observed firsthand the trials of isolated rural life and the poverty of tenant farmers—themes he would later engage with in his novels. (Image courtesy of Dartmouth College Library.)

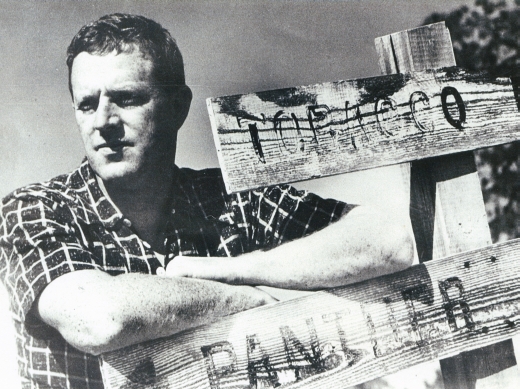

Caldwell’s early novels linked him forever to the Tobacco Road region of the South. This photograph, taken by Caldwell’s second wife, photographer Margaret Bourke-White, references the title of his most famous work,

Tobacco Road

. Published under legendary editor Maxwell Perkins in 1932, the novel was adapted by Jack Kirkland for Broadway, where the play ran for 3,182 performances from 1933–1941, making it the longest-running play in history at that time, and earning Caldwell royalties of $2,000 a week for nearly eight years. (Image courtesy of Dartmouth College Library.)