Theory of Fun for Game Design (19 page)

Read Theory of Fun for Game Design Online

Authors: Raph Koster

Tags: #COMPUTERS / Programming / Games

Games do not need to be able to evoke an unexpected tear, like the

Pietà

.

Games do not need to be able to rouse us to anger against injustice, like

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

.

Games do not need to be able to send us spiraling into awe, like Mozart’s

Requiem

.

Games do not need to leave us hovering at the boundary of understanding, like Duchamp’s

Nude Descending a Staircase

.

Games do not need to record the history of our souls, like

Beowulf

.

They may not be able to, in fact. We would not necessarily ask architecture or dance to accomplish all of those things either.

But games

do

need to illuminate aspects of ourselves that we did not understand fully.

Games do need to present us with problems and patterns that do not have one solution, because those are the problems that deepen our understanding of ourselves.

Games do need to be created with formal systems that have authorial intent.

Games do need to acknowledge their influence over our patterns of thought.

Games do need to wrestle with the issues of social responsibility.

Games do need to attempt to apply our understanding of human nature to the formal aspects of game design.

Games do need to develop a critical vocabulary so that understanding of our field can be shared.

Games do need to push at the boundaries.

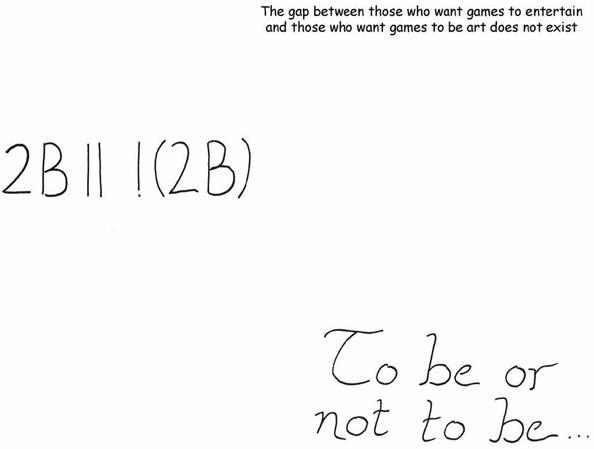

Most importantly, games and their designers need to acknowledge that there is no distinction between art and entertainment. Viewed in context with human endeavor and what we know of how our inner core actually

works

, games are not to be denigrated. They are not trivial, childish things.

In no other medium do the practitioners assume that just because they’re paying their dues, they cannot create something capable of changing the world. Nor should game designers.

All art and all entertainment are posing problems to the audience. All art and all entertainment are prodding us toward greater understanding of the chaotic patterns we see swirl around us. Art and entertainment are not terms of

type

—they are terms of

intensity

.

Why? Because people are lazy, yet people also want a better life for their children. That is the blind urge that drives all humanity, all life. A legacy is what motivates the selfish genes embedded in the warp and weft of our bodies.

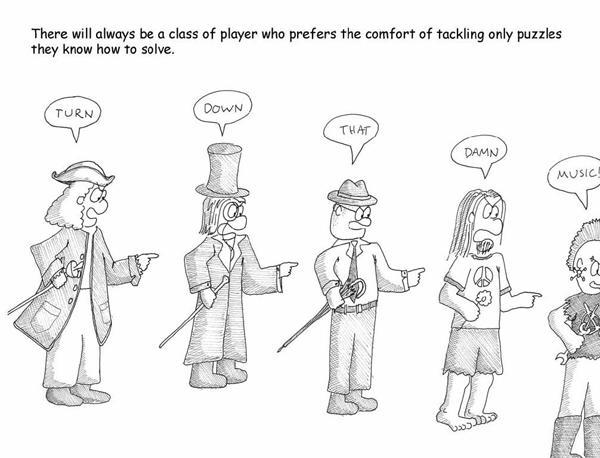

Let’s be frank with ourselves. We all know that most people, most of the audience out there, is complacent. They are very willing to settle for easy entertainment. They are more than up for another evening in the Barcalounger in front of a sitcom that teaches the same lessons that the one on last week did.

We call this “pop music.” We call it “mass market.” And games are indeed reaching for this mass market, and I suppose that to a degree I am fighting in the tide in arguing that that is not the ultimate destiny for games any more than it is for any other art form. The art we remember is material that opened up new vistas; whether or not it was popular at the time is largely an accident of history. Shakespeare was a popular playwright and then was forgotten for a couple hundred years. Popularity is not a measure of long-term evolutionary success.

A tremendous amount of the content pumped through media today has as its goal mere comforting, confirming, and cocooning. We gravitate toward the music we already like, the morals we already know, the characters who behave predictably.

Seen in the most pessimistic light, this is irresponsible. When the world shifts around those people, they will lack the tools to adapt. The calling of the creator is to provide those people with the tools to adapt, so that when the world changes and is swept along the currents of cultural change, those folks in the Barcaloungers are swept along with them and the march of human advancement continues.

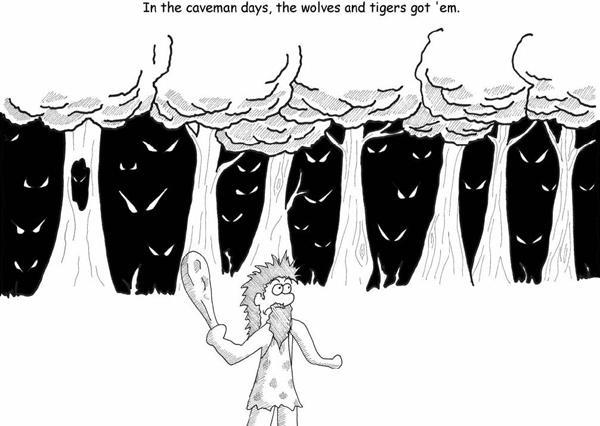

Play developed to teach us about survival. For many cultural reasons, we have allowed it to take a place in human culture where it is denigrated, minimized, and assumed to be worthless. And yet there’s a cultural undercurrent that operates at the instinctive level, an under-current that mourns the ways in which play is removed from our lives.

Games mattered to us in prehistoric days. It may be that we’ve outgrown the simplistic lessons they were able to teach and that, when we reach adulthood, we do in fact put aside childish ways.

But my kids are showing me that childhood is also a state of mind. It is an ongoing quest for learning.

I, for one, don’t want to put that aside, and I don’t think anyone else should either.

In the end, if I can say with a straight face after a day’s work making games that one person out there learned to be a better leader, a better parent, a better co-worker; learned a new skill that kept them their job, a new skill that helped them advance the state of the art in their chosen field, a new skill that made their world grow a little…

Then I will know that my work was valuable. It was worthwhile. It was a contribution to society.

I’ll be able to whisper to myself, “I do connect people.”

“I do teach.”

Hear that, grandpa?

I MAKE GAMES, AND IM PROUD OF IT.

It’s been a long journey for me, and I don’t doubt that as my kids continue to grow, it will seem even longer.

I have watched them start to learn the concepts of respect for one another.

I have watched them understand that resources are limited and that things must be shared.

Every day, they connect an astounding number of new neurons; they learn a flabbergasting number of new words, and they develop in ways I can barely remember and barely glimpse.

Games are helping them along that path, and for that I am grateful. I’m not immune to the desire that my children be better off, after all, and I’ll take any tool that helps us along that path.

A lot of old age is attributable to losing neurons, losing connections, losing the patterns we have built up, settling into fewer and fewer until all we can do is stand by helplessly as the world dissolves into noise around us. We’d all be better off if we kept our minds limber by pushing them to always tackle new problems.

Not too long before my grandfather died, he told me, “I’m thinking of getting one of those computer things. It doesn’t seem like the Internet is all that different from ham radio. Maybe I’ll give it a try.”

I learned of my grandfather’s passing when I arrived at the hotel in San Jose, where I was attending the annual Game Developers Conference. Somehow it seems apropos.

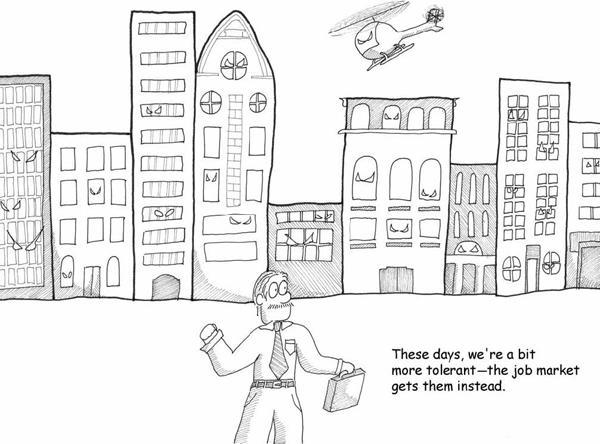

The questions he posed, there in the wake of shootings at Columbine High School, there at a time when the world was suddenly making little sense, are fair questions.

Are games a tool for evil? Or for good? Are they frivolous at best or frivolous at worst?

It seems important that we know the answers, not just to allow those of us who work in this field to sleep better at night, but also in order to reassure those who watch us work: our families, our friends, our cultures.

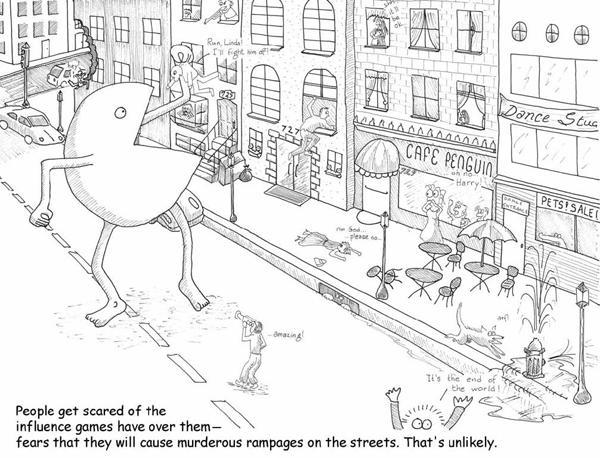

Games fit in the spectrum of human activity. Human activity is not always pretty. It’s not always noble. It’s not always altruistic. And a lot of really dumb things are done in games. A lot of dumb things are done by people playing games. A lot of dumb things are done by those making games.

But ignorance can be rectified. Human activity may be driven by selfish genes, by the phantasms of inaccurate perception, by reactionary tribalism and shortsighted dominance moves.

But there are those firemen, those special education teachers, those architects, who are out there working. They’re building spaces in which we can live safely and rear our children.

I’ve put forth what may seem like a mechanistic view of the world in this book, one that would perhaps run contrary to my grandfather’s deeply held religious faith. And yet I think that we would both come to the same conclusion:

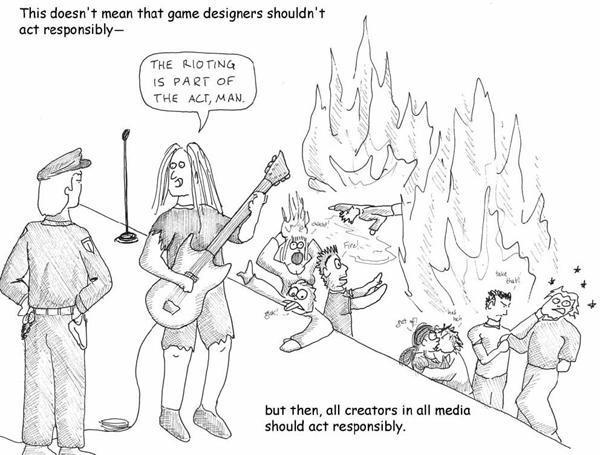

Any striving for understanding that we do is likely to hold back the darkness. The new may scare us, as when symphonies with odd harmonies cause riots among disturbed music lovers…

But time smoothes things over. And we are left with beautiful music.

So my answer here is, I am willing to choose which side of human nature I want to foster.

I cannot blame my grandfather for being nervous about something that seemed very new, even though it was in fact very old. It is a natural reaction. It is the human reaction to the eruption of the unfamiliar.

Tracing the nature of fun, and the core of gameplay, has made me more comfortable in my own self with what I do, and why I do it.

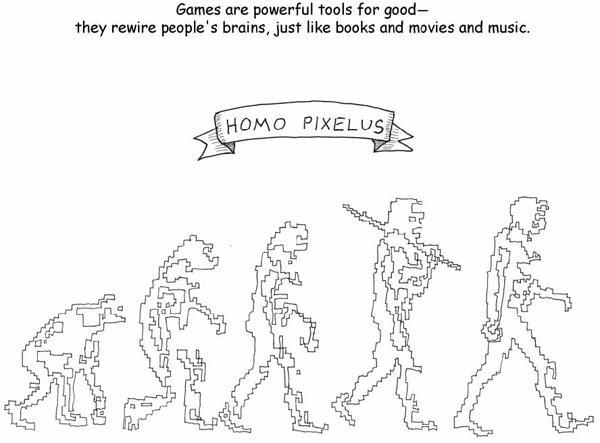

We have a powerful tool here, one that is arguably underutilized even as it reaches new peaks of acceptance among people of all ages. We should take it up responsibly, with awareness of how it fits into culture, and with respect for its abilities.

The mere titling of a piece of music lends it narrative context and enriches it tremendously. Yes, it is possible to appreciate Penderecki’s

Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima

or any of the works of Aaron Copland without their titles, as pure sound. But the

sense

of them is carried in the interstices between the music and the title. Just as the

sense

of a film is carried in the webbing between the acting and the writing and the cinematography.

Other art forms have long recognized this; Welles’s staging of

Macbeth

as a Haitian tale of vodoun, for example, achieved by selectively adjusting one of the component pieces of the art form.

All of which is by way of saying that I don’t think we get to ignore the prostitutes, the sexism, the occasional racism, and the general crudity of the commercial game industry. The prostitute in

Grand Theft Auto

may be a power-up in mechanical terms. But in experiencing the game, it takes a game critic to divorce her from the context in which she appears. And frankly, game critique isn’t even developed enough to give that particular game object and interaction a name.

My answer here is, I’m content with accepting my responsibility on that front.

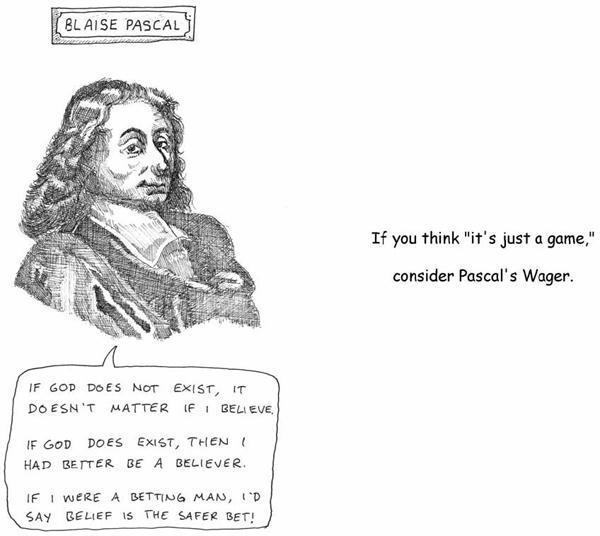

If games are mere amusements, and my grandfather’s concerns were valid, then by acting responsibly, and striving to make games that illuminate the human condition, I have at least caused no harm.

If I am going to noodle about with this medium simply because I think it’s a nifty keen toy, the

least

I can do is make sure I don’t hurt anyone else in the process. Even better, I can take this nifty keen toy very very very seriously and assume that it is a powerful tool for good or evil. And try to make it a tool for good.

It’s Pascal’s Wager. If it’s all “just a game,” I was just a crackpot all along. But if it’s not…. There are only two responsible ways to behave with such a tool. Either step away from it altogether and let someone qualified take it up, or take it up and be as qualified as you can.

My reply is, I won’t take a sucker bet.

The task I have to make my grandfather proud of what I do seems fairly simple, really. It’s not that dissimilar to the role he took up each time he picked up his carpentry tools in his workshop.

Work hard on craft.

Measure twice, cut once.

Feel the grain; work with it, not against it.

Create something unexpected, but faithful to the source from which it sprang.

Strikes me as good advice for any act of creation. My reply is, I can do that.

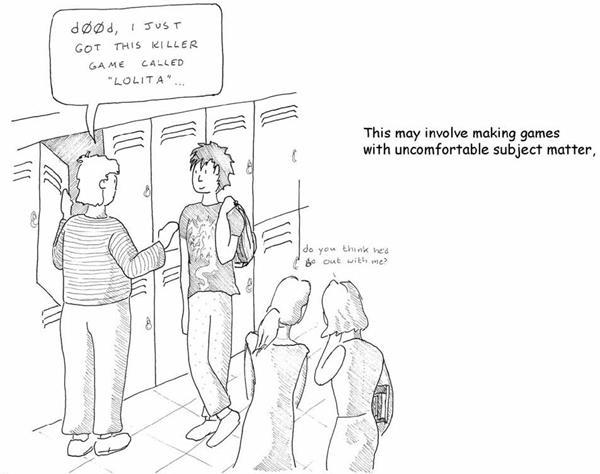

My kids already play games and say things and do things that make me uncomfortable, just as I made games that made my grandfather uncomfortable. Some eggs need to be broken to make this omelet.

To achieve the potential of the medium, we’re going to have to push at some boundaries and on some buttons that may make people rather uncomfortable. We’ll assert that games are not only entertainment, and we will probably produce some work that may shock, or offend, or present themes that challenge deeply cherished beliefs.

That’s not outlandish. All the other media do it.

My commitment is, I’ll try to make sure that nobody gets hurt.

For all of us game designers, it means the extremely difficult task of reevaluating our roles in life. It means perceiving ourselves as having a responsibility to others, whereas we previously thought of ourselves as carefree. It means granting a greater level of respect to the tools we work with—the push and pull of mechanic and feedback, the intricate pathways of the human brain and human apprehension—and a greater level of respect to our audience.