Too Good to Be True: The Colossal Book of Urban Legends (46 page)

Read Too Good to Be True: The Colossal Book of Urban Legends Online

Authors: Jan Harold Harold Brunvand

No word on which woman got to keep the cat. Just glad he survived his airborne training. Eight lives to go….

This is the full text of a story that I paraphrased in

Curses! Broiled Again!

from the “Bob Levey’s Washington” column in the

Washington Post,

June 1, 1987. I’ve heard several versions of “The Flying Kitten” since then, but none as well told as Levey’s. A reader informed me that the same story appeared in Loyal Jones’s and Billy Edd Wheeler’s 1987 book

Laughter in Appalachia,

and another sent me a press account of a launched cat from Simi Valley, California, in 1991; this feline flier, however, landed safely on a nearby roof and was rescued by its owner.

“The Missionaries and the Cat”

I

’ve heard this from about five different returned Mormon missionaries, all of whom went to different mission locations. This missionary and his companion visited an elderly lady who had a prize cat that was the love of her life and her only companion. But this cat was obnoxious and always sharpening its claws on the missionaries’ legs or getting fur on their dark suits, or whatever.

One day, while the elderly lady was getting the nice young elders some refreshments, one of the LDS elders reached down and flicked kitty on the nose. And as everybody supposedly knows, if you flick a cat on the nose you can kill it by driving its “nose bone” into its brain. This is exactly what happened.

The horrified missionary shoved kitty under the sofa and tried to act as though nothing had happened. On their next visit the missionaries were greeted by a distraught elderly lady mourning the demise of her beloved pet.

Sent to me by Allison Myers of Tucson, Arizona, in 1990. One year earlier I had received the story from Dr. Will Waterhouse, a U.S. Army ophthalmologist then stationed in Landstuhl, West Germany, who had heard it from a friend who had served a Mormon mission in Scotland; in his version the cat had been pawing at illustrations that the missionaries had attached to their low-tech teaching aid, a flannel-covered board. Other versions mention flip charts. Sometimes the cat’s corpse is concealed by the missionaries, but in other versions they simply prop the dead kitty up and keep on petting it until it’s time to leave. In 1991, Sharon Northern of Portland, Oregon, wrote me to ask if I had heard about the old lady in Germany who had slammed her front door in the faces of two Mormon missionaries, breaking the neck of her small dog, which had stuck its head out to see who was on the porch. And in 1993 Jennifer Lewandowski of Elmhurst, Illinois, sent me the story of a piano tuner who rapped a bothersome dog on the head with his tuning fork, accidentally killing the beloved pet. This time the pet’s body was hidden under a bed.

“The Bungled Rescue of the Cat”

THE LEAST SUCCESSFUL ANIMAL RESCUE

The firemen’s strike of 1978 made possible one of the great animal rescue attempts of all time. Valiantly, the British Army had taken over emergency firefighting and on January 14, they were called out by an elderly lady in South London to retrieve her cat which had become trapped up a tree. They arrived with impressive haste and soon discharged their duty. So grateful was the lady that she invited them all in for tea. Driving off later, with fond farewells completed, they ran over the cat and killed it.

Quoted from Stephen Pile’s 1979 book

The Incomplete Book of Failures.

There was, indeed, a British firefighters’ strike in 1978, and this story—which may be true—began circulating the same year. However, different versions are told about both regular firemen and substitutes in the United States as well as in England.

“The Eaten Pets”

D

o Vietnamese residing in San Antonio carry on a well-known culinary practice of their native land—killing and eating dogs?

In the Remount Drive and Dinn Drive area, not far from Windsor Park Mall, strange cooking odors have led to a great deal of conscientious sniffing of late on the part of animal lovers.

“It’s the smell of roasted or boiled puppy dog. Friends of mine living in the neighborhood near all those homes of newly arrived Vietnamese swear to it, and I agree,” says Kathleen Hastings of 358 Savannah Drive, who elaborates:

“Puppies in the same residential blocks are seen for a few weeks, frisking and fattening up in their yards. Then, poof!, they’re gone, never to be seen again, replaced by the aforementioned cooking odors.”

Said Kathleen Walthall of the local Humane Society, “There’s no Texas law against eating dogs so long as they are killed humanely. I wouldn’t do it myself. But if the practice exists here, I have no power to stop it.”

City veterinarian Dr. Annelda Baetz concurred, saying, “Why, the Chow dog was originally bred by the Chinese for purposes of ‘good eating.’ You can’t legally throw dogs to lions or crocodiles in America, but killing them in a humane way in order to prepare a gastronomic delicacy is OK.”

Grumps Kathleen Hastings, “If we don’t have a law protecting defenseless dogs from the jaws of cannibals, we had better pass one—and fast!”

L

ansing—It may be OK for man’s best friend to whimper for scraps under the dinner table, but Fido had better not be the main course.

That’s the message from a state lawmaker who has proposed closing a loophole in Michigan law that allows people to indulge in meals composed of dogs and cats.

The extent of the problem hasn’t been gauged in Michigan, though there are documented cases in other states such as California.

The Michigan Humane Society has received a few complaints from residents in Detroit’s southern suburbs and Lansing who fear their disappearing pets may have ended up on someone’s dinner plate.

“There are some people taking people’s pets off the street and killing them and eating them,” said Eileen Liska, director of research and legislation for Michigan Humane Society.

“They’re not documented cases; we can’t justify undercover surveillance because there isn’t anything in the law that specifically deters it.”

She said officials suspect a few immigrants from southeast Asia, because in their native countries dog is considered a delicacy.

The first example is from Paul Thompson’s column in the

San Antonio Express-News

for April 13, 1988. In a follow-up column published three days later Thompson reported “a whole lot of sniffing…without concrete proof that anyone goes in for ‘roast puppy.’” Four Vietnamese readers who called Thompson insisted that, since meat is plentiful in the United States “no Oriental will be tempted to seek out dogs as a culinary adjunct.” The second example is an Associated Press story of October 8, 1990. Both of these items are typical of many similar articles that have appeared in the American press since Southeast Asian refugees began arriving in large numbers during the 1970s and ’80s. Vague rumors about disappearing pets, strange cooking odors, and supposedly larger problems with pet-eating in another state—usually California—are standard features of such stories. The relationship of the dog breed “Chow” to anyone “chowing down” on dogs is tenuous at best, and the charge that dog eaters are “cannibals,” although ludicrous, illustrates how people regard their pets. Two indisputable facts make the rumors seem credible; first, that pets do sometimes disappear for no apparent reason, and second, that in some Asian countries dogs are sometimes eaten. Efforts to pass laws outlawing the eating of cats and dogs have failed, usually because such legislation could pave the way for laws prohibiting the eating of

any

animals, as advocated by some animal-rights advocates. Stealing of pets and cruelty to animals are already crimes in most places, but there is no proof that either action is involved in whatever rare instances of dog-eating may have occurred in this country. Another eaten-dog story, “The Swiss Charred Poodle” appeared in Chapter 2, and there is a larger genre of stories about unusual meat dishes served in foreign or fast-food restaurants. Another persistent story tells about an immigrant buying a pet pony and, before the eyes of the horrified sellers, killing it to serve at an ethnic feast. I have heard this one over a period of several years in New York, Utah, and (of course) California. The killer is said to have used a two-by-four, a baseball bat, or a gun to kill the pony; the homeland of the killer is said to have been Samoa, Tonga, Vietnam, or “some island,” but, significantly, never France, a country where horse meat is eaten. The prejudices displayed in American “eaten pet” stories are generally directed against Asians, and occasionally against immigrants from southern or eastern Europe.

“The Pet and the Naked Man”

W

e are told, through the news media, to take extra precaution during this cold weather. One advice is to take care of our plants. Sometimes that can be hazardous, as evidenced by this article in the

Batesville (Arkansas) Daily Guard:

Seems the weather turned cold in Houston, Texas, so one man brought an outside hanging plant into the house to keep it from freezing. Said plant contained a small green snake.

The snake warmed up, then slithered onto the floor and under the sofa. The man’s wife screamed. The man, who was taking a shower, ran naked into the front room. He bent down to look for the snake. His dog cold-nosed him in the rear end. The man thought it was the snake, and fainted.

His wife figured it was a heart attack. She called the ambulance. When it showed up the attendants loaded the man on a stretcher. About this time, the snake reappeared scaring the attendants. They dropped the stretcher breaking the man’s leg. And that’s how he landed in the hospital.

From a letter to the editor signed Lydia Sisk, Pasco, Washington, in the

Tri-City Herald,

sent to me in March 1989 by Ellen Schmittroth of Richland. (The third of the tri-cities is Kennewick.) Schmittroth commented that “This smells suspiciously like a myth. It was so funny that I made several copies and sent them all over the place. When I read it to my mother over the phone, she laughed so hard she dislocated her jaw. Maybe the surgeon general should do something about putting warning labels on such stories.” The set-up for this slapstick story is usually a snake that gets into a house, sometimes hidden in the root ball of a living Christmas tree; non-snake versions begin with a clogged sink drain or a broken hot-water heater. The pet involved is either a cold-nosed dog or a curious cat that takes a swipe at the naked man’s testicles. The inevitable conclusion to the story involves startled or laughing paramedics who drop the stretcher and further injure the victim. The above version and Ms. Schmittroth’s note nicely illustrate the channels through which such stories move from person to person and place to place, both in print and by oral tradition.

Back in 1970

columnist Al Allen of the

Sacramento Bee

devoted the very first of his “On the Light Side” columns to telling certain humorous, improbable and oft-repeated stories that he called “Mack Sennetts.” He was referring to the kinds of slapstick scenes found in the old Keystone Kops movies directed and produced by Sennett. These farcical flicks were full of sight gags, chases, sudden reversals of direction, and all manner of loony mishaps and near misses. When I contacted Allen after learning of our mutual interest in such slapstick stories, we agreed that many of the comical urban legends were close relatives of “Mack Sennetts.”

The term “slapstick” actually refers to the sound of two sticks slapping together, or to a sort of paddle, used to create a loud smacking sound that was cued to the climax of silly jokes on the vaudeville stage and in early film comedies. If you got the timing just right, the resounding SMACK! of the slapstick was supposed to give the pie-in-the-face routine or the dropped-drawers gag a bigger comedic punch. In fight scenes, actors might actually slap at each other with a hinged set of sticks so that the force of their feigned blows was underscored by the loud cracking sound. Later the term “slapstick” was applied to the nature of the humorous scene itself, rather than to the background audio. (At least this is what dictionaries say; the whole thing sounds like a theater legend to me.)

At any rate, obvious elements of slapstick comedy are found in some urban legends, especially the stories that involve what I call “hilarious accidents.” Typically in such stories there is a series of mishaps, each worse than the last, all leading up to some kind of exposure of the victim before others’ eyes. The comedy in these legends is simple, visual, physical, and farcical, yet it’s just believable enough to seem convincing when told by a believer to whose friend’s friend the incident happened. Sometimes a punch line destroys the pretense that the slapstick incident really happened, putting the story more into the genre of jokes than legends. Yet the incidents in slapstick legends usually are plausible enough to pass for truth in the minds of some people, especially when the stories get into print.

One of my favorite slapstick legends is about a woman who had to take her son’s pet garter snake to him at school for show-and-tell. She put the snake into what she thought was a secure box, and started out in her car. Before long, however, she felt something tickling her ankle, and when she looked down she saw that the snake had escaped the box and was slithering up the leg of her slacks.

The woman frantically kicked her leg and brushed at it with one hand, trying to dislodge the snake, but it didn’t work, and the snake kept creeping up. So she pulled over to the roadside, jumped out of the car, and began jumping around and even rolling on the ground trying to dislodge the snake.

A man driving by saw her contortions and thought “Oh, my God! That poor woman is having some kind of seizure!” So he stopped his car and ran over to help her. He tackled the woman and tried to hold her still, but she kept screaming and writhing around.

Another man driving by saw this scene and thought, “Oh, my God! That guy’s attacking that poor woman!” So he too stopped his car, ran over, and punched the first man in the face. The woman was finally able to shake out the snake, and then she explained the situation to the two Good Samaritans. This “Snake-Caused Accident” story sometimes involves a gerbil in a box being transported to school or to a vet. Both of these bizarre scenarios may have been invented for use in law school exams, but they have passed on into urban legend tradition.

The concluding story in the preceding chapter, “The Pet and the Naked Man,” is another good example of a slapstick urban legend. The sequence of mishaps there goes snake-in-house/naked-man’s rescue/accident caused by curious pet/second accident caused by laughing paramedics. Few people hearing the story really stop to question

why

the man would try to find the snake while still naked from the shower or how likely it would be for the snake to reappear just as the paramedics are loading the stretcher. But if you start to question the elements of a farce too closely, it isn’t funny anymore.

The “laughing paramedics” element of the story almost deserves to be classified as a separate legend, except that it always appears attached to an account of another mishap. In this chapter, for example, laughing paramedics enter the scene following an exploding toilet or another hilarious accident involving a man on a roof. When you think about it—except that nobody

does

think about these things—paramedics nowadays use wheeled gurneys, not hand-carried stretchers, and they surely must be trained to maintain a dignified professional reserve and to hang on to the patient, no matter how ludicrous the accident they are attending. But the “laughing paramedics” is a slapstick scene inserted into several comical legends.

Another nice thing about these laughing paramedics is that they clue listeners in to how they are expected to react. So if you’re trying to get full effect from a funny story you’re telling, just throw in an accident, followed by some paramedics who are laughing their heads off.

“Lost Denture Claim”

A clerk in an insurance company was processing a claim for a lost pair of dentures. He requested more information on how they were lost.

The policyholder explained that it all started when she ran out of toilet paper. She came home from buying some at the store and realized that now she had to answer a call of nature rather urgently. So she headed quickly for the bathroom while tearing open the package of toilet paper.

In her haste, as she entered the bathroom, she tripped and dropped the package of toilet paper. She lunged for the dropped package and simultaneously reached out with her arms to break her fall; her left hand hit the handle of the toilet just as her chin hit the edge of the bowl. Her dentures were jolted into the toilet bowl, and the swirling water flushed them down the drain.

“The Exploding Toilet”

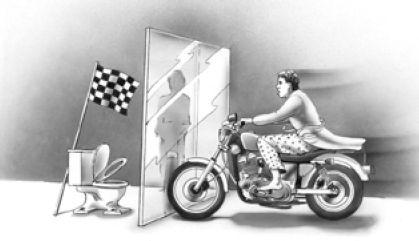

GREAT MOTORCYCLING RUMORS

We have heard this story told and seen it printed half a dozen times in the last 30 years. It is always related as fact. Most recently, one of our editors heard it from a paramedic who was teaching a seminar on emergency medical care.

Robert Enriquez

The story begins with a new owner cleaning his bike on the patio outside a plate glass door or window. When he finishes cleaning, he starts the bike. Somehow he manages to lose control, sending him and the bike through the plate glass window. In the process, he suffers multiple lacerations and paramedics are called. He is summarily rushed to the hospital for stitches. His wife is left to deal with the fallen bike, which is now dripping gasoline on the living room rug. Unable to lift the motorcycle, she uses toilet paper to soak up the gas. When the TP is saturated, she replaces it with more and puts the gas-soaked paper in the commode.

Finally, her husband returns home sporting stitches and bandages. He rights the bike, returns it to the patio and retires to the bathroom, where he seats himself on the commode and, inevitably, lights a cigarette. He drops the match into the commode, which is full of gasoline-soaked paper and fumes. The commode explodes, launching him through the glass shower door. The paramedics are called again, but they are laughing so hard as they try to remove him to the ambulance that they drop the stretcher.

The bike is sold the next day.

This is from

Motorcyclist

magazine, September 1991. The same magazine also had published the story in February 1984. My colleague at the University of Utah Adrian “Buzz” Palmer spotted both stories. In a variation on the theme, the man is trying out a new mini-bike he has bought for his children when he spills the gasoline. In a version from New Zealand the man is working on his “leaky car petrol tank” and drains the tank into a toddler’s potty, which his wife then pours into the toilet. Whatever the set-up, these variations invariably describe broken glass, spilled gasoline, the wife’s involvement in the accident, and (of course) laughing paramedics. There are also many nonvehicular versions of “The Exploding Toilet” in which the volatile material put into the toilet is hair spray or insecticide. Yet other versions begin with a different accident that sends the husband to the hospital; in his absence, the wife paints the bathroom and pours paint thinner into the toilet, leading to the second mishap. In 1988 a version of “The Exploding Toilet” was reported as news from Tel Aviv and rapidly spread worldwide in the media until it was retracted by the newspaper in Israel that had first reported it. An analysis of this incident, plus a history of exploding-toilet stories back to the days of outhouses, is included in my book

The Truth Never Stands in the Way of a Good Story,

in the chapter “A Blast Heard ‘round the World.” The punch line in the rural prototype of the legend was, “It must have been something I et!”

“Stuck on the Toilet”

T

his story was told to me many years ago by a friend of mine who said his father, a physician, was present at the hospital in California where it happened.

A young doctor had the day off and a pair of tickets to a concert. He puttered around the house, did some chores, then picked up a baby-sitter and took his wife out for the evening.

During the intermission they called home to check on things. There being no answer, they hurried back. Dashing into the house, they called the baby-sitter’s name and heard her respond from the bathroom. There they found her stuck tight to the toilet seat, which the doctor had re-varnished that morning.

Unable to free her, they unbolted the seat, covered the girl with a blanket, and took her to the hospital emergency room. But even the specialists there were unable to detach the seat from the sitter. When all else failed, they put the poor girl on her hands and knees on an examination table and began to use a scalpel to slice away the varnish just a micron away from her skin.

As word of this strange predicament spread among the hospital staff, the emergency room attracted a crowd of doctors and interns. At this point, the chief of staff, who was making his rounds, walked in. An intern standing next to him, trying to act nonchalant, asked the chief, “Have you ever seen anything like that?”

The chief replied, “Yes, many times. But never with a frame around it.”

Sent to me in 1989 by Cliff Thompson of Gahanna, Ohio. The punch line here—a feature more typical of a joke than a legend—is a sure sign of the farcical nature of this story. In other versions, injuries are multiplied when the doctor sits on the edge of the bathtub while trying to free the girl, slips, and either breaks a limb or suffers a concussion. Sometimes his accident is caused by his uncontrollable laughter, and occasionally, laughing paramedics enter the scene. Another contemporary stuck-on-the-toilet story describes a very fat passenger who becomes stuck fast onto the plastic seat of a toilet on a cruise ship or an airliner; there is some evidence that such accidents have actually occurred, although most retellings are strongly influenced by the stuck-toilet urban legends. These modern legends, in turn, may derive from older folk stories that described people becoming stuck to chamber pots.

“The Man on the Roof”

A

32-year-old roofer was jerked to the ground and dragged almost 200 feet when his wife drove away in the family car with his safety rope tied to the bumper!

David Willis was hospitalized with a broken leg, cracked ribs, concussion and numerous bumps and bruises after the bizarre accident.

But he told reporters in Cape Town, South Africa, that he’s lucky to be around to talk about his close call.

“One second I was hammering the roof and the next I was plowing up tomato plants in the garden,” he continued.

“Everything happened so fast it was like a dream. But I was in so much pain I knew that what was happening was real.”

Willis said the drama unfolded a few minutes after he climbed onto the roof of his house to replace some weather-beaten shingles.

He tied one end of a safety rope to the chimney and pulled the loose end through the belt loop in his pants. He then dropped the rope down to his 9-year-old son and told him to attach it “to something secure.”

The dutiful child promptly tied the rope to the bumper of his mother’s car and scampered off to a nearby park to play.

“My wife and I spoke to each other as she got into the car to go shopping,” said Willis.