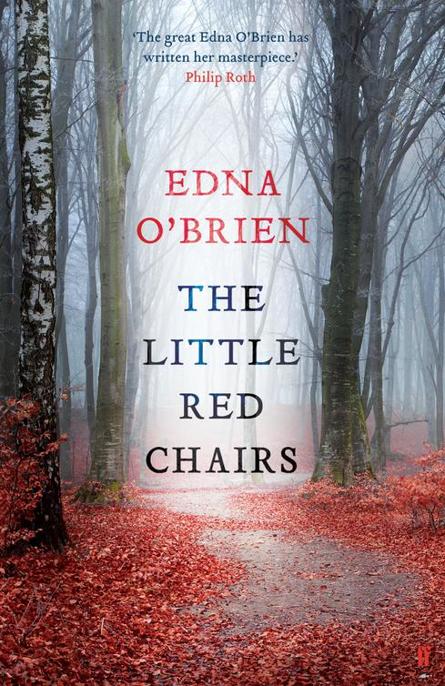

The Little Red Chairs

EDNA O’BRIEN

The Little Red Chairs

WITH

THANKS

Zrinka Bralo

Ed Vulliamy

Mary Martin (aged six)

An individual is no match for history.

ROBERTO BOLAÑO

The wolf is entitled to the lamb.

The Mountain Wreath

(Serbian saga)

On the 6th of April 2012, to commemorate the twentieth anniversary of the start of the siege of Sarajevo by Bosnian Serb forces, 11,541 red chairs were laid out in rows along the eight hundred metres of the Sarajevo high street. One empty chair for every Sarajevan killed during the 1,425 days of siege. Six hundred and forty-three small chairs represented the children killed by snipers and the heavy artillery fired from the surrounding mountains.

Contents

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Author’s note

-

- PART ONE

- Cloonoila

- Fifi

- Men of Faith

- Sister Bonaventure

- Upcock

- On the Veranda

- Into the Woods

- The White Mist

- Dido

- Surfing

- Clouds

- Mujo

- Jack

- Where Wolves Fuck

- Capture

-

- PART TWO

- South London

- Fidelma

- Bluey

- Dust

- The Waiting Room

- Mistletoe’s Father

- The Centre

- Kennels

- A Letter

- James

- Penge

- Sarajevo

-

- PART THREE

- The Courtroom

- The Prison Visit

- The Conjugal Room

- Bar Den Haag

- Jack

- Home

-

- Acknowledgements

-

- About the Author

- By the Same Author

- Copyright

PART ONE

Cloonoila

The dirt of his travels, Gilgamesh washed from his hair, all the soiled garments he cast them off, clean new clothes he put on, about him now wrapped, clinging to him was a cloak with a fringe, his sparkling sash fastened to it.

The town takes its name from the river. The current, swift and dangerous, surges with a manic glee, chunks of wood and logs of ice borne along in its trail. In the small sidings where water is trapped, stones, blue, black and purple, shine up out of the river bed, perfectly smoothed and rounded and it is as though seeing a clutch of good-sized eggs in a bucket of water. The noise is deafening.

From the slenderest twigs of the overhanging trees in the Folk Park, the melting ice drips, with the soft, susurrus sound and the hooped metal sculpture, an eyesore to many locals, is improved by a straggling necklace of icicles, bluish in that frosted night. Had he ventured in further, the stranger would have seen the flags of several countries, an indication of how cosmopolitan the place has become and in a bow to nostalgia there is old farm machinery, a combine harvester, a mill wheel and a replica of an Irish cottage, when the peasants lived in hovels and ate nettles to survive.

He stays by the water’s edge, apparently mesmerised by it.

Bearded and in a long dark coat and white gloves, he stands on the narrow bridge, looks down at the roaring current, then

looks around, seemingly a little lost, his presence the single curiosity in the monotony of a winter evening in a freezing backwater that passes for a town and is named Cloonoila.

Long afterwards there would be those who reported strange occurrences on that same winter evening; dogs barking crazily, as if there was thunder, and the sound of the nightingale, whose song and warblings were never heard so far west. The child of a gipsy family, who lived in a caravan by the sea, swore she saw the Pooka Man coming through the window at her, pointing a hatchet.

*

Dara, a young man, the hair spiked and plastered with gel, beams when he hears the tentative lift of the door latch and thinks

A customer at last.

With the fecking drink-driving laws, business is dire, married men and bachelors up the country, parched for a couple of pints, but too afraid to risk it, with guards watching their every sip, squeezing the simple joys out of life.

‘Evening sir,’ he says, as he opens the door, sticks his head out, remarks on the shocking weather and then both men, in some initiation of camaraderie, stand and fill their lungs manfully.

Dara felt that he should genuflect when he looked more carefully at the figure, like a Holy man with a white beard and white hair, in a long black coat. He wore white gloves, which he removed slowly, finger by finger, and looked around uneasily, as if he was being watched. He was invited to sit on the good leather armchair by the fire, and Dara threw a pile of briquettes on and a pinch of sugar, to build up a blaze. It was the least he could do for a stranger. He had come to enquire about lodgings

and Dara said he would put the ‘thinking cap’ on. He proceeds to make a hot whiskey with cloves and honey and for background music the Pogues, at their wildest best. Then he lights a few aul candle stubs for ‘atmosphere’. The stranger declines the whiskey and wonders if he might have a brandy instead, which he swirls round and round in the big snifter, drinks and says not a word. A blatherer by nature, Dara unfolds his personal history, just to keep the ball rolling – ‘My mother a pure saint, my father big into youth clubs but very against drugs and alcohol … my little niece my pride and joy, just started school, has a new friend called Jennifer … I work two bars, here at TJ’s and the Castle at weekends … footballers come to the Castle, absolute gentlemen … I got my photo taken with one, read Pele’s autobiography, powerful stuff … I’ll be going to England to Wembley later on for a friendly with England … we’ve booked our flights, six of us, the accommodation in a hostel, bound to be a gas. I go to the gym, do a bit of the cardio and the plank, love my job … my motto is “Fail to prepare … prepare to fail” … Never drink on the job, but I like a good pint of Guinness when I’m out with the lads, love the football, like the fillums too … saw a great fillum with Christian Bale, oh he’s the Dark Knight an’ all, but I wouldn’t be into horror, no way.’

The visitor has roused somewhat and is looking around, apparently intrigued by the bric-a-brac in nooks and crannies, stuff that Mona the owner has gathered over the years – porter and beer bottles, cigarette and cigar cartons with ornamental lettering, a ceramic baby barrel with a gold tap and the name of the sherry region in Spain it came from, and in commemoration of a sad day, a carved wooden sign that reads ‘Danger: Deep Slurry’. That memento, Dara explained, was because a farmer in Killamuck

fell into his slurry pit one dark evening, his two sons went in after to save him and then their dog Che, all drowned.

‘Terrible sad, terrible altogether,’ he says.

He is at his wits’ end, scraping the head with a pencil, and jotting down the names of the various B & Bs, regretting that most of them are shut for the season. He tried Diarmuid, then Grainne, but no answer, and at three other joints he gets a machine, bluntly telling callers that no message must be left. Then he remembered Fifi, who was a bit of a card from her time in Australia, but she was not home, probably, as he said, at some meditation or chanting gig, a New Age junkie into prana and karma and that sort of thing. His last chance is the Country House Hotel, even though he knew they were shut and that husband and wife were due to leave on a trekking holiday in India. He got Iseult, the wife. ‘No way. No way.’ But with a bit of soft-soaping she relents, one night, one night only. He knew her. He delivered things there, wine and fresh fish including lobster from the quayside. Their avenue was miles long, twisting and turning, shaded with massive old trees, a deer park on one side and their own bit of river, sister to the town river, a humped bridge and then more avenue, right up to the front lawn, where peacocks strutted and did their business. Once, when he stepped out of the van, he happened to catch this great sight, a peacock opening his tail out, like a concertina, the green and the blue with the richness of stained glass, an absolute pageant. Some visitors, it seems, complained about the cries of the peacocks at night, said it had the weirdness of an infant in distress, but then, as he added, people will get funny notions into the head.

A youngster came in, to gawk at the strange figure in the dark glasses and went out roaring with laughter. Then one of the

Muggivan sisters came and tried to engage him in conversation but he was lost in his own world, thinking his own thoughts and muttering to himself, in another tongue. After she left he became more relaxed, let his coat slide off his shoulders and said he had been travelling for many days, but did not say where he had travelled from. Dara poured a second drink, more liberal with the measure this time and said they could put his name on the slate, as hopefully he would be coming in and out.

Other books

Red Baker by Ward, Robert

The Sword and The Prophet (A Syren Novel) by LaRae, Missy

Court Out by Elle Wynne

Rogue Belador: Belador book 7 by Dianna Love

Daric's Mate by J. S. Scott

The Thing Around Your Neck by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Unknown by Shante Harris

Ralph Compton Comanche Trail by Carlton Stowers