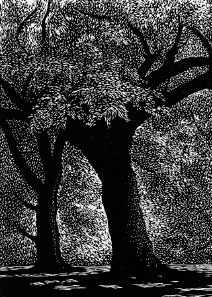

The Tree In Changing Light

Read The Tree In Changing Light Online

Authors: Roger McDonald

Also by Roger McDonald

FICTION

1915

Slipstream

Rough Wallaby

Water Man

The Slap

Mr Darwin's Shooter

The Ballad of Desmond Kale

NON-FICTION:

Shearer's Motel

AS EDITOR:

Gone Bush

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted by any person or entity, including internet search engines or retailers, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including printing, photocopying (except under the statutory exceptions provisions of the Australian

Copyright Act 1968

), recording, scanning or by any information storage and retrieval system without the prior written permission of Random House Australia. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

The Tree in Changing Light

9781742754680

The writing of this work was assisted by a fellowship from the Australia Council, the Federal Government's arts funding and advisory board.

A Vintage Book

Published by Random House Australia Pty Ltd

Level 3, 100 Pacific Highway, North Sydney, NSW 2060

http://www.randomhouse.com.au

Sydney New York Toronto

London Auckland Johannesburg

First published in Australia by Knopf, an imprint of Random House Australia, 2001.

This Vintage edition first published 2002.

Copyright © Roger McDonald 2001.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication Entry

McDonald, Roger, 1941-.

The tree in changing light.

ISBN 1 74051 181 6 (pbk).

ISBN 978 1 74051 181 0 (pbk).

Trees â History. 2. Forests and forestry â History. 3.

Trees â Social aspects. 4. Plants and civilization. I.

Atkins, Rosalind. II. Title.

333.75

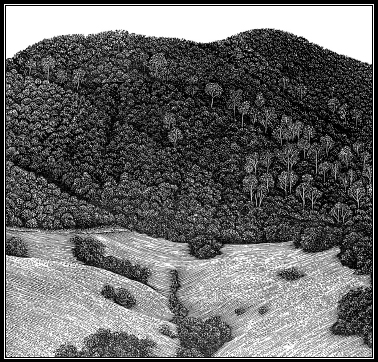

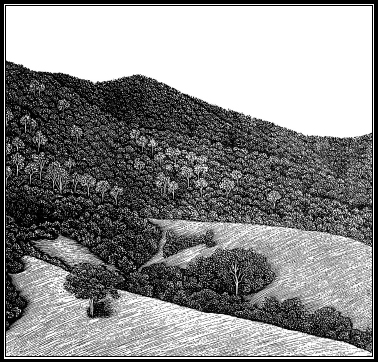

Wood engravings © Rosalind Atkins.

Cover design by Peter Long.

Internal design by Greendot Design.

âNo genuine book has a first page. Like the rustling of a forest, it is begotten God knows where, and it grows and it rolls, arousing the dense wilds of the forest until suddenly, in the very darkest, most stunned and panicked moment, it rolls to its end and begins to speak with all the treetops at once.'

âWhatever happened, there would remain the feeling

underneath, the shape of a tree where no tree was

before. It regathered itself and insisted on thickening

into life. The planter appeared, arms out like branches,

trunk measured against trunk, head moving

against the stars â¦'

I

T HAPPENED

best after good soaking rain in well-drained soil holding moisture to a useful depth. Behind the chugging tractor the ripper blade in a shining âJ' dragged along on the lumpy dirt. Movement started, the ripper lowered and bit, the metal shaft went into the ground barely breaking a seal. Slicing through parting clumps of grass it unfurled a polished banner of continuous earth. Bundles of grass roots were sectioned; worms divided. Forward of the point where the cut peeled open a swelling ran as if a subterranean animal were under there smoothly plummeting through the paddock and hurrying ahead to keep out of the way.

Planters followed with bundles of seedlings in plastic tubes and dropped them at intervals against the furrow. It happened quickly, what happened nextâthe transition from which comes momentous change (or may); a spade levering earth at an angle; the planter dropping to the knee, or to both knees in a quick unconscious plea for life backed by a dirty-fingernailed routine of plastic casing off, naked root-shaft palmed this way or that, then into the ground, a bit rough;

planting out was like that. Over. And on to the next one all morning, all afternoon, until a stitching of feathery-topped seedlings counted in hundreds, and then in thousands, embroidered the paddock and ran over the hill and into the dark.

What might come of this could only be guessed. Some time later a forest? Birdlife and the layering of ecology once cleared out? Or simple failure and starting over againâno further rain this season; massed insect attack; wandering stock trampling and feedingâthe dry stars overhead like so many wasted seeds.

Whatever happened, there would remain the feeling underneath, the shape of a tree where no tree was before. It re-gathered itself and insisted on thickening into life. The planter appeared, arms out like branches, trunk measured against trunk, head moving against the stars.

Â

Germination was a spark of light. Seed, fine as ground pepper, scattered and struck. Seedlings emerged through leaf matter glistening with dew.

Shoots slithered from the ground as delicately as fine hair. Two small leaves parted and bared themselves to light. The evolving architecture of the tree began. Angle of branch, buckled fold of bark, shaggy river of red sap. It was the seedling giving consideration to the elements, designing itself into the sky with tree after tree undulating along the ridge.

Â

âThe tree grew not by stretching elastically (like a leech) but step by step, by means of addition or superimposition.

Although the living shoot of any year lengthened until it reached its terminal bud, after that bud was formed its length was fixed. It was thenceforth one joint of the tree, like the joint of a pillar, on which other joints of marble were laid to elongate the pillar, but which would not itself stretch. A tree was thus truly edified, or built, like a house.'

Â

Leaves were solar collectors. They generated sugars that flowed through the inner bark and changed into the woody material of the branches, trunk, and roots. The slide of stored light (each year recorded in growth rings) was how the tree increased in sizeâwith an effect like a candle coating itself and growing fatter at the base.

From the bare gate a kilometre off a particular tree on the high sandy plateau resembled a child's transfer. Scattered across the slope were others of the same species. Some showed brittle, skeletonised limbs and gappy, insect-eaten foliage. Others seemed to have been drawn with a snapped pencil. The light showed through all of them. As I drove closer the one tree thickened and spread, showing itself immense in the winter light. The way it played back and forth with scale, now puny, now enormous, was a conversation we had every time I drove the last kilometre. When I left the car the trunk rose sleek as marble, cold and weighted to the touch. Checking it over by feel, smoothing the bark, impressed by its elephant-like presence, I stepped back seeing what sticks had fallen while I was away (upper wood with a habit of loosing itself and crashing). There was a matting of twigs underfoot, a rain of firewood fallen among corkscrewed

scrolls of bark and layered leaves. Out came a cardboard box and in moments enough kindling was gathered for the fire.

Inside the house the Warmray stove crackled with flame struck from the tree's stored light.

Â

At night outside, trees led the eye back to the stars. The scatter of stars and the pattern of branches joined. The farthest bud and the farthest beginnings of life connected.

On summer nights tree insects swarmed. I went outside batting scarab beetles from my face and wondering where the roar of wind came from.

Â

Moths on a windowpane held the shape of the tree behind them. The tree was a cut-out shadow against the stars. And the stars were a spiral of moths.

Â

Clouds settled in the tops of trees. The fretworked tips of leaves and moisture droplets combined. So it rained under the trees, but nowhere else, condensation forming a drip line. Boys climbed the trees with the aim of getting higher. In their hearts they raced the clouds, though a poem could have told them:

Too much rain

loosens trees.

In the hills giant oaks

fall upon their knees.

You can touch parts

you have no right toâ

places only birds

should fly to.