The Wolves of Willoughby Chase (18 page)

Read The Wolves of Willoughby Chase Online

Authors: Joan Aiken

‘No, miss,’ said James firmly. ‘I obey some of your orders because I’ve got no alternative, but help to put children in those dungeons I can’t and won’t. It’s not Christian.’ And he left the room, shutting the door sharply behind him.

‘I’ll get the keys, Letitia,’ said Mrs Brisket, rising ponderously. ‘You can be administering chastisement, meanwhile.’

Miss Slighcarp came down from her platform. ‘Miss Green,’ she said, and her eyes were so glittering with fury that even Bonnie quailed, ‘put out your hand.’

Bonnie took a step backward. Miss Slighcarp followed her, and raised the pointer menacingly. The children at the desks drew a tremulous breath. But just as the pointer came swishing down, the chimneypiece panel flew open, and Mr Gripe, stepping out, seized hold of Miss Slighcarp’s arm.

For a moment she was utterly dumbfounded. Then, in wrath she exclaimed:

‘Who are you, sir? Let me go at once! What are you doing in my house?’

‘In your house, ma’am? In

your

house? Don’t you remember me, Miss Slighcarp?’ said Mr Gripe. ‘I was the attorney instructed by your distant relative, Sir Willoughby Green, to seek you out and offer you the position of instructress to his daughter. You brought with you a testimonial from the Duchess of Kensington. Don’t you remember?’

Miss Slighcarp turned pale.

‘And who gave you permission, woman,’ suddenly thundered Mr Gripe, ‘to turn this house into a boarding school? Who said you could use these children with villainous cruelty, beat them, starve them, and lock them in dungeons? Oh, it’s no use to protest, I’ve been behind that panel and heard every word you’ve uttered.’

‘It was only a joke,’ faltered Miss Slighcarp. ‘I had no intention of really shutting them in the dungeons.’

At this moment Mrs Brisket re-entered the room holding a bunch of enormous rusty keys.

‘We can’t use the upper dungeons, Letitia,’ she began briskly, ‘for Lucy and Emma are occupying them. I have brought the lower …’

Then she saw Mr Gripe, and behind him the two Bow Street officers. Her jaw dropped, and she was stricken to silence.

‘Only a joke, indeed?’ said Mr Gripe harshly. ‘Mr Cardigan, place these two females under arrest, if you please. Until it is convenient to remove them to jail, you may as well avail yourself of the dungeon keys so obligingly put at your disposal.’

‘You can’t do this! You’ve no right!’ shrieked the enraged Miss Slighcarp, struggling in the grip of Cardigan. ‘I have papers signed by Sir Willoughby empowering me to do as I please with this property in the event of his death, and appointing me guardian of the children – ’

‘Papers signed by Sir Willoughby. Pish!’ said Mr Gripe scornfully. ‘You may as well know, ma’am, that your accomplice Grimshaw, who is already in prison, has confessed to the whole plot.’

At this news all the fight went out of Mrs Brisket,

and

she allowed herself to be manacled by Spock, only muttering, ‘Grimshaw’s a fool, a paltry, whining fool.’

But Miss Slighcarp still gave battle.

‘I tell you,’ she shouted, ‘I saw Sir Willoughby before he departed and he himself left me full powers – ’

At this moment a heavy tread resounded along the passage, and they heard a voice exclaiming:

‘What the

devil’s

all this? Desks, blackboards, carpet taken up – has m’house been turned into a reformatory?’

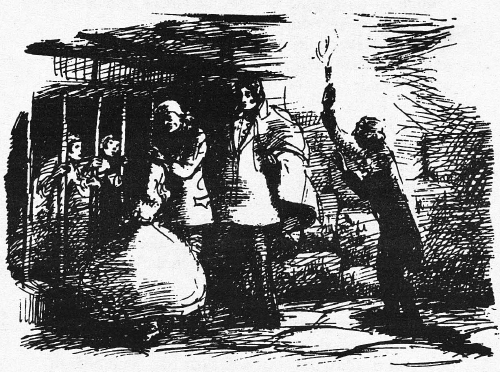

The door burst open and in marched – Sir Willoughby Green! Behind him stood James, grinning for joy.

Bonnie turned absolutely pale with incredulity, stood so for a moment, motionless and wide-eyed, then, uttering one cry –

‘Papa!’

– she flung herself into her father’s arms.

‘Well, minx? Have you missed us, eh? Have you been a good girl and minded your book? I can see you haven’t,’ he said, surveying her lovingly. ‘Rosy as a pippin and brown as a berry. I can see you’ve been out of doors all day long instead of sewing your sampler and learning your

je ne sais quoi

. And Sylvia too – eh, my word, what a change from the little white mouse we left here! Well, well, well, girls will be girls! But what’s all this, ma’am,’ he continued, addressing Miss Slighcarp threateningly, ‘what’s all this hugger-mugger? I never gave you permission to turn Willoughby Chase into a school, no, damme I didn’t! Being my fourth cousin doesn’t give you such rights as that.’

‘But, sir,’ interjected Mr Gripe, who, at first silent with amazement, had now got his breath back, ‘Sir

Willoughby!

This is joyful indeed! We had all supposed you drowned when the

Thessaly

sank.’

Sir Willoughby burst into a fit of laughter.

‘Ay, so they told me at your office! We have been travelling close behind you, Mr Gripe – I visited your place of business yesterday, learned you had just departed for Willoughby, and, since Lady Green was anxious to get back as soon as may be, and relieve the children’s anxiety, we hired a special train and came post-haste after you.’

‘But were you not in the shipwreck then, Sir Willoughby?’

The reply to this question was lost in Bonnie’s rapturous cry – ‘Is Mamma here too?

Is

she?’

‘Why yes, miss, and ettling to see you, I’ll be bound!’

Before the words had left his mouth Bonnie was out of the door. Sylvia, from a nice sense of delicacy, did not follow her cousin. She thought that Bonnie and her mother should be allowed those first few blissful moments of reunion alone together.

Sir Willoughby and Mr Gripe had retired to a corner of the schoolroom and Mr Gripe was talking hard, while Sir Willoughby listened with his blue eyes bulging, occasionally exclaiming, ‘Why damme! For sheer, cool, calm, impertinent effrontery – why, bless my soul!’ Once he wheeled round to his niece and said, is it really true, Sylvia? Did Miss Slighcarp do these things?’

‘Yes, sir, indeed she did,’ said Sylvia.

‘Then hanging’s too good for you, ma’am,’ he growled at Miss Slighcarp. ‘Have her taken to the dungeons, Gripe. When these two excellent fellows

have

breakfasted they can take her and the other harpy off to prison.’

‘Oh sir …’ said Sylvia.

‘Well, miss puss?’

‘May I go with them to the dungeons, sir? I believe there are two children who have been put down there by Miss Slighcarp, and they will be so cold and unhappy and frightened!’

‘Are there, by Joshua! We’ll all go,’ said Sir Willoughby.

Sylvia had never visited the dungeons at Willoughby Chase. They were a dismal and frightening quarter, never entered by the present owner and his family, though in days gone by they had been extensively employed by ancestors of Sir Willoughby.

Down dark, dank, weed-encrusted steps they trod, and along narrow, rock-hewn passages, where the only sound beside the echo of their own footfalls was the drip of water. Sylvia shuddered when she remembered Miss Slighcarp’s expressed intention of imprisoning herself and Bonnie down here.

‘Oh, do let us hasten,’ she implored. ‘Poor Lucy and Emma must be nearly frozen with cold and fear.’

‘Upon my soul,’ muttered Mr Gripe. ‘This passes everything. Fancy putting children in a place like this!’

Miss Slighcarp and Mrs Brisket trod along in the rear of their captors, silent and sullen, looking neither to right nor to left.

The plight of Lucy and Emma was not quite so bad as it might have been. This was owing to the kind-hearted James, who, though he could not release them, had contrived to pass through their bars a number of

warm

blankets and a quantity of kindling and some tapers, to enable them to light a fire, and he had also kept them supplied with food out of his own meagre rations.

But they were cold and miserable enough, and their astonishment and joy at the sight of Sylvia was touching to behold.

Sylvia danced up and down outside the bars with impatience while James found the right key, and then she hurried them off upstairs, without waiting to see Miss Slighcarp locked in their place.

‘Come, come quickly, and get warm by a fire.

Pattern

shall make you a posset – or no, I forget, Pattern is probably not here yet, but I think I know how it is done.’

However, they had no more than reached the Great Hall when they were greeted with an ecstatic cry from Bonnie.

‘Sylvia! Emma! Lucy! Come and see Mamma! Oh, she is so different! So much better!’

They went rather shyly into the salon, where Pattern, who had been summoned by Simon at full gallop on one of the coach-horses, bustled about in joyful tears and served everybody with cups of frothing hot chocolate.

‘Well,’ a gay voice exclaimed, ‘where’s my second daughter?’ And in swept someone whom Sylvia would hardly have recognized for the frail, languid Lady Green, so blooming, beautiful, and bright-eyed did she appear. She embraced Sylvia, cordially made welcome the two poor prisoners, and declared:

‘Now I want to hear all your story, every word, from the very beginning! I am proud of you both – and as for that Miss Slighcarp, cousin of your father’s though she be, I hope she is sent to Botany Bay!’

‘But Aunt Sophy,’ said Sylvia, ‘your tale must be so much more adventurous than ours! Were you not ship-wrecked?’

‘Yes, indeed we were!’ said Lady Green laughing, ‘and your uncle and I spent six very tedious days drifting in a rowing-boat, our only fare being a monotonous choice of grapes or oranges, of which there happened to be a large crate in the dinghy, fortunately for us. We were then picked up by a small and

most

insanitary

fishing-boat

, manned by a set of fellows as picturesque as they were unwashed, who none of them spoke a word of English. They would carry us nowhere but to their home port, which turned out to be the Canary Islands. On

this

boat we received nothing to eat but sardines in olive oil. I am surprised these shocks and privations did not carry me off, but Sir Willoughby maintains they were the saving of me, for from the time of the wreck my health began to pick up. On reaching the Canaries we determined to come home by the next mail-ship, but they only visit these islands every three months or so, and one had just left. We had to wait a weary time, but the peace and the sunshine during our enforced stay completed my cure, as you see.’

‘Oh how glad I am you came home and didn’t go on round the world!’ cried Bonnie.

Sir Willoughby marched in, beaming. ‘Well, well,’ he said, ‘has Madam Hen found her chicks, eh? But as for the state your house is in, my lady, I hardly dare describe it to you. We shall have to have it completely redecorated. And what’s to be done with all these poor orphans?’

‘Oh Papa,’ said Bonnie, bursting with excitement. ‘I have a plan for them!’

‘You have, have you, hussy? What is it, then?’

‘Don’t you think Aunt Jane could come and live in the Dower House, just across the park, and run a school for them? Aunt Jane loves children!’

What, Aunt Jane run a school? At her age?’

‘Aunt Jane is very independent,’ Bonnie said. ‘She wouldn’t want to feel she was living on charity. But she

could

have people to help her –

kind

people. And she could teach the girls beautiful embroidery!’

Lucy and Emma looked so wistful at the thought of this bliss that Sir Willoughby promised to consider it.