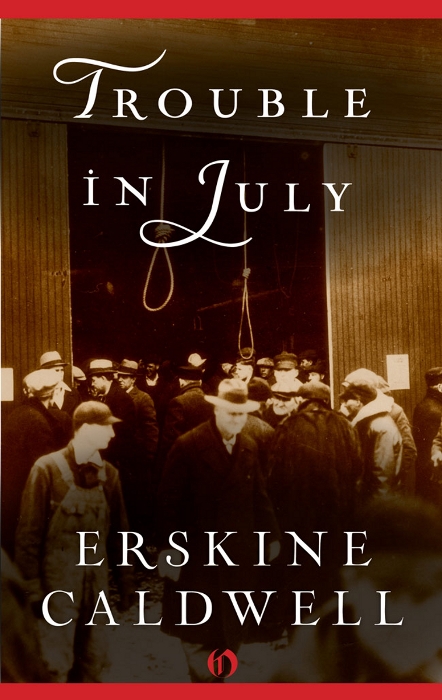

Trouble in July

Authors: Erskine Caldwell

Erskine Caldwell

A Biography of Erskine Caldwell

S

HERIFF

J

EFF

M

CCURTAIN

was sound asleep in bed with his wife on the top floor of the jailhouse in Andrewjones, the county seat, when the noise of somebody pounding on the door woke him up. He was a heavy sleeper, and only an unusually loud noise, or a shaking by his wife, ever made him wake up before daylight in the morning.

He and his wife lived in four comfortable rooms on the second story in the front section of the red-brick jailhouse. The rooms directly underneath on the first floor were offices, and behind them was a long barn-like room filled with ceiling-high prisoners’ cages. There was a heavy iron-grid door, and also a thick steel fire-door, between the two parts of the building. The law required the sheriff of the county to maintain his permanent residence in the jailhouse, because there he would be in a better position to guard the prisoners.

Sheriff Jeff McCurtain did not mind living there, because it was rent-free and the rooms were airy in summer and warm in winter. His wife, Corra, though, was a little ashamed of having to live under the same roof with prisoners. Every time she spoke about it, Sheriff Jeff told her that the people on the inside were no different than those on the outside, except that they had been caught. The prisoners in the jailhouse were generally a handful of Negroes who had been caught passing counterfeit dimes and quarters, a few who had shot up a Saturday night church social or fish-fry merely for the fun of it, and every now and then two or three bail-jumpers of both races.

The pounding on the bedroom door stopped for a while, and Sheriff Jeff lay awake listening to hear if whoever it was had gone away. It angered him to be roused up like that out of a sound sleep in the middle of the night. He had gone to a lot of trouble to select reliable deputies who could take care of anything that came up during his sleeping hours. Besides, there was only one prisoner in the jailhouse. He was a Geechee Negro named Sam Brinson, who was being held, as usual, for having sold a mortgaged secondhand automobile. The old car was not worth more than eight or ten dollars, at the most, and Sheriff Jeff was getting ready to turn Sam loose in a few days, anyway.

Corra turned over and began shaking him.

“Jeff, there’s something the matter,” she said, getting up on her knees and working over him as she would over a washboard. Corra was a little woman, weighing less than a hundred pounds. She was a match for him when she could use her tongue, but she knew it was useless and a waste of breath to try to talk to him when he was asleep. Sheriff Jeff was a large man. He was tall and bulky and heavy. He weighed in the neighborhood of three hundred pounds, although in winter he ate more and added fifteen or twenty pounds of seasonal weight. Corra got a good grip on his neck and shoulder and went at him as if he were a pair of mud-stained overalls. “Wake up, Jeff! Wake up this very instant! Something’s wrong, Jeff.”

“What’s wrong?” he asked sleepily. “What time is it in the night?”

“Never mind the time. Wake up like I tell you.”

“A man’s got a right to his sleep no matter what office he holds.”

She shook a little longer for good measure.

“Wake up Jeff,” she said. “Wake up and stir yourself.”

He reached out and turned on the light. He could see his watch on the table under the lamp without having to raise his head. It was a quarter past twelve.

“If that Sam Brinson has broken jail, and one of those deputies came up here and woke me up at this time of night to tell me about it, I’m going to—”

“Shut up, Jeff, and stop that fussing,” Corra said, releasing her grip on his flesh and sitting back on her heels. “This ain’t no time to be quarreling with the deputies or anybody else. Something may be wrong somewhere. Almost anything is liable to happen at this time of night.”

There was another outburst of noise at the door, louder than before. This time it sounded as if somebody had started kicking the door with his foot. Some of the house-flies on the ceiling woke up and came down to the bed.

“Is that you, Bert?” Corra asked in her high-pitched voice. She got up erectly on her knees, clutching the pink silk nightgown over her thin chest. “What’s the matter, Bert?”

“Yes’m,” Bert said. “I hated to wake up Sheriff Jeff, but I thought I’d better.”

Sheriff Jeff slapped at a ticklish housefly that was crawling across his forehead. The exertion made him wider awake. He turned over and sat up on the side of the bed. He moved slowly, his heavy weight making the springs and wooden bedstead creak as if they were going to give way under the strain.

“What’s got into you at this time of night, Bert?” he shouted, fully awake at last. “What’s the sense of making so much noise in the middle of the night like this? Don’t you know I need my sleep? How can I wake up fresh in the morning if my night’s rest is all broken up?” He slapped savagely at another fly. “What’s the matter?”

Corra got up and ran across the room with her little short strides. She took her yellow-flowered wrapper from the hook behind the door and slipped it on.

“What do you want with Mr. McCurtain, Bert?” she said, coming back to the bed, drawing the wrapper tightly around her, and sitting down.

“Tell him I think he’d better get dressed and come downstairs right away, Mrs. McCurtain,” he said uneasily. “It’s important.”

“That’s the trouble with political life,” Sheriff Jeff said, mumbling to himself. “Everything’s important till you look it straight in the face. Once you look at it, it’s pretty apt to turn out to be something that could have waited.”

“Stop your grumbling, Jeff,” Corra said, digging her elbow into his side. “Bert says it’s important.”

“Them smart-aleck deputies, Bert and Jim both, think it’s something important every time a nigger’s caught robbing a hen-roost.”

“You get up and get dressed,” Corra said, jumping to her feet and standing before him with a cross look on her face. “Do you hear me, Jeff?”

He looked up at his wife and slapped at one of the flies tickling the back of his neck.

“Bert!” he shouted. “Why didn’t you wait till daylight? If you’ve got a new prisoner down there, lock him up and I’ll attend to him the first thing in the morning after I’ve had a chance to eat my breakfast.”

He waited for Bert to say something. There was silence outside the door.

“And if one of you smart-alecks has gone and picked up a nigger gal bitch laying-out in an alley and come and woke me up like this to tell me about it, I’m here to tell you I’m going to do something far-fetched. I want them nigger gals left alone, anyway. There’s been too much fooling around with them back there in the cage-room all this summer. I’ll fire both of you deputies quicker than a dog can yelp if you don’t stop it. If you can’t stick to white gals, you’ve got to go somewhere else to do your laying-out with the nigger ones. Tell Jim Couch I said—”

“Jefferson!” Corra said sharply, her voice jabbing him like a pin-prick.

“Well, hot blast it, I want it stopped!” he said roughly.

“It’s nothing like that at all this time, Sheriff Jeff,” Bert said quickly. “You’d better come down right away.”

“Did Sam Brinson break jail after all I’ve done for him?”

“No, sir. The Brinson nigger is still in No. 3. He’s sound asleep back there.”

Corra came and sat down on the bed beside him, drawing the yellow-flowered wrapper tightly around her body as though she would allow nothing of her to touch him. She did not speak right away, but Sheriff Jeff knew by the way in which she looked at him that he was going to have to listen to a lot of talk from her before he left the room. He dropped his head in his hands and waited for it to begin. He could hear Bert going down the stairs.

“Jeff, you haven’t had anything to do with those colored girls yourself, have you?” she finally asked, her voice rising and falling with inflections of tenderness and concern. “I’d die of humiliation, Jeff. I just couldn’t stand it. I don’t know what I’d do.”

When she paused, he shook his head slowly from side to side. From the corners of his eyes he was able to glance at his watch on the table. He had listened to her on the subject so many times in the past that he knew just how long it would take her to say what she had on her mind. He dropped his head wearily back into the confines of his hands and closed his eyes peacefully. It was a relief to his mind to be able to close his eyes at a time like that and think of things far away.

“There was a colored girl locked up from last Saturday night until Monday morning, Jeff. Did you go down to the cage-room while she was there?”

He shook his head.

Corra had started in again when Bert suddenly knocked on the door again.

“Sheriff Jeff, you better come quick!”

“What’s happened, Bert?” Corra asked, jumping up.

“It’s some kind of trouble over near Flowery Branch. A nigger over there got into trouble and a crowd of white men has gone out to look for him. It looks pretty bad, Mrs. McCurtain. Don’t you think Sheriff Jeff ought to get up and come down to see about it?”

Sheriff Jeff groaned miserably. It meant that he would have to get up and dress himself and go fishing. He knew no man alive hated fishing as much as he did.

“Did you hear what Bert said, Jeff?” his wife cried, running to him and shaking him as hard as she could. “Did you hear that?”

He groaned from the depths of his body.

“I’ve grown old long before my time,” he said sadly. “Holding political office is what has caused it. I’m nothing but a frazzle-assed old man now.”

He got up, straining his legs while the weight of his body was becoming balanced, and reached for his clothes. He hated the sight of a fish; he never ate fish; and he would walk several blocks out of his way to escape the smell of one. But going fishing was the only means he had of escaping from a controversial matter. He had had to go away on fishing trips so many times during the eleven years he had been sheriff of Julie County that he knew more about worm- and fly-fishing than any man in that part of the world. He had had to force himself to catch fish in every known manner. He had snared them with a wire-loop; he had seined them; he had shot them with a rifle; and, when he had been unable to catch them any other way, he had dynamited them.

“Jeff,” Corra said, “the best place in the world for you at a time like this is down on Lord’s Creek, fishing.”

He turned on her, his lips spluttering.

“Hot blast it!” he shouted. “Why do you have to say ‘fish’ to me at a time like this when you know how much I hate it!”

“Now, Jeff,” she said placidly. “Just try to control yourself a little.”

“Are you coming, Sheriff Jeff?” Bert inquired meekly from the hall: “That nigger they’re looking for is liable to get caught almost anytime now.”

“Go on down to the office and wait for me, Bert,” he said weakly. “I’ll be down toreckly to see what I can do.”

He got his feet through his pants legs.

“Now, mark my words, Jefferson McCurtain,” Corra began. “If there ever was a time for you to go fishing, this—”

“Hot blast it till God-come-Wednesday!” he shouted, tugging at his pantstops and pulling the waistband over his belly. “Can’t you see the fix I’m in! For eleven years I’ve worked myself frazzle-assed trying to keep from getting mixed up in political disputes just so I can keep this office. And now all you can do at a time like this is to fuss at me. You know this trouble is liable to split the next election wide open. Why do you have to torment me when I’m trying my best to figure what to do?”

“I’m only telling you for your own good, Jeff,” she said tenderly, ignoring his anger.