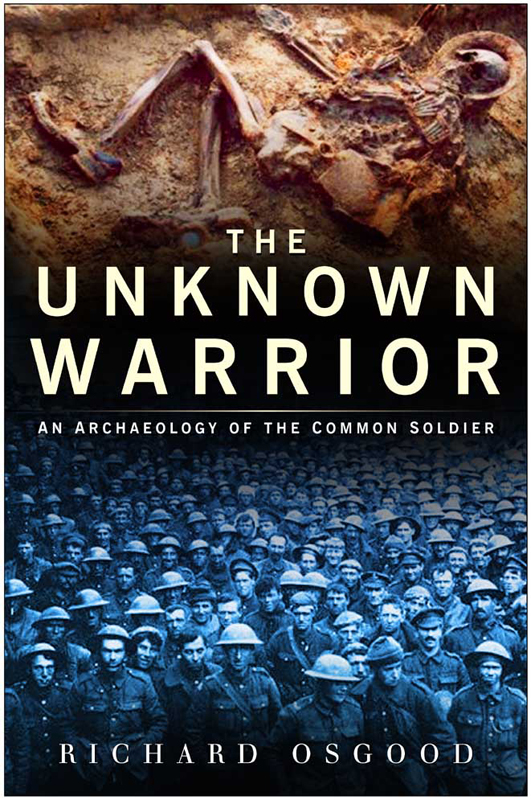

The Unknown Warrior

Read The Unknown Warrior Online

Authors: Richard Osgood

THE

UNKNOWN

WARRIOR

THE

UNKNOWN

WARRIOR

A

N

A

RCHAEOLOGY OF THE

C

OMMON

S

OLDIER

RICHARD OSGOOD

First published in the United Kingdom in 2005 by

Sutton Publishing Limited

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Richard Osgood, 2005, 2013

The right of Richard Osgood to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9546 0

Original typesetting by The History Press

For Katherine Freya

Contents

1.   The Dawning of the Arms Race: Bronze Age Warriors

2.   Under the Eagle's Wings: In the Service of the Roman Legions

3.   Heroes of the Chronicles and Sagas: Anglo-Saxon and Viking Warriors

4.   Chivalry's Price: Footsoldiers of the Middle Ages

5.   The Flash of Powder: War in the Tudor and Stuart Period

6.   The Revolution of Industry: Soldiers of the Nineteenth Century

7.   Marching to Hell: The Poor Bloody Infantry in the First World War

Acknowledgements

First, I acknowledge the great help that has been given to me by my friend and archaeological colleague Martin Brown, during the preparation of this work. Secondly, I would like to extend my thanks to the following individuals and groups for their assistance:

Bronze Age Britain

Professor Mike Parker Pearson, for discussions on this topic over the years; Gail Boyle, of Bristol Museum, for helping with Tormarton; Ruth Pelling, for archaeobotanical information; Professor John Evans, for his kind donation of the Stonehenge images.

Early Roman Period

Dr Eberhard Sauer, for information on his work at Alchester; Dr Simon James, for advice on matters pertaining to Dura Europos; Dr Susanne Wilbers-Rost and Kalkriese Museum, for information on the site of the demise of the Varus Legions; Professor Mark Robinson, for information on diet; Oxford Archaeology and English Heritage for Carlisle artefacts; Dr Martin Henig on matters religious.

Anglo-Saxon and Viking Era

Dr Chris Knüsel and the Late Sonia Chadwick-Hawkes, for details of the Eccles skeletons; Dr Paul Budd, for information on the scientific studies of the Riccall burials; Professor Martin Biddle, for help with Repton; Dr Andrew Reynolds for matters Saxon.

Medieval Period

Dr Chris Knüsel, for information on the work at Towton; all those connected with Visby, including Professor Ebba During and Marie Flemström; Siv Falk and Annica Ewing of the Statens Historiska Museum; the Royal College of Physicians, Edinburgh, for providing details of Soutra; Martin Brown and Lucy Sibun, for discussing the Lewes burials; Chris Daniell, for work on the Fishergate bodies.

Tudor and Stuart Ages

Dave Allen and Alan Turton, for discussing the Basing House skull with me many moons ago; Glenn Foard, for comments made at a conference at the National Army Museum.

Nineteenth Century

Tony Pollard, Ian Knight and Adrian Greaves, for their information on archaeological work in connection with the Zulu War; Phil Freeman, who gave me important information about his work in the Crimea; Professors Rimantas Jankauskas (burials of the Grand Armeé, Vilnius) and Barry Cunliffe (prisoner-of-war camp, Portchester), who provided assistance with matters Napoleonic; Mario Espinola, whose work on Centreville was vital to my understanding of aspects of the American Civil War â to him I also extend my thanks in pointing out other resources, both of excavation information and relevant literature.

First World War

Information on the archaeology of the First World War was obtained from several sources, including discussions at conferences, emails and telephone calls. Alastair Fraser and Andy Robertshaw provided details about their excavations at Auchonvillers; Alain Jacques provided similar knowledge about Arras. Aurel Sercu afforded me information about The Diggers work in Flanders, assisted by Paul Reed and John Hayes Fisher; Rob Janaway discussed the findings of Belgian material with me. Evidence for practice trenches was provided by Paul Sidebottom and Peter Beckett; Bob Moore helped with evidence about prisoners of war. Martin Brown was always generous in keeping me abreast of his exciting work at Serre and of practice trenches on Defence Estates that lay outside Salisbury Plain. Richard Petty was kind enough to let me photograph his family's collection of trench art. Using the Internet, I was able to ask many people questions about First World War archaeology â Nils Fabiansson and members of the Great War Forum were especially helpful.

Introduction

The principal results we obtain from the whole of these considerations are:

1. That infantry is the chief arm, to which the other two are subordinate.

2. That by the exercise of great skill and energy in command, the want of the two subordinate arms may in some measure be compensated for, provided we are much stronger in infantry; and the better the infantry the easier this may be done.

(Von Clausewitz,

On War

)

As I write this, apart from the obvious bustle of the office â of colleagues, computers, printers and photocopiers â the only sounds I can hear are the sounds from the open window: the shrill warbling of a skylark. That is apart from the occasional whistle as a shell passes overhead and thuds into the earth some miles away with the resulting percussion rattling the same window. To my untuned ear I could not tell you whether this is the twenty-first-century equivalent of a âJack Johnson', a âMinnie' or a âWhizz-bang' and I marvel at the infantrymen who, within a short space of time, were able to distinguish such variances; an ability that could be life-saving.

I have just returned from a site visit to a set of Australian practice trenches from the First World War. Though these were backfilled in the 1920s, elements of the material that filled them are still being brought to the surface by burrowing animals. Hence, pieces of rusting metal, Bovril jars, Camp coffee bottles and an Anzora bottle now adorn my desk, much to the bewilderment of several workmates. Yet this is the fabric of humanity that fascinates me â the residue of life (anthropology if you like); for, where books will inform the reader of the outcome of a selected battle, the history of particular regiments or the lives of great generals, little time is dedicated to the average fighting soldier â the âPoor Bloody Infantry'.

This, I believe, is where archaeology is invaluable, for it can inform us of the lives of those who did the fighting. How much has ever been written on what was eaten by men when training, or on the replication of conditions they could have expected to experience? Archaeology informs us of the lives of these men and women involved in combat, with the main bias being survival conditions. It can tell us about the actual weapons that were used in fighting, rather than those simply depicted in paintings or in an ideal inventory of weaponry of the age. It can tell us of the diseases suffered by these people, their living conditions and the assistance they could hope for when wounded. Survey and excavation can show us how footsoldiers passed their time when not fighting and can perhaps reinforce our impression that, even centuries ago, their acts were not so very different from those of troops today. Soldiers throughout history have, for example, left a trace of their presence; they have carved their names and messages into buildings and monuments. Perhaps the very fact that their lives are lived closer to death than many other people's renders a desire to leave a physical trace that much stronger. Even today, soldiers will add their names, or those of their regiments, to the walls of barracks and training facilities.

Traces of warfare in the archaeological record seem to have become a much-examined subject in recent years â the topic of many conferences, journal titles, monographs, television programmes and archaeological research designs. There is a profusion of Internet sites dedicated to this sphere alone. As a consequence, I have been fortunate to draw upon the splendid work of a wide range of people when assembling this book.

I have decided to concentrate on the fighting soldiers â the infantrymen â as they are the ones who are vital in any combat to take land and hold it. Wherever possible I have avoided recourse to historical references as it is the archaeology I wish to examine â after all, who is to say that written histories are unbiased? At least the archaeological resource favours no side or individual, and I hope that the work will illuminate the rich resource we can turn to when we question events that occurred many years ago. The only writings I want to dwell on in this study will be either the graffiti of the troops or the physical writings (and writing equipment) present in archaeological deposits. The amount of information available will vary from chapter to chapter â after all, there is nothing by way of epigraphic source for the Bronze Age, whereas there is much for the First World War â and thus the chapters differ in length.

I would also not be so foolish to claim that this work is all-encompassing. For each chapter I have tried to provide a flavour of the evidence available within the time period rather than to collate everything relevant to each epoch. Furthermore, one will also be aware that most of the chapters have a distinctly âBritish-Isles-centric' feel to them, or at least to wars in which Britain had an interest. This seems sensible to me, as it would at least give an idea of evolution of tactic and of equipment within a country that has been engaged in much warfare from prehistoric times to the present day. That being said, we are still able to draw in examples from North America, Western and Northern Europe, South Africa and Syria, so, hopefully, the work does not prove to be too insular.

In the following chapters, we will examine the Bronze Age warrior in Britain, the legionary of the early Roman Empire, the Anglo-Saxon warrior and his Viking counterpart, the regular and peasant forces of the Medieval era, footsoldiers of the Tudor and Civil War period of Britain, those who fought in the Napoleonic and Victorian eras and the American Civil War and, finally, the infantrymen of the First World War.

With this generous and noble spirit of union in a line of veteran troops, covered with scars and thoroughly inured to war, we must not compare the self-esteem and vanity of a standing army, held together merely by the glue of service-regulations and a drill book; a certain plodding earnestness and strict discipline may keep up military virtue for a long time, but can never create it; these things therefore have a certain value, but must not be overrated. (Von Clausewitz, 1997: 157)

New work seems constantly to be emerging on the subject of the archaeology of war and hopefully this will enable us better to understand the gamut of emotions felt by infanteers from training to combat. We all feel we know about various wars as a result, perhaps, of poetry, writings, paintings and even films. Archaeology, far from being a mere handmaiden of history, can actually add new tones to the canvas or even redesign the painting, providing aspects of detail unavailable to the historian. In discussing this subject with friends and colleagues, I have had many stimulating debates with serving soldiers, archaeologists and historians and feel that we are able to say far more through archaeology than simply âsoldiers smoked and drank' (something suggested to me by a historian friend)