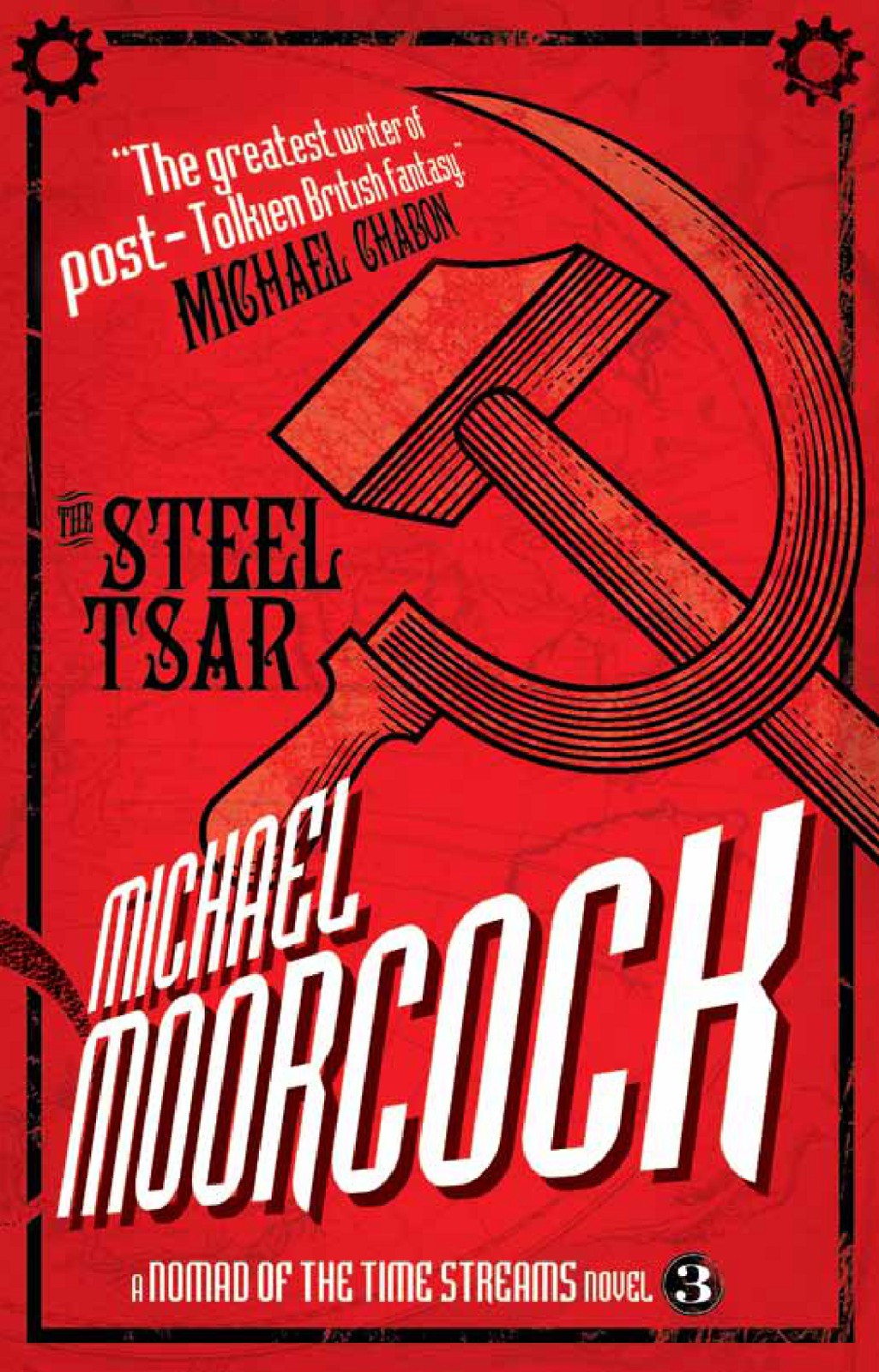

The Steel Tsar

Authors: Michael Moorcock

Tags: #Fiction, #Science Fiction, #Steampunk Fiction, #General

NOMAD OF THE TIME STREAMS

NOVEL

THE THIRD ADVENTURE

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

The Warlord of the Air

The Land Leviathan

NOMAD OF THE TIME STREAMS

NOVEL

THE THIRD ADVENTURE

THIRD VOLUME IN THE OSWALD BASTABLE TRILOGY

TITAN

BOOKS

The Steel Tsar

Print edition ISBN: 9781781161470

E-book edition ISBN: 9781781161500

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: August 2013

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Michael Moorcock asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Copyright © 1981, 2013 by Michael Moorcock.

Foreword copyright © 2013 by Kim Newman.

Edited by John Davey.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers.

Please email us at

[email protected]

or write to us at Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website:

www.titanbooks.com

For all who died at Babi Yar and for Anatoly Kuznetsov, who died speaking the truth and whose work was stolen by a liar

Book One: An English Airshipman’s Adventures in the Great War of 1941

Chapter One: The Manner of My Dying

Chapter Two: The Destruction of Singapore

Chapter Five: The Price of Fishing Boats

Chapter Six: The Mysterious Dempsey

Chapter Nine: Hopes of Salvation

Book Two: “Neither Master Nor Slave!”

Chapter One: The Camp on Rishiri

Chapter Three: Cossack Revolutionists

Chapter Five: A Question of Attitudes

Chapter Seven: A Mechanical Man

F

irst published between 1971 and 1981, Michael Moorcock’s

The Warlord of the Air

(or is it

The War Lord of the Air

?— editions vary),

The Land Leviathan

and

The Steel Tsar

—three books known collectively as “The Oswald Bastable Trilogy” or “A Nomad of the Time Streams”—look backwards, forwards and sideways at the same time.

In 1969, there were people going around seriously saying that science fiction would die as a genre after the moon landing. The future was here, so we didn’t need to think about it any more. Certainly, the genre had been around long enough by then for its earlier examples to seem comically outdated—all those books and stories where there’s a breathable atmosphere on the moon, or astro-navigators fiddle with slide rules on their faster-than-light spaceships. Still, there were people who saw the beauty and the terror and (most importantly) the continued relevance of the futures which didn’t happen.

In Moorcock’s novels, army officer Oswald Bastable—the name comes from a series of books by E. Nesbit, author of

Five Children and It

—comes unstuck in time from his own era (1903) and tours three overlapping, yet different, imagined versions of the twentieth century... where the British Empire persists into the 1970s, technological advances lead to a war that leaves the world in ruins in the early 1900s and a Russian revolution did not lead to a Soviet state. Constant in all these fractured mirrors of our own history are airships, stately hold-overs from the exciting books of Jules Verne (

The Clipper of the Clouds)

and George Griffith

(The Angel of the Revolution),

and the atomic bomb (which arrived in fiction in 1914 in H.G. Wells’

The World Set Free).

The point is not, as in some meticulously constructed and argued alternative histories, to imagine how things might have been, but to confront the way things really were, as our collective urges for incompatible utopias brought about horrors beyond imagining. Though not averse to blaming individuals, these books are strong on collective responsibility: there are versions here of Joseph Stalin, Ronald Reagan, Enoch Powell and Harold Wilson, as sad little men whose small-minded blind spots, ambitions and cruelties bring about personal and global disasters. But no one is let off the hook, and we’re all to blame.

The voice of these novels is a perfect match for the Victorian and Edwardian authors evoked over and over in them... not just Wells, Nesbit and Griffith, but Rider Haggard, Conan Doyle, Rudyard Kipling

(With the Night Mail),

Saki

(When William Came

—a novel Moorcock brought back into print in the anthology

England Invaded

), George Tomkyns Chesney (

The Battle of Dorking

) and many other scientific romancers of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Moorcock can embrace, with love, the idealism and imagination expressed in these writers’ works, though as many were catastrophists as utopians, but recognizes that they share in the collective responsibility for the way the world really turned out. A key influence on the steampunk movement in contemporary fantasy, these books are spikier, more clear-sighted and complicated than most superficially similar visions of technological Victoriana.

These books are Griffith-like yarns—full of scrapes, adventures, exotica, jokes, plot reversals and charm—but they’re at heart serious, sobering visions. I am delighted they are available again, and so will you be.

KIM NEWMAN

London, 2012

AN ENGLISH AIRSHIPMAN’S ADVENTURES IN THE GREAT WAR OF 1941

CHAPTER ONE

The Manner of My Dying

I

t was, I think, my fifth day at sea when the revelation came. Just as at some stage of his existence a man can reach a particular decision about how to lead his life, so can he come to a similar decision about how to encounter death. He can face the grim simple truth of his dying, or he can prefer to lose himself in some pleasant fantasy, some dream of heaven or of salvation, and so face his end almost with pleasure.

On my sixth day at sea it was obvious that I was to die and it was then that I chose to accept the illusion rather than the reality.

I had lain all morning at the bottom of the dugout. My face was pressed against wet, steaming wood. The tropical sun throbbed down on the back of my unprotected head and blistered my withered flesh. The slow drumming of my heart filled my ears and counterpointed the occasional slap of a wave against the side of the boat.

All I could think was that I had been spared one kind of death in order to die alone out here on the ocean. And I was grateful for that. It was much better than the death I had left behind.

Then I heard the cry of the seabird and I smiled a little to myself. I knew that the illusion was beginning. There was no possibility that I was in sight of land and therefore I could not really have heard a bird. I had had many similar auditory hallucinations in recent days.

I began to sink into what I knew must be my final coma. But the cry grew more insistent. I rolled over and blinked in the white glare of the sun. I felt the boat rock crazily with the movement of my thin body. Painfully I raised my head and peered through a shifting haze of silver and blue and saw my latest vision. It was a very fine one: more prosaic than some, but more detailed, too.

I had conjured up an island. An island rising at least a thousand feet out of the water, about ten miles long and four miles wide: a monstrous pile of volcanic basalt, limestone and coral, with deep green patches of foliage on its flanks.

I sank back into the dugout, squeezing my eyes shut and congratulating myself on the power of my own imagination. The hallucinations improved as any hopes of surviving vanished. I knew it was time to give myself up to madness, to pretend that the island was real and so die a pathetic rather than a dignified death.

I chuckled. The sound was a dry, death rattle.

Again the seabird screamed.

Why rot slowly and painfully for perhaps another thirty hours when I could die now in a comforting dream of having been saved at the last moment?

With the remains of my strength I crawled to the stern and grasped the starting cord of the outboard. Weakly I jerked at it. Nothing happened. Doggedly, I tried again. And again. And all the while I kept my eyes on the island, waiting to see if it would shimmer and disappear before I could make use of it.

I had seen so many visions in the past few days. I had seen milk-white angels with crystal cups of pure water drifting just out of my reach. I had seen blood-red devils with fiery pitch-forks piercing my skin. I had seen enemy airships which popped like bubbles just as they were about to release their bombs on me. I had seen orange-sailed schooners as tall as the Empire State Building. I had seen schools of tiny black whales. I had seen rose-coloured coral atolls on which lounged beautiful young women whose faces turned into the faces of Japanese soldiers as I came closer and who then slid beneath the waves where I was sure they were trying to capsize my boat. But this mirage retained its clarity no matter how hard I stared and it was so much more detailed than the others.

The engine fired after the tenth attempt to start it. There was hardly any fuel left. The screw squealed, rasped and began to turn. The water foamed. The boat moved reluctantly across a flat sea of burnished steel, beneath a swollen and throbbing disc of fire which was the sun, my enemy.

I straightened up, squatting like a desiccated old toad on the floor of the boat, whimpering as I gripped the tiller, for its touch sent shards of fire through my hand and into my body.