Theory of Fun for Game Design (16 page)

Read Theory of Fun for Game Design Online

Authors: Raph Koster

Tags: #COMPUTERS / Programming / Games

Some folks disagree with me pretty vehemently on this. They feel that the art of the game lies in the formal construction of systems. The more artfully constructed the system is, the closer the game is to art.

Putting games in context with other media demands that we consider this viewpoint. In literature, it’s called a

belles-lettristic

point of view. The beauty of poetry lies solely in the sound and not in the sense, according to those who feel this way.

And yet, even the shape of the sound can be put in context. Let’s digress and consider some other media…

Impressionism is not concerned with giving impressions, but rather with a more distanced form of seeing, of mimesis. Modern image processing tools describe the Impressionist formal process (and indeed many of the later processes such as posterization) as

filters

—an accurate description in that Impressionist paintings are depictions not of an object or a scene, but of the play of light upon said object or scene. In such representations, you still must conform to all previously established rules of composition—color weight, balance, vanishing point, center of gravity, eye center, and so on—while essentially avoiding painting the object or scene itself, which ends up being absent from the finished work.

Impressionist music was based primarily on repetition; its influence on later minimalist styles is clear. However, where minimalism also restricts its harmonic vocabulary, often to just a few essential chords (tonic, dominant, subdominant, perhaps a few extensions or substitutions thereof), Impressionist music is essentially that of Debussy: intensely varied in orchestration, extremely complex, particularly in its chromatic harmonies, and nonetheless very repetitive melodically. Ravel’s work as an orchestrator is perhaps the epitome of the Impressionistic style: his “Bolero” consists of the same passage played over and over, identical harmonically and melodically; it has merely been orchestrated differently at each repetition, and the dynamics are different. The sense of crescendo throughout the piece is achieved precisely though this repetition.

And of course, there was “Impressionist” writing. Virginia Woolf, Gertrude Stein, and many other writers worked with the idea that characters are unknowable. Books like

Jacob’s Room

and

The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas

play with the established notions of self and work toward a realization that other people are essentially unknowable. However, they also propose an alternate notion of knowability: that of “negative space,” whereby a form is understood and its nature grasped by observing the perturbations around it. The term is from the world of pictorial art, which provides many useful insights when discussing the problem of mimesis.

All of these are organized around the same principles; that of negative space, that of embellishing the space around a central theme, of observing perturbations and reflections. There was a zeitgeist, it is true, but there was also conscious borrowing from art form to art form, and it occurs in large part because no art form stands alone; they bleed into one another.

Can you make an Impressionist game? A game where the formal system conveys the following?

- The object you seek to understand is not visible or depicted.

- Negative space is more important than shape.

- Repetition with variation is central to understanding.

The answer is, of course you can. It’s called

Minesweeper

.

In the end, the endeavor that games engage in is not at all dissimilar to the endeavors of any other art form. The principal difference is not the fact that they consist of formal systems. Look at the following lists:

- Meter, rhyme, spondee, slant rhyme, onomatopoeia, caesura, iamb, trochee, pentameter, rondel, sonnet, verse

- Phoneme, sentence, accent, fricative, word, clause, object, subject, punctuation, case, pluperfect, tense

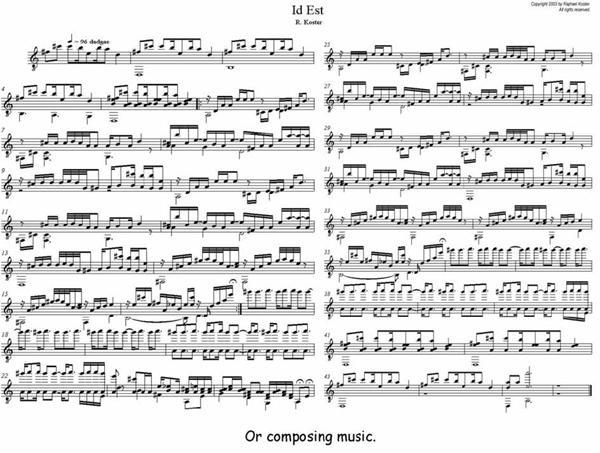

- Meter, fermata, key, note, tempo, coloratura, orchestration, arrangement, scale, mode

- Color, line, weight, balance, compound, multiply, additive, refraction, closure, model, still life, perspective

- Rule, level, score, opponent, boss, life, power-up, pick-up, bonus round, icon, unit, counter, board

Let’s not kid ourselves—the sonnet is caged about with as many formal systems as a game is.

If anything, the great irony about games, put in context with other media, is that they may afford less scope to the designer, who has less freedom to impose, less freedom to propagandize. Games are not good at conveying specifics, only generalities. It is easy to make a game that tells you that small groups can prevail over large ones, or the converse. And that may be a valuable and deeply personal statement to make. It’s a lot harder to make a game that conveys the specific struggle of a group of World War II soldiers to rescue one other man from behind enemy lines, as the film

Saving Private Ryan

does. The designer who wants to use game design as an expressive medium must be like the painter and the musician and the writer, in that they must learn what the strengths of the medium are, and what messages are best conveyed by it.

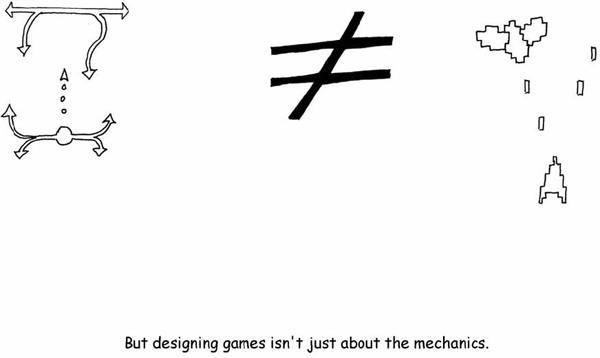

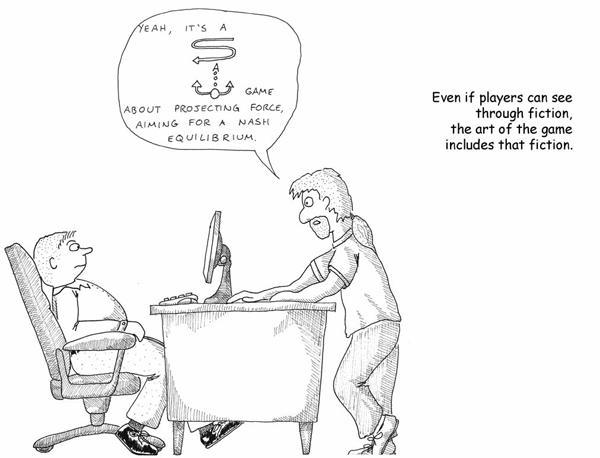

Nobody actually interacts with games on an abstract level exclusively. You don’t play the abstract diagrams of games that I have drawn on the facing pages; you play the ones that have little spaceships and laser bolts and things that go Boom. The core of gameplay may be about the emotion I am terming “fun,” the emotion that is about learning puzzles and mastering responses to situations, but this doesn’t mean that the other sorts of things we lump under fun do not contribute to the overall experience.

People like playing go using well-burnished beads on a wooden board and they like buying

Lord of the Rings

chess sets and glass Chinese checkers sets. The aesthetic experience of playing these games matters. When you pick up a well-carved wooden game piece, you respond to it in terms of aesthetic appreciation—one of the other forms of enjoyment. When you play table tennis against an opponent, you feel visceral sensations as you stretch your arm to the limit and smash the ball against the table surface. And last, when you slap the back of your teammate, congratulating him on his field goal, you’re participating in the subtle social dance that marks the constant human exercise of social status.

We know this about other media. It matters who sings a song because delivery is important. We treasure nice editions of books, rather than cheap ones, even though the semantic content is identical. Rock climbing a real rock face, versus a fake one attached to a wall, feels different.

In many media, the presentation factors are outside the hands of the initial creator of the content. But in other media, the creator has a say. Often, we have a specific person whose role it is to create the overall experience as opposed to the content itself. And rightfully, this person is given higher authority over the final output than the content creator alone. The director trumps the writer in a movie, and the conductor trumps the composer in a symphony.

There is a difference between designing the content and designing the end-user

experience

.

In most cases, we haven’t reached this realization in game design. Game design teams are not set up this way. Nonetheless, it’s an inevitable development in the medium. Too many other components have tremendous importance in our overall experience of games for their overall shape to rest in the hands of the designer of formal abstract systems alone.

Players see through the fiction to the underlying mechanics, but that does not mean the fiction is unimportant. Consider films, where the goal is typically for the many conventions, tricks, and mind-shapings that the camera performs to remain invisible and unperceived by the viewer. It’s rare that a film tries to call attention to the gymnastics of the camera, and when it does, it will likely be to make some specific point. There are many techniques used by the director and the cinematographer, such as framing the shot of a conversation from slightly over the shoulder of the interlocutor to create a sense of psychological proximity, that are used transparently, without the viewer noticing, because they are part of the vocabulary of cinema.

For better or worse, visual representation and metaphor are part of the vocabulary of games. When we describe a game, we almost never do so in terms of the formal abstract system alone—we describe it in terms of the overall experience.

The dressing is tremendously important. It’s very likely that chess would not have its long-term appeal if the pieces all represented different kinds of snot.

When we compare games to other art forms that rely on multiple disciplines for effect, we find that there are a lot of similarities. Take dance, for example. The “content creator” in dance is called the choreographer (it used to be called the “dancing master,” but modern dance disliked the old ballet terms and changed it). Choreography is a recognized discipline. For many centuries, it struggled, in fact, because there was no notation system for dance. That meant that much of the history of this art form is lost to us because there was simply no way to replicate a dance save by passing it on from master to student.