There is No Alternative (28 page)

Read There is No Alternative Online

Authors: Claire Berlinski

The relationship between the United States and Britain became closerâAmericans love a winnerâresulting in a more confrontational policy toward the Soviet bloc, a period known now as the Second Cold War. On June 23, little more than a week after the surrender of the Argentines, Thatcher traveled to New

York to address the General Assembly of the United Nations, which had gathered for a special session on disarmament. “There is,” she said,

York to address the General Assembly of the United Nations, which had gathered for a special session on disarmament. “There is,” she said,

a natural revulsion in democratic societies against war and we would much prefer to see arms build-ups prevented, by good sense or persuasion or agreement. But if that does not work, then the owners of these vast armouries must not be allowed to imagine that they could use them with impunity.

But mere words, speeches and resolutions will not prevent them. The security of our country and its friends can be ensured only by deterrence and by adequate strengthâadequate when compared with that of a potential aggressor.

138

138

Â

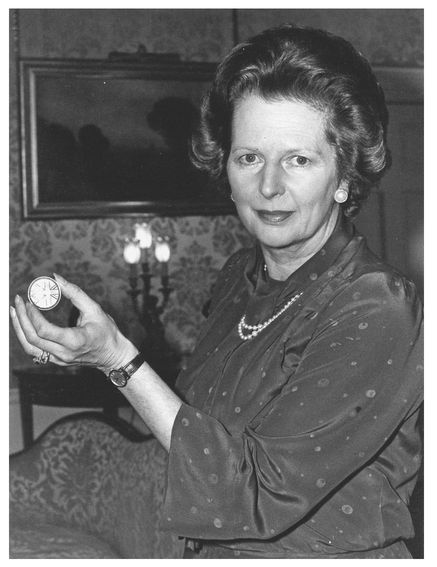

Margaret Thatcher is presented with a commemorative coin to celebrate the Falklands victory. “We adored her,” recalled Major General Julian Thompson, Brigade Commander during the Falklands war, “and would have done anything for her. In all my years' service, I have never seen anything like it . . . we all loved her for her calmness . . . her enthusiasm, and dare one say it, because she is an extremely handsome lady. We appreciated that, too.”

(Central Office of Information)

(Central Office of Information)

These words clearly conveyed to the Soviet Union a great deal more seriousness than they would have had Thatcher not recently proven herself preparedâto the point of recklessnessâto live by them.

Galtieri was placed under house arrest on June 18. He was convicted of mishandling the war, stripped of his rank, and imprisoned. The junta collapsed.

In one of those strange twists of fate suggesting that if nothing else, the Master of the Universe has a fine sense of irony, it now appears that the Falklands just

might

be sitting above a hundred billion barrels of oil. Recent technological advances in deep-sea exploration, specifically the development of controlled-source electromagnetic surveying, have led investors to wonder if the Falklands could be rather more valuable than they look. They have found nothing yet, but if their theory proves correct, the islanders will become the wealthiest people in the world. I stress that this was not suspected at the time and could not reasonably have been suspected: The relevant technology had not yet been invented.

might

be sitting above a hundred billion barrels of oil. Recent technological advances in deep-sea exploration, specifically the development of controlled-source electromagnetic surveying, have led investors to wonder if the Falklands could be rather more valuable than they look. They have found nothing yet, but if their theory proves correct, the islanders will become the wealthiest people in the world. I stress that this was not suspected at the time and could not reasonably have been suspected: The relevant technology had not yet been invented.

There is a nice story about the penguins. Some 25,000 land mines, mostly planted by the Argentineans, remain in the no-go areas of the Falklands. Fortunately, the penguins are too light to set them off. But the presence of the mines has ensured that the area is now a conservation zone, one where harsh penalties await those

tempted to violate its integrity. The squawking penguins waddle about happily; conservationists are delighted by the protection of lands that had previously been overgrazed by sheep. There is a suspicion that other forms of bird and amphibious life have similarly profited, but no one is quite sure to what degree. As the director of Falklands Conservation, Grant Munro, remarked, “It has really not been looked into, for obvious reasons.”

tempted to violate its integrity. The squawking penguins waddle about happily; conservationists are delighted by the protection of lands that had previously been overgrazed by sheep. There is a suspicion that other forms of bird and amphibious life have similarly profited, but no one is quite sure to what degree. As the director of Falklands Conservation, Grant Munro, remarked, “It has really not been looked into, for obvious reasons.”

7

Coal and Iron

We had to fight the enemy without in the Falklands. We always have to be aware of the enemy within, which is much more difficult to fight and more dangerous to liberty.

âTHATCHER ON THE MINERS' STRIKE

Orgreave, South Yorkshire, June 18, 1984. It is blisteringly hot. Many of the striking miners are shirtless, dripping with sweat. Not so the police, mounted on horseback and dressed head-to-toe in black battle gear.

It begins in a field near the British Steel coking plant.

BBC News: Arthur Scargill called for a mass picket of Orgreave. Today, he got one.

The sky is bright blue. ScargillâKing Arthur, they call himâstruts past the massed ranks of miners, directing them with a bullhorn.

Maggie, Maggie, Maggie, out, out, out! The miners, united, will never be defeated!

BBC News: Arthur Scargill called for a mass picket of Orgreave. Today, he got one.

The sky is bright blue. ScargillâKing Arthur, they call himâstruts past the massed ranks of miners, directing them with a bullhorn.

Maggie, Maggie, Maggie, out, out, out! The miners, united, will never be defeated!

But MI5 has infiltrated the National Union of Mineworkers, and the police know what Scargill has in mind even before he calls the orders. Ambulances are standing by. The cops pen the picketers

away from the entrance to the plant. When the strikers spot the convoy of approaching trucks, a rumble passes through the crowd. Then they surge.

Here we go, here we go!

The air vibrates with the sound of shouting, police whistles, barking dogs. The phalanx of black-clad policemen runs directly into the scrum. They take on the miners in hand-to-hand combat. The horses charge. The miners throw missiles and rip up fencingâthey throw that, too. Cloudbursts from smoke bombs turn the air bright red.

London calling to the faraway towns . . . Now war is declared, and battle come down . . .

away from the entrance to the plant. When the strikers spot the convoy of approaching trucks, a rumble passes through the crowd. Then they surge.

Here we go, here we go!

The air vibrates with the sound of shouting, police whistles, barking dogs. The phalanx of black-clad policemen runs directly into the scrum. They take on the miners in hand-to-hand combat. The horses charge. The miners throw missiles and rip up fencingâthey throw that, too. Cloudbursts from smoke bombs turn the air bright red.

London calling to the faraway towns . . . Now war is declared, and battle come down . . .

The reinforcements arrive, brandishing massive riot shields. They hold the miners back, grabbing miners at random and shoving them into pig buses.

The trucks sweep in procession into the plant.

The pickets counter with a second push. The police call in the snatch squads: Modeled on the colonial riot policeâin turn modeled on the Roman legionsâthe snatch squads have never before been deployed on the British mainland. An officer gives them their orders:

You know what you're doing. No heads, bodies only!

You know what you're doing. No heads, bodies only!

The picketers begin throwing ball bearings, rocks. They hit an officer in the face; he clutches his bloody nose. The snatch squads bear down on their horses, cantering straight into the mass of men, beating the miners with truncheons. Panic sweeps the crowd. The miners have blood streaming from their

head

wounds: There is no doubt about that.

head

wounds: There is no doubt about that.

At last the cavalry drives the miners back behind the police line. The ambulances burn off, sirens warbling. One hour and twenty minutes later, the trucks leave the plant, laden with the coal and scabby labor they came to collect. The picketing miners, helpless behind the police cordon, stand and watch in almost total silence.

After this some of the miners shuffle off to the pub for a beer, dispirited. It is a red-hot day. But the die-hards stay on the lines. By afternoon, the police have been sweltering in the sun for far too long. The remaining picketers have been taunting them; the

cops are tired, hot, thirstyâthey begin banging their shields with their truncheons. What happens next? No one agrees. Round two is worse than round oneâmuch worse. Police boots smash into the shins of the picketers. “

Get bloody off!

” “

Shut your fucking mouth, or I'll break your fucking neck!

”

139

cops are tired, hot, thirstyâthey begin banging their shields with their truncheons. What happens next? No one agrees. Round two is worse than round oneâmuch worse. Police boots smash into the shins of the picketers. “

Get bloody off!

” “

Shut your fucking mouth, or I'll break your fucking neck!

”

139

Miners flee across the field and the railway tracks, but the cops close in, beating them even after they fall, unconscious, to the ground. Then to the astonishment of the village's residents, the miners run into Orgreave itself and the cavalry gallops right after them. The miners fight back with scrap-metal missiles. Enraged, the cops charge themâas well as the assembled onlookersâthrough the terraced streets of the town. The miners improvise barricades; they mount a contraption with a stake to impale the horses. One miner is slammed repeatedly against the hood of a car; the cops stamp on his leg, breaking it, then arrest him and drag him back, on one foot, behind the police lines.

London calling, see we ain't got no swing . . . 'Cept for the ring of that truncheon thing . . .

Weirdly, amid the chaos, the Rock On Tommy ice-cream van keeps selling ice cream until it is completely enclosed by the cavalry.

London calling, see we ain't got no swing . . . 'Cept for the ring of that truncheon thing . . .

Weirdly, amid the chaos, the Rock On Tommy ice-cream van keeps selling ice cream until it is completely enclosed by the cavalry.

Twelve years before, the miners had forced Ted Heath's government to surrender by picketing the Saltley coke depot in Birmingham. Scargill was a senior figure in the Yorkshire branch of the miners' union then. He innovated the tactic of using flying picketsâdispatching shock troops of strikers from the most militant areas of Britain to the scene of the dispute. Most of the picketers who shut down the Saltley plant were not even employed there. The tactic was devastatingly effective. The event made Arthur Scargill into a hero among miners and a household name. In 1974, using the same tactics, Scargill brought down the Heath government.

Now Scargill is the president of the National Union of Mineworkers. Thatcher is determined that Orgreave will not be a repeat performanceâno matter what it takes.

Soon the image will be broadcast from Orgreave to every British household with a television: a disheveled Arthur Scargill, clutching his baseball cap as he is dragged off by the police. He is telling anyone who will listen that Britain has been turned into some kind of Latin American junta. “1984âGreat Britain!” he shouts to reporters.

BBC News:

This time Scargill seems to have failedâthe 34 lorry drivers today managed to make two journeys unhindered and say they are determined to continue the coke runs.

This time Scargill seems to have failedâthe 34 lorry drivers today managed to make two journeys unhindered and say they are determined to continue the coke runs.

The day after, in the House of Commons:

The Prime Minister:

However serious the strikeâand it is seriousâthe consequences of giving in to mob rule would be far graver . . .

Mr. Kinnock:

Will the Prime Minister tell us why she wants this chaos, conflict and cost to go on rising? [

Hear! Hear! Rumbling and jeers.

] . . .

The Prime Minister:

The right hon. Gentleman . . . knows full well that what we saw there was not peaceful picketing, but mob violence and intimidation. I am astonished that he should suggest that, because one faction of the National Union of Mineworkers adopts these disgraceful tactics, it should be given what it wants! [

Hear! Hear!

] . . .

Mr. Kinnock:

If the right hon. Lady expended a fraction of the energy that she gives to political posturing on trying to promote a settlement, we would have ended the strike by now! . . .

The Prime Minister:

I note that the right hon. Gentleman referred to mob rule as political posturing. I can say to him only that whatever government are answering from the Dispatch Box, if they gave in to mob rule, that would be the end of liberty and democracy . . .

Mr. Kinnock:

That was

not an answer; it was a recitation of arrogant complacency, an evasion, and a betrayal of the national interest! [

Interruption, roaring.

]

The Prime Minister:

The right hon. Gentleman, who is shouting and posturing, is more accustomed to it than I am. We have seen violence which he has notâ[

Interruption, loud shouting.

]

Mr. Speaker:

Order! There is so much noise that the Prime Minister did not hear that I called Question No. 2! . . .

Mr. Redmond:

Will the Prime Minister inform the House when she has sufficient blood on her hands to satisfy her hatred of the miners? . . .

140

However serious the strikeâand it is seriousâthe consequences of giving in to mob rule would be far graver . . .

Mr. Kinnock:

Will the Prime Minister tell us why she wants this chaos, conflict and cost to go on rising? [

Hear! Hear! Rumbling and jeers.

] . . .

The Prime Minister:

The right hon. Gentleman . . . knows full well that what we saw there was not peaceful picketing, but mob violence and intimidation. I am astonished that he should suggest that, because one faction of the National Union of Mineworkers adopts these disgraceful tactics, it should be given what it wants! [

Hear! Hear!

] . . .

Mr. Kinnock:

If the right hon. Lady expended a fraction of the energy that she gives to political posturing on trying to promote a settlement, we would have ended the strike by now! . . .

The Prime Minister:

I note that the right hon. Gentleman referred to mob rule as political posturing. I can say to him only that whatever government are answering from the Dispatch Box, if they gave in to mob rule, that would be the end of liberty and democracy . . .

Mr. Kinnock:

That was

not an answer; it was a recitation of arrogant complacency, an evasion, and a betrayal of the national interest! [

Interruption, roaring.

]

The Prime Minister:

The right hon. Gentleman, who is shouting and posturing, is more accustomed to it than I am. We have seen violence which he has notâ[

Interruption, loud shouting.

]

Mr. Speaker:

Order! There is so much noise that the Prime Minister did not hear that I called Question No. 2! . . .

Mr. Redmond:

Will the Prime Minister inform the House when she has sufficient blood on her hands to satisfy her hatred of the miners? . . .

140

I meet Lord Peter Walker, who served as Thatcher's energy secretary during the miners' strike, for lunch at the Carlton Club in London. This is the club that reluctantly declared Thatcher an honorary gentleman. Thatcher surveys the foyer from her portrait; a massive bronze bust of her head presides above the staircase. When I ask the porter where to find the ladies' cloakroom, he nods in the direction of the bust: “Turn left past Margaret, Madame.” Upstairs is the Wellington Room, where members are permitted to entertain their lady friends. This is where I dine with Lord Walker. Beyond is the Churchill Roomâfor members onlyâwhich of course I do not see, for I am not a gentleman, even of the honorary kind.

Other books

Collected Fictions by Gordon Lish

Christmas With Wolves (Werewolf Couple Erotic Romance) by Verity Rayne

The Dom Prize (The Dominants by Moore, Mina J.

Mistress of the Catacombs by Drake, David

Nowhere to Run by Saxon Andrew

To Summon a Demon by Alder, Lisa

Apocalypse Atlanta (Book 4): Apocalypse Asylum by Rogers, David

Bejeweled and Bedeviled by Tiffany Bryan

Gabriel David's White Horse by Gina Watson

Four Degrees Celsius by Kerry Karram