The Whites and the Blues (35 page)

Read The Whites and the Blues Online

Authors: 1802-1870 Alexandre Dumas

Tags: #Napoleon I, Emperor of the French, 1769-1821, #France -- History Revolution, 1789-1799 Fiction

It was long before silence could be restored, but order came at last. Boissy d'Anglas made a sign that he wished to speak. He was the very man to reply to such a speaker. The overbearing arrogance of the one was met by the dis dainful pride of the other. The monarchical aristocrat had spoken, and the liberal aristocrat was about to reply to him. Although there was a frown upon the president's brow, and his eyes were dark and menacing, his voice was calm.

4 'You have listened to the orator who has just spoken, 77 lie said. '' May you judge of the strength of the Convention by its patience. If any man had dared a few months ago to use here the language which the president of the Section Le Peletier has employed, his rebellious utterances would not

have been heard to an end. The orator's arrest would have been immediately decreed, and his head would have fallen upon the scaffold the following day. And why ? Because in days of carnage we are in doubt about everything, and we therefore destroy everything that may threaten our rights, that we may doubt no more. In the days of peace we pursue a different course, because we are no longer doubtful about our rights, and because, though at tacked by the Sections, we have behind us the whole of France and our invincible armies. We have listened to you without impatience, and we can therefore reply to you without anger. Go back to those who sent you; tell them that we give them three days in which to return to their allegiance, and that if they do not voluntarily obey the de crees within three days we shall compel them to do so.''

"And you," replied the young man, "if within three days you have not resigned your commission, if you have not withdrawn the decrees, and have not proclaimed the freedom of the elections, we declare to you that Paris will march against the Convention, and that it will feel the anger of the people."

"Very good," said Boissy d'Anglas; "it is now the 10th Vendemiaire—''

The young man did not allow him to finish.

"On the 13th Yenddmiaire," said he; "I give you my word that that will be another bloody date to add to your history!"

And rejoining his companions, he went out with them, threatening the entire assembly with a gesture. No one knew his name, for he had been appointed president of the Section Le Peletier through Lemaistre's instrumentality only three days before.

But every one said: "He is neither a man of the people uor a bourgeois; he must be an aristocrat."

CHAPTEK YI

THREE LEADERS

THAT same evening the Section Le Peletier convened in its committee rooms, and secured the co-opera tion of the Sections Butte-des-Moulins, Contrat-Social, Luxembourg, Theatre-Franchise, Kue Poissoniere, Brutus, and Temple. Then it filled the streets of Paris with bands of muscadins (the word is synonymous with incroyables, only with a wider meaning), who went about shouting, "Down with the Two-thirds Men!"

The Convention, on the other hand, mustered all the troops it could command at the camp of Sablons, about six thousand men, under General Menou, who in 1792 had commanded the second camp formed near Paris, and had been sent to the Vendee, where he had been defeated. These antecedents had secured him, on the 2d Prairial, the appointment of general of the interior, and had saved the Convention.

Some young men, shouting "Down with the Two-thirds Men!" had met a squad of Menou's soldiers, and refusing to disperse when ordered to do so, they had fired upon the soldiers, who had replied to their pistol-shots with gun shots, and blood had been shed.

In the meantime—that is to say, on the evening of the 10th Vend6miaire—the young president of the Section Le Peletier, which was then in session at the convent of the Daughters of Saint Thomas (which was situated on the spot where the Bourse now stands), gave up the chair to the vice-president, and, jumping into a carriage, was driven rapidly to a large house in the Kue Notre-Dame-des-Vic-toires, belonging to the Jesuits. All the windows of this house were closed, and not a ray of light escaped them.

The young man stopped the carriage at the gate and paid the driver; then, when the carriage had turned the

corner of the Kue du Puit-qui-parle, and the soun< the wheels had died away, he went a few steps further, and, making sure that the street was empty, knocked at the gate in a peculiar manner. The gate was opened so quickly that it was evident that some one was stationed behind it to attend to visitors.

"Moses," said the affiliated member who opened the gate.

"Manou," replied the new-comer.

The gate closed in answer to this response of the Hindoo to the Hebrew lawgiver, and the way being pointed out to the young president of the Section Le Peletier, he proceeded round the corner of the house. The windows overlooking the garden were closed as carefully as those which over looked the street. The front door was open, however, though a guard stood before it. This time it was the new-comer who said: "Moses!"

And the other replied, "Manou!"

Thereupon the door-keeper drew back to allow the young president to pass; and he, encountering no further obstacle, went straight to a third door, which admitted him to a room where he found the persons whom he was seeking. They were the presidents of the Sections Butte-des-Moulins, Contrat-Social, Luxembourg, Eue Poissoni&re, Brutus and Temple, who had come to announce that they were ready to follow the Mother Section, and to join in the rebellion.

The new-comer had hardly opened the door when he was greeted by a man about forty-five years of age, wearing a general's uniform. This was citizen Auguste Danican, who had just been appointed general-in-chief of the Sections. He had served in the Vende'e against the Vendeans, but, sus pected of connivance with Georges Cadoudal, he had been recalled, had escaped the guillotine by a miracle only, thanks to the 9th Thermidor, and had subsequently taken his place in the ranks of the counter-revolution.

The royalist Sections were at first strongly inclined to nominate the young president of the Section Le Peletier, who was highly recommended by the royalist agency,

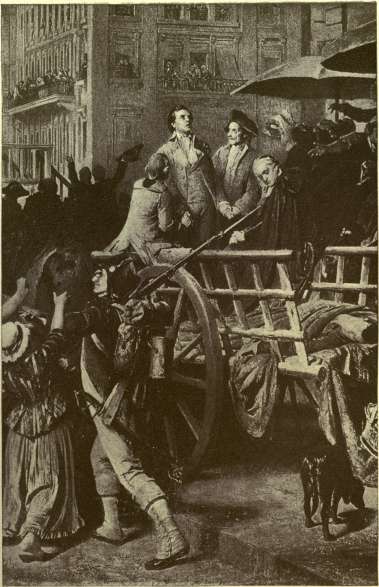

His companions in the cart were MM. de Montalembert, De Crequy, De Montmorency, De Loiserolles.

The Whites and the Blues, I —p. 244

through Lemaistre, and who had come from BesanQon only three days earlier. But the latter, learning that overtures had already been made to Danican, and that, if he were deprived of the command, the Sections would prob ably feel his enmity, declared that he would be satisfied with second or even third place, always providing that he should have an equal opportunity to take as active a part as possible in the inevitable battle.

Danican left a man of low stature with a twisted mouth and sinister expression to speak to the visitor. This was Freron. Fr£ron, repudiated by the Mountain, who aban doned him to the sharp stings of Mo'ise Bayle; Fre*ron, once a bigoted Eepublican, but who had in turn been re pudiated with disgust by the Girondins, who abandoned him to the withering curses of Isnard; Fre'ron, who, stripped of his false patriotism, though covered with the leprosy of crime, and feeling the need of sheltering himself behind the banner of some party, had joined the royalist faction which, like all parties who are on the losing side, was not too par ticular as to whom it admitted within its ranks.

We Frenchmen have passed through many revolutions, but not one of us can explain certain antipathies, which, in times of trouble, seem to attach to some political personages, and it appears equally difficult to attempt to explain certain illogical alliances. Freron was nothing, and had in no way distinguished himself. He had neither mind, character, nor political distinction. As a journalist he was a mere hack, selling to the first comer what was left of his father's repu tation and honor. Sent to the provinces as a representative of the people, he returned from Marseilles and Toulon, cov ered with royalist blood.

Explain it who can.

Freron now found himself at the head of a powerful party in which youth, energy, and vengeance were con spicuous, a party which burned with the passions of the times—passions which,-since the law was in abeyance, led

to everything except public confidence.

Vol. 24—1

THE WHITES AND THE BLUES

Fr£ron had just been relating with much emphasis the exploits of the young men who had come to open rupture with Menou's soldiers.

The young president, on the contrary, reported with the utmost simplicity the occurrences at the Convention, adding that retreat had now become an impossibility. War had been declared between the representatives and the members of the Sections; victory would unquestionably remain with those who marched first to the attack.

But however pressing the matter, Danican declared that nothing could be done until Lemaistre had returned to the session with the person who was with him. He had scarcely finished speaking, however, when the chief of the royalist agencies re-entered the room, followed by a man about twenty-five, with a frank open face, curly blond hair which almost hid his forehead, prominent blue eyes, a short neck, broad chest, and limbs that would have be come a Hercules. He wore the costume of the rich peasant of the Morbihan, save that he had added to it a gold braid about an inch wide, that bordered the collar and buttonholes of his coat, as well as the brim of his hat.

As the young leader advanced to meet him, the Chouan held out his hand. It was evident that the two conspirators knew they were to meet, and though unacquainted with each other, their recognition had been mutual.

CHAPTEK VII

GENERAL ROUNDHEAD AND THE CHIEF OF THE COMPANIONS OF JEHU

LEMAISTKE introduced them. "General Bound-head," said he, designating the Chouan; "Citizen Morgan, leader of the Companions of Jehu," bow ing to the president of the Section Le Peletier. The two young men shook hands.

"Although Fate determined that our birthplaces should be at the two extremities of France," said Morgan, "one conviction unites us. Although we are of the same age, you, general, have already won renown, while I am un known, or known only through the misfortunes of my house. It is to those misfortunes and my desire to avenge them that I owe the recommendation of the com mittee of the Jura, and the position which the Section Le Peletier has given me in making me its president on Mon sieur Lemaistre's introduction."

"M. le Comte," said the royalist, bowing, "I have not the honor like you to belong to the nobility of France. I am simply a child of the stubble and the plow. When men are called, as we are, to nsk their heads on the scaffold, it is well that they should know each other. One does not care to die in the company of those with whom they would not associate in life."

"Do all the children of the stubble and the plow express themselves as well as you do, general, in your country ? If so, you do not need to regret that you have been born with out the pale of that nobility to which I by accident belong.''

"I may say, count," replied the young general, "that my education has not been precisely that of the Breton peasant. I was the eldest of ten children, and was sent to the college at Yannes, where I received a good education."

"And I have heard," added the man whom the Chouan called count, "that it was early predicted that you were destined to great things."

" I do not know that I ought to boast of that prediction, although it has already been fulfilled in part. My mother was sitting in front of our house, holding me in her arms, when a beggar passed, and stopping, leaned upon his stick to look at us. My mother, as was her custom, cut a piece of bread for him and gave him a penny. The beggar shook his head. Then touching my forehead with the tip of his bony finger, he said: 'There is a child who will bring about great changes in his family, and who will cause much trouble

to the state.' Then, looking at me sadly, he added: 'He will die young, but he will have accomplished more than most old men,' and he continued on his way. Last year the prophecy was fulfilled as far as my family was concerned. I took part as you know in the insurrection of the Yend6e of'93 and'94."

"And gloriously," interrupted Morgan.

U I did my best. Last year, while I was organizing the Morbihan, the soldiers and gendarmes surrounded our house. Father, mother, uncle and children were all carried off to prison at Brest. It was then that the prediction which had been made concerning me when I was a child recurred to my mother's mind. The poor woman reproached me with tears for being the cause of the misfortunes of the family. I tried to console her and to strengthen her by telling her that she was suffering for God and her king. But women do not appreciate the value of those two words. My mother continued to weep and died in prison in giving birth to another child. A month later my uncle died in the same prison. On his deathbed he gave me the name of one of his friends to whom he had loaned nine thousand francs; this friend had promised to return the sum whenever he should ask for it. When my uncle died my only thought was to escape from prison, obtain the money, and apply it to the cause of the insurrection. I succeeded. My uncle's friend lived at Eennes. I went to his house, only to learn that he had gone to Paris. I followed him here and obtained his address. I have just seen him, and faithful and loyal Bre ton that he is, he has returned me the money in gold, just as he borrowed it. I have it here in my belt," continued the young man, putting his hand to his hip. '' Nine thou sand francs in gold are worth two hundred thousand to-day. Do you throw Paris in confusion, and in a fortnight all the Morbihan will be in flames!"