This Great Struggle (51 page)

Read This Great Struggle Online

Authors: Steven Woodworth

Alabama

was in harbor at Cherbourg, France, where her captain, Raphael Semmes, had tried and failed to get the French authorities to ignore their nation’s neutrality and allow him the use of their dockyards to overhaul his vessel, when on June 14, 1864, the USS

Kearsarge

arrived and stood off the harbor entrance, obviously awaiting the

Alabama

. Five days later Semmes took his vessel to sea, and the two fairly evenly matched men-of-war fought the most spectacular ship-to-ship battle of the conflict, watched by thousands on the French shore. In a little more than an hour, the

Kearsarge

sent the

Alabama

to the bottom, ridding the seas of the greatest nuisance and threat to Union trade.

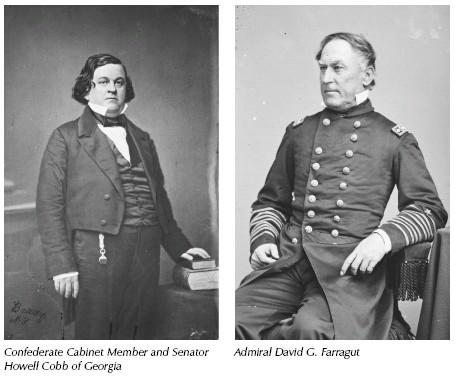

A little less than seven weeks later the U.S. Navy had scored another success, this time in American waters. On August 5 the old sea dog Farragut, in his wooden flagship

Hartford

, had boldly led his squadron of ironclads and wooden ships into Mobile Bay past two powerful Confederate forts. One of his most powerful ironclads, the monitor USS

Tecumseh

, struck a mine (then called a torpedo) and went down, but the rest of Farragut’s ships got through. Inside the harbor they met the CSS

Tennessee

, the most powerful ironclad the Confederacy ever built, and pounded it until it surrendered. With that, the Confederacy’s only remaining major Gulf Coast port was closed beyond hope of further use by blockade-runners. Union presence in the bay posed a constant threat of further offensive action against the city of Mobile itself.

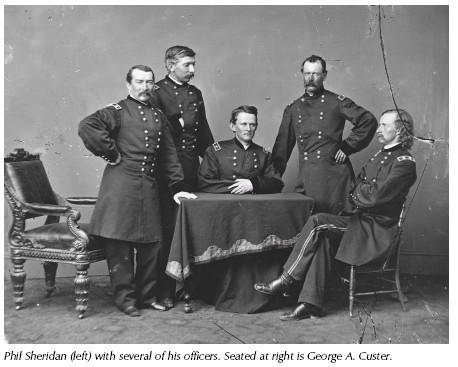

Additional Union successes followed close in the wake of Sherman’s capture of Atlanta. After Early’s raid on Washington, the Confederate had withdrawn into the lower (northerly) Shenandoah Valley and there had remained as a continuing nuisance to Union operations in Virginia, with an ongoing threat to make another lunge toward Washington or Baltimore. Dissatisfied with the apparent inability of the Union generals in that area to see Early off for good and all, Grant assigned Sheridan to take two divisions of his cavalry and take command of all of the Union forces operating against Early and unite them into a hard-hitting Army of the Shenandoah that would neutralize both Early and the valley whose name it bore. Sheridan’s new army would include the Federals previously operating in West Virginia under Major General George Crook as well as the Sixth Corps and the Nineteenth Corps, the latter recently transferred to Virginia from the Department of the Gulf, where it had soldiered grimly through Banks’s dismal Red River Campaign.

Sheridan took over his new army in early August and took several weeks preparing his force and feeling for Confederate weak points. Though badly outnumbered, Early seemed to believe he had little to fear from Sheridan. He found out otherwise when on September 19 the new Union commander attacked the Confederates near Winchester. In the war’s third battle to take its name from that town, the opposing forces slugged it out in a daylong fight. Then as the Rebels began to fall back under heavy Union attacks, the Union cavalry came thundering down on the Confederate flank, turning the retreat into a rout. Early’s army survived though badly battered and suffering the loss of experienced officers such as Major General Robert E. Rodes, one of the Army of Northern Virginia’s most aggressive division commanders, who was killed in the fighting.

Early fell back twenty miles to the vicinity of Strasburg, where he took up a strong position with his right flank anchored on the North Fork of the Shenandoah and his left on Fisher’s Hill. Sheridan followed aggressively and again engaged the Confederates on September 21. After heavy skirmishing that day and the next morning, Sheridan, at Crook’s suggestion, launched a flank attack that crumbled the Confederate line. Defeated again—and more soundly than before—Early retreated all the way up the valley, another eighty miles to the vicinity of Waynesboro. This left virtually the whole length of the Shenandoah Valley open for Sheridan to begin to implement the second part of the instructions Grant had given him when assigning him there.

For three years the Shenandoah Valley had been the granary of Virginia, and its thriving farms had provided food for Confederate armies passing through it on their way to gaining positions of leverage over the Union forces operating east of the Blue Ridge. In the spring of 1862 it had been Jackson’s small army throwing a scare into Washington by its sudden move down the valley. That fall Lee had planned to draw supplies through the valley to support his invasion of Maryland. In the summer of 1863, the valley once again provided food for Lee’s army as it marched through on its way to invade Pennsylvania. A year later, Early had made use of the valley in the same way for the raid that took him to the outskirts of Washington and forced the diversion of the Sixth Corps from Grant’s operations around Petersburg. In each case the agricultural abundance of the Shenandoah Valley had enabled Confederate commanders to operate without the constraints of logistics—the laborious task of supplying an army in the field—that would otherwise have slowed their movements and limited their reach. Thus, in the strange ways of war, it was the idyllic farms and rich harvests of the Shenandoah Valley that had made possible things like the appearance of Early’s army on the doorstep of Washington and the burning of Chambersburg.

Now Grant was determined to put a stop to that, at least until the next year’s harvest came in. “Eat out Virginia clean and clear,” he had ordered Sheridan, “so that crows flying over it for the balance of the season will have to carry their own provender.” With Early having abandoned the lower hundred miles of the valley, Sheridan was now free to carry out that order, and he did his best. He later reported that during the first two weeks of October his troops slaughtered thousands of cattle, sheep, and hogs and burned “2,000 barns filled with wheat, hay, and farming implements” as well as “over seventy mills filled with flour and wheat.”

It sounded like a great deal, and if one happened to own one of the targeted barns or mills, it was a severe loss. Yet it was far short of a total devastation of such an abundant farming district. For the most part, the Yankees did not burn houses. Furthermore, letters and diaries reveal that for most inhabitants of the valley, life went on in its accustomed way, with the usual round of dances and other celebrations, and farmers were taking wagon loads of grain to market only weeks after the passage of Sheridan’s army. No evidence exists that anyone starved, either in the Shenandoah Valley or anywhere else in the South, outside of prison pens such as Andersonville. Like other instances in which Union forces struck at Confederate logistics during the final year of the war, “the Burning” of the Shenandoah, as it came to be called, grew larger in legend than in life, as passing generations exaggerated its destructiveness with each retelling.

Throughout Sheridan’s operations in the valley, as in other Union campaigns in the South, valley residents, though often frightened at the approach of the enemy, were in fact quite safe in their persons, as the killing or injuring of noncombatants was all but unheard of. Rapes were as rare as elsewhere in the presence of the armies of either side, a rate that compared favorably to that of most major cities. Indeed, as nineteenth-century mores dictated, women enjoyed immunity even when they demonstrated hostility to Union troops. Such hostility was most often verbal, but even when a woman swung a broom at a foraging bluecoat, the result was usually that the assailed soldier ducked and his buddies laughed.

When civilians became combatants, however, the situation was quite different. Men who implicitly claimed immunity as civilians when large numbers of Union troops were present but then bushwhacked isolated soldiers forfeited not only that immunity but also any right to be treated as prisoners of war. If captured, they could, under the laws of war, face summary execution. Their actions also exposed the surrounding neighborhood to greater destruction of property. When on October 3 Sheridan learned that his engineer officer, Lieutenant John R. Meigs, had been murdered by bushwhackers near the village of Dayton, he ordered the burning of every house within a five-mile radius but relented and canceled the order after his troopers had torched only about thirty houses and barns. Confederate guerrilla leader John S. Mosby and his troopers continued to be a constant thorn in Sheridan’s side.

While Sheridan’s men strove to destroy the valley’s usefulness for future Confederate offensive operations, Early planned a comeback. He marched his army, somewhat recovered from its previous drubbings, down the valley until he neared the town of Strasburg. Sheridan’s army was encamped just north of Strasburg, along Cedar Creek, a tributary of the North Branch of the Shenandoah River. In a well-conceived plan for a surprise flanking attack, Early marched his troops through the night of October 18 and struck the Union left out of the dawn mists the next morning. Crook’s contingent folded quickly under the surprising onslaught, and the Nineteenth Corps, in the center, gave way after a somewhat harder fight. On the Union right, however, the Sixth Corps was able to rally and hold its ground. Early was delighted nonetheless as the fugitives of the two routed Union corps streamed down the valley toward Winchester in retreat. He was confident that the Sixth Corps would soon follow its comrades to the rear without his having to hurl his thinned gray ranks against it in potentially costly attacks.

Sheridan had not been present for the early morning fight. He had traveled to Washington to confer about future operations and had been on his way back to the army. He was in Winchester that morning, twelve miles from the battlefield, when the sound of the guns reached him. Mounting his large black stallion Rienzi, Sheridan galloped southward along the Valley Pike toward Cedar Creek. He began to meet stragglers heading the other way. The men recognized the small general on the big horse and cheered wildly, but Sheridan roared for them to turn around and march back toward the enemy. And they did.

Arriving on the battlefield around 10:30 a.m., Sheridan found the Sixth Corps steady and Early apparently not inclined to press his advantage. Sheridan spent the middle hours of the day getting his army back in order and then at 4:00 p.m. launched an assault that crushed Early’s army, recapturing the eighteen guns the Union had lost in the first phase of the battle and taking twenty-five more that had belonged to the Confederates that morning. For the Confederate infantry, what had started as a battle ended as a footrace to escape the pursuing Federals. Early retreated far up the valley with what was left of his command, but it would never again pose a threat to Sheridan or anyone else, and the Confederacy would never again make use of the Shenandoah Valley.

THE ELECTION OF 1864

The Union victories in the English Channel and at Mobile Bay, Winchester, Fisher’s Hill, Cedar Creek, and, above all, the capture of Atlanta cut the ground out from under the Democrats’ claim that the war was a failure and could never be won. On the contrary, Union forces were striding toward victory with seven-league boots, and the Confederacy’s days were clearly numbered. This had been true for some time, but the fall of Atlanta focused the public’s attention and brought the progress of the war into perspective so that its trend became unmistakable even for civilians who understood little of military affairs.