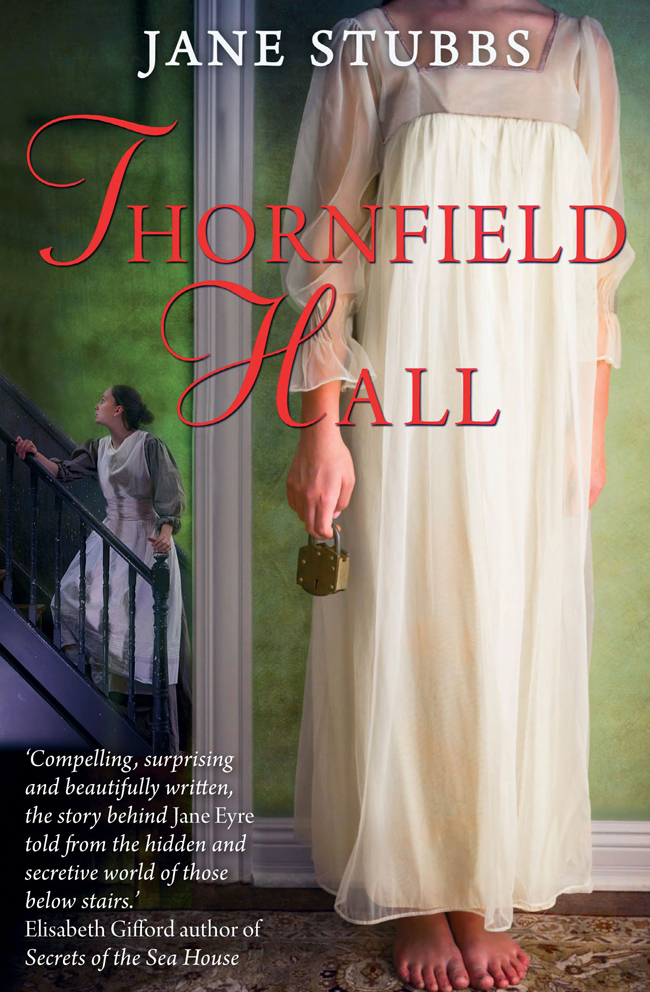

Thornfield Hall

Authors: Jane Stubbs

Jane Stubbs

studied English at London University. She went on to teach the subject to a variety of ages in colleges and schools. As well as raising a family, she has worked for various charities, has written a weekly column for a Scottish newspaper, and has won prizes for her short stories.

Published in paperback in Great Britain in 2014 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Jane Stubbs, 2014

The moral right of Jane Stubbs to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author's imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 782 39524 9

E-book ISBN: 978 1 7823 9523 2

Printed in Great Britain.

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26â27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

To Alan who understood

CONTENTS

The Incident in the Library: 1826

The Honourable Blanche Ingram: 1827

A Year of Tumultuous Events: 1832

Martha and I Join the Gentry: 1832

Other Characters from the Classics that Could Have their Story Told

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks are due to many people. Here are some of them:

First and foremost to Charlotte Brontë for writing a novel so full of vivid life that it is possible to walk about her creation and look behind the scenes.

To Teresa Chris for finding a publisher.

To Atlantic for bringing my infant to full term.

To the late Maggie Batteson, Pat Hadler, Mary Sharratt and Cath Staincliffe for their patient reading and helpful comments on my apprentice pieces.

Last but not least to A G de C Smale, she of the elegant initials who first introduced me to the glories of the English language and to all the others who followed in her footsteps.

MY FIRST MR ROCHESTER

1821

I

T WAS AFTER I'D GONE TO MY FIRST MR ROCHESTER

that my hair turned white. They do say it can happen overnight through disease or grief. In my case it was not so dramatic. Day by day the gold in my hair gently faded away until it was a pure snowy white. There I was, not yet forty and I had the hair of an old woman. I cannot blame illness for my transformation but I do think grief played its part. There had been many bereavements in my life, and in going to Thornfield Hall as housekeeper I said farewell to something that I had been raised from a child to regard as precious beyond rubies. According to my mother its preservation was as vital to an unmarried girl as her virginity. Like a maidenhead it was something to be treasured, not disposed of carelessly in an idle moment, for once lost it could never be recovered. I refer not to my virginity, which is long gone, but to my place in society. By being employed as a paid servant I was cast out from that privileged class of beings â the gentry.

My mother was gentry. As the daughter of a gentleman and the widow of a clergyman she claimed it as her birthright. She

clung desperately to this status. It seemed to console her for the poverty and the meagreness of her life. Throughout my rather miserable childhood she drummed into me the importance of this mystical privilege that a gentlewoman must at all costs cherish and preserve. Never mind that we dined on crusts and scraps and had no fire before six o'clock of an evening; we were gentry and we had a servant to prove it, some poor unfortunate twelve-year-old village girl cozened into washing our dishes for a few pennies a week. If my mother ever discovered that I had swapped genteel poverty and semi-starvation for the good food and warmth enjoyed by the servants of a wealthy man she would turn in her grave.

For that is where she is. She left this world early but not before she contrived to see me suitably settled in life. Marriage was the only path open to me; my mother's constant lectures made that clear. I sleep-walked to my wedding. I woke one day to find I was married to the parson of the church in the village of Hay. Now a parson, no matter how poor he is, always counts as gentry. He will be invited to the big house for lunch during the week or supper on a Sunday. He will go to the front door and a servant will take his hat. The parson's wife, therefore, counts as gentry. And so my mother died happy that she had done right by me.

I was not with my parson for long. Just time enough to have and to lose one beautiful baby girl. Then the coughing sickness took my parson the next winter and by spring the new incumbent was knocking on the door of the parsonage. Mr Wood, the replacement for my husband, had a pack of children and he was anxious to introduce them to their new home and to see the back of me. I was at a loss as to what to do.

My late husband was a sweet-tempered and mild-mannered man. He was very much a follower of the New Testament; he

trusted in the Lord to provide. Consider the lilies of the field. Lay not treasures up for yourself on earth. That sort of thing. I am more of an Old Testament person myself. I like the drama of it: the feuds, the plots and the adultery. Perhaps that's why the Lord did not see fit to provide for me when I became a widow.

With no home and no income I became that most uncomfortable thing, a distant relative in need. My late husband was a Fairfax so I applied to his family. They sighed and held up their hands to show they were empty. They shuffled me about from house to house whenever there was extra work to be done. I sat up nights with the dying. I nursed the sick. While the family went away to the seaside I stayed to supervise the spring cleaning. They derived much satisfaction from being such exemplary Christians as to feed me and give me a roof over my head. They conveniently forgot that unlike a servant I received no wages.

It was an interesting if precarious life. A second cousin summoned me to help when her third baby was due. Her two lovely boys were soon joined by a baby girl. Such a pleasant time I had. I grew very fond of the children and began to hope I might make a real home with the family. One morning I was in the nursery supervising the children at their breakfast. The baby wriggled on my knee as I spooned porridge into her. Their mother arrived in her dressing gown with a letter in her hand. She waved it at me as she gave me the news. The wife of old Mr Rochester of Thornfield Hall had died; she too had been a Fairfax. To my second cousin the news was not all bad; she saw an opportunity to move me on.

âI'm sure Mr Rochester would be grateful for some help at this sad time, Alice. Especially from a female relation. Someone he could trust to deal with all those things his wife always dealt with. Men know nothing about running a house. You know what

I mean: keep the housemaids in order, tell cook the soup was salty. I'll be sorry to see you go,' she said, âbut I won't need so much help soon. The boys will be away to school in the autumn.'

I could see her mind working. She was thinking, Thornfield Hall is a large house. There must be a room somewhere that a parson's widow could occupy. She could do a little light needlework. She does not eat much. A bit of a fire in the winter. Old Mr Rochester is a man of property and wealth; he would not let a connection of his wife's starve. He would lend her back to me if, God forbid, I have another baby.

I was angry. And I was jealous. She had everything I had been denied. She had a husband with an income while I was a penniless widow. She had three healthy children while I had lain to rest my one baby girl who had scarcely drawn a breath. The rage churned about in my bosom all day. I hammered it down while I smiled and played with the boys and stroked the baby's soft hair. I knew I would be saying farewell to them soon.

My late husband always said his prayers before he lay down to sleep. In the morning he frequently claimed that his prayers had been answered. That night I berated God. I gave it to him hot and strong, told him that he had been unreasonably harsh in his dealings with me. I put it to him fair and square. I do not think my long and bitter diatribe could be regarded as a proper prayer but to my surprise I awoke with my mind clear and with a settled plan for determined action. You could say that my prayers had been answered.

I wrote to old Mr Rochester, with whom I was already acquainted. I reminded him that not only was I a Fairfax, I was also the widow of the parson at Hay whose church was close to the gates of Thornfield Hall. I included a suggestion that would have shocked my second cousin if I had been so foolish as to reveal it to her. I received an encouraging response. Some

haggling followed but in the end I struck a bargain with the senior Mr Rochester that suited both of us. I knew how to run a house with economy and he could trust me not to steal the spoons. I became the paid housekeeper at Thornfield Hall.

Suddenly I wasn't gentry anymore. I was a servant, an upper servant to be sure, but a servant nonetheless. My second cousin went through a range of emotions. She was shocked that I had chosen to lose caste, angry that she could no longer call upon my unpaid services and finally relieved that the Fairfaxes could with clear consciences wash their hands of me. This they did with alacrity. I was on my own. It was frightening but also exhilarating. I squashed the flutterings of doubt that beat in my breast and set off to take up my new duties.

Mr Merryman, the butler, greeted me on my arrival at Thornfield Hall. I never saw anyone so unsuited to his name; his lugubrious face with its hanging jowls reminded me of the dogs they use for hunting hares and rabbits. Mr Merryman took it upon himself to ensure that I learnt how to do things properly. He would dine with me in the housekeeper's room. Our meals would be brought on a tray by one of the lower servants.

âWe,' he informed me, âare senior servants. Sometimes we are known as “pugs” because we wear a serious expression with our mouths turned down like the pug dogs.' He gestured to his own face with its drooping mouth. âSometimes,' he sighed, âI think it's permanent; I've done it for so long.' As he showed me round the house Mr Merryman explained various other matters that he thought it important for me to know about my new position. As a mark of respect I would be called Mrs Fairfax by both the staff and the family, rather than just âFairfax' as if I were a chambermaid.