This Great Struggle (46 page)

Read This Great Struggle Online

Authors: Steven Woodworth

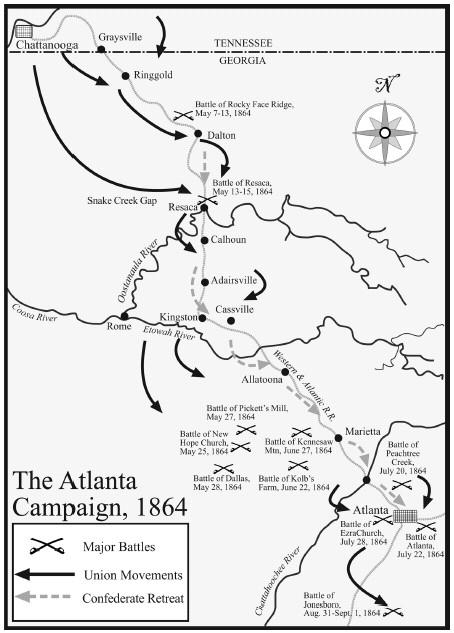

Sherman had won all of his Civil War success thus far in the Army of the Tennessee, and he had taken over command of that army when Grant had moved up to command of all of the western armies the previous autumn. Now that Sherman in turn had taken over command of the all the western armies, he still had great confidence in his old outfit, which he knew would march fast, strike hard, and overcome most natural obstacles. Sherman planned for the Army of the Tennessee to debouch from the gap and tear up the Western & Atlantic well behind Johnston’s army, then pull back slightly and assume a strong defensive position. With his supply line broken, Johnston would have to retreat. As he did so the Army of the Tennessee would fall on his flank, and the rest of Sherman’s forces would crash down from the north to complete the destruction of Johnston’s army.

Commanding the Army of the Tennessee now was thirty-six-year-old Major General James B. McPherson. An Ohioan like Grant and Sherman, McPherson had risen from childhood poverty to graduate first in the West Point class of 1853, and in the Civil War he had risen rapidly in rank. Suave, polished, handsome, and genial, as well as genuinely concerned for the welfare of his men, the young general was as popular with his troops as he was well liked by his superiors. McPherson seemed nearly perfect in every way, and if he had any fault as a general it may have been that his perfectionism did not allow him to feel comfortable in situations that were not completely within his control.

On May 9, as five hundred miles to the northeast Grant’s and Lee’s armies were taking up their positions outside the Virginia hamlet of Spotsylvania Court House, McPherson, in his first independent operation as an army commander, led the Army of the Tennessee through Snake Creek Gap undetected by Johnston and with all the speed and resourcefulness Sherman had expected. He emerged from the gap and was approaching Johnston’s vital Western & Atlantic supply line before he encountered the enemy and then only light forces guarding the Confederate rear. His lead elements were within half a mile of the tracks and driving the enemy easily when McPherson became worried and ordered his troops to fall back, leaving the railroad intact. Brilliant as he was, McPherson had assumed his enemy was equally perspicacious and therefore reasoned that Johnston must be about to descend on him with most of the Confederate Army of Tennessee. McPherson kept his Army of the Tennessee entrenched in a strong position in the mouth of Snake Creek Gap for the next two days, while Johnston finally learned of his dilemma and hurried troops south to confront McPherson and protect the Confederate line of communication and retreat.

Sherman was deeply disappointed at the failure to cut Johnston’s communications and gently chided McPherson that he had lost the opportunity of a lifetime. Nonetheless, adjusting to the partial failure of his plan, Sherman took his other two armies around via the route McPherson had taken so as to come up behind the Army of the Tennessee at the mouth of Snake Creek Gap and support it in a much more powerful move to cut the Western & Atlantic.

Meanwhile, because of Banks’s failure in the Red River Campaign and consequent failure even to launch the campaign Grant had ordered against Mobile, Confederate Lieutenant General Leonidas Polk was free to bring nineteen thousand Confederate reinforcements up from central Alabama, arriving in Resaca just in time to secure the town and with it the Oostanaula River bridge. Johnston made good his escape from Rocky Face Ridge and fell back twenty miles to confront Sherman with more than sixty thousand men in extensive entrenchments anchored on the Oostanaula below Resaca and stretching in a long arc across the western and northern sides of the town. Heavy skirmishing, sometimes escalating to battle intensity, occupied the next two days as Johnston hoped once again that Sherman would send his troops to their deaths in hopeless frontal assaults, and Sherman again declined to oblige him.

Instead, Sherman had a brigade of the Army of the Tennessee stage a cross-river assault upstream from the Confederate entrenchments on the north bank. There Johnston had posted fewer defenders. Even at that the river crossing was difficult, with teams of soldiers lugging heavy boats down to the bank under fire and then rowing across the Oostanaula to storm the Confederate lines. The rest of the Army of the Tennessee quickly followed, and Johnston was turned again. Rather than risk being trapped on the north bank by Sherman’s Federals seizing the crossing from the south side, the Confederate general once again put his army in retreat. His troops crossed the Oostanaula during the predawn hours of May 16 and burned the railroad bridge behind them. Sherman’s expert and well-equipped railroad repair crews got to work immediately and soon had supply trains rolling into Resaca and ready to proceed southward in the wake of Sherman’s now rapidly advancing armies.

Johnston’s army marched steadily southward, as the Confederate general looked for a defensive position he liked. Sherman followed with his three armies spread out on three different roads, five to ten miles apart. The great host could march more rapidly that way, and the formation offered Sherman the chance of bringing one of the side columns crashing down on Johnston’s flank if the Confederates were to turn and “show fight,” as the Civil War soldiers put it.

In fact, under Richmond’s nearly constant prodding to turn and fight, Johnston decided to do just that. He believed he saw an opportunity of catching the Army of the Ohio, smallest of Sherman’s armies, isolated on the Union left near the town of Cassville. He positioned Hardee’s corps to screen off Sherman’s other two armies and massed Hood’s and Polk’s corps to fall on Schofield’s single-corps army. With preparations complete, Johnston issued a grandiose proclamation to his troops, to be read aloud to every regiment in the Army of Tennessee, expressing confidence that God was supporting the Confederate cause and the intention of leading the army in an offensive that would crush its enemies.

Then events took an unexpected turn. Sherman’s armies possessed the intangible advantage of momentum. A brigade of Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland had missed its road some miles to the north and had veered out of the column and far out to the Union left, behind the route of Schofield’s Army of the Ohio. On realizing his mistake, the commanding officer of the errant brigade had decided not to backtrack but rather to keep his men tramping south and seek roads that would angle back to the southwest and reunite him with the main column.

As Hood’s corps, on the Confederate right, waited to spring the ambush on the unsuspecting Schofield, Thomas’s wandering brigade bumped into the rear of Hood’s right flank. Hood had a reputation for all-out aggressiveness, and it was that reputation that had won him his present assignment, as Davis had hoped the young Texan’s relentless combativeness would counterbalance Johnston’s excessive caution and propensity for retreat. But Hood had won his reputation in old Virginia, and the Yankees back there had seemed to belong to a different breed, not the kind that suddenly appeared on one’s flanks and rear just when one was expecting to flank them. Hastily Hood redeployed to defend his flank and sent word to Johnston that, threatened as he was, he now could not take part in any attack. Shocked, Johnston called off the offensive.

Meanwhile, the commander of the off-course Union brigade, taking stock of the mass of Confederate troops his advanced units had spotted ahead, decided that perhaps a little backtracking might be in order after all. Thus, Confederate reconnaissance turned up nothing on Hood’s flank, but by that time the day was well spent, and Sherman’s separate columns were converging in front of the Confederate position. Johnston met with his corps commanders to try to sort out the situation. Hardee urged that they once again stand their ground and dare Sherman to assault their position, but Hood and Polk claimed that their positions were indefensible, enfiladed by Union artillery, and that the best course of action was to attack the enemy the next day, though by now the temporary local advantage in numbers that had initially lured Johnston to attack was long gone. Johnston weighed his generals’ advice and decided to split the difference and retreat.

On May 20 the Army of Tennessee once again turned its back to the enemy and marched southward, this time crossing the Etowah, while some of the Confederate soldiers wept openly in their disappointment and the abandoned citizens of towns like Cassville and Kingston fled in confusion or waited in mute astonishment for whatever a Yankee occupation might bring. Already Johnston’s retreats had uncovered not only the towns along the Western & Atlantic but also those that lay downstream along the southwestward-slanting rivers in the Confederacy’s infant military-industrial complex in northwestern Georgia and northern Alabama. Union troops had recently taken possession of Rome, Georgia, with its vital iron mills and cannon foundries.

FROM THE ETOWAH TO THE CHATTAHOOCHEE

Two of the three river barriers were now behind Sherman, but the highest and steepest of the ridges lay just ahead, and Johnston was heading for the narrow defile where the railroad crossed the highest of them, Allatoona Pass, determined to establish the most formidable defensive line he had yet placed in Sherman’s path. Once again Sherman’s knowledge of the North Georgia terrain stood him in good stead. Aware that Allatoona Pass would be impregnable, he chose not to approach it at all but rather to undertake his boldest turning movement thus far in the campaign. Loading the supply wagons with as much hardtack as they could carry, he cut loose from the Western & Atlantic and struck out due south while the tracks angled off to the southeast toward Allatoona and the eagerly waiting Johnston. Sherman hoped to swing wide around Johnston’s left (western) flank and, if Johnston did not react promptly, reach the Chattahoochee in less than a week, trapping the Confederate Army of Tennessee.

Johnston, however, was alert this time and quickly swung his own army west to meet Sherman. On May 26, the same day that up in Virginia Grant decided there was little more to be gained on the North Anna lines and launched the turning movement that would take the Army of the Potomac to Cold Harbor, Sherman’s and Johnston’s armies made contact south of Pumpkin Vine Creek, along a line stretching from Dallas, Georgia, on the west through New Hope Church to Pickett’s Mill on the east. On that day and the next, Sherman launched corps-sized probes at the latter two places, finding the Confederates entrenched and suffering more than a thousand casualties in each of the two encounters. Johnston surmised that Sherman’s vigorous testing of the eastern end of his defenses might mean that Sherman’s own lines were thin at their western end and ordered William B. Bate’s division to test the hypothesis on May 28. Bate’s men suffered a repulse that differed only in scale from the rebuffs Sherman’s men had received at New Hope Church and Pickett’s Mill.

Days of heavy skirmishing followed, with neither side gaining much of an advantage and conditions made still more miserable by steady rain. With rations running low, Sherman needed to get back to the railroad, so he tried another turning movement, this time lunging east and passing Johnston’s right flank. Again Johnston was quick to react and June 9 was in position again astride the Western & Atlantic, blocking Sherman’s road to Atlanta. Yet despite Johnston’s success in blocking Sherman’s sidelong moves, each one had brought him a little closer to his goal. The net effect of his zigzag from the Etowah River bridge west to Dallas and then back east to the railroad had been to move the Union forces fifteen miles closer to Atlanta and, most significantly, past the impregnable defensive position at Allatoona Pass.

By now Sherman’s armies had reached Big Shanty (the present-day town of Kennesaw) ninety miles from their starting point at Chattanooga and only twenty-five from Atlanta. Ahead of them, however, lay another ten miles or so of terrain only marginally less forbidding than the range they had bypassed around Allatoona. Johnston’s Confederates held a line anchored on the heights of Brush Mountain with a bulge in the center to include Pine Mountain, from which Rebel officers could survey every move Sherman’s forces made. Despite the progress of his armies, the red-bearded Union general was frustrated that he had not been able to trap Johnston’s army or bring it to battle in the open field. On June 14 as he studied Pine Mountain through his field glasses, he was annoyed to see a cluster of gray-clad officers on the mountaintop serenely scrutinizing his positions. “How saucy they are,” he exclaimed in disgust, and turning to a subordinate he ordered him to have a battery open up on the summit and at least make the cheeky Rebels take cover.

The Union gunners already had the range. Indeed, the main goal of Union operations for the day or two before had been to find artillery positions from which the crest of Pine Mountain could be taken in crossfire and made untenable. How close they had already come to doing so was demonstrated by the identities of the officers Sherman had seen, though he could not have recognized them at that distance. Hardee had recommended to Johnston the evacuation of the mountain, and the two had come to survey the terrain in person, with Polk tagging along. The Union gunners’ first round was a near miss, and Johnston ordered the group to scatter and take cover. A second shell exploded closer still as Johnston and Hardee scurried for safety and Polk paced solemnly away with the dignity befitting a lieutenant general and an Episcopal bishop. The third round struck him squarely, killing him instantly.