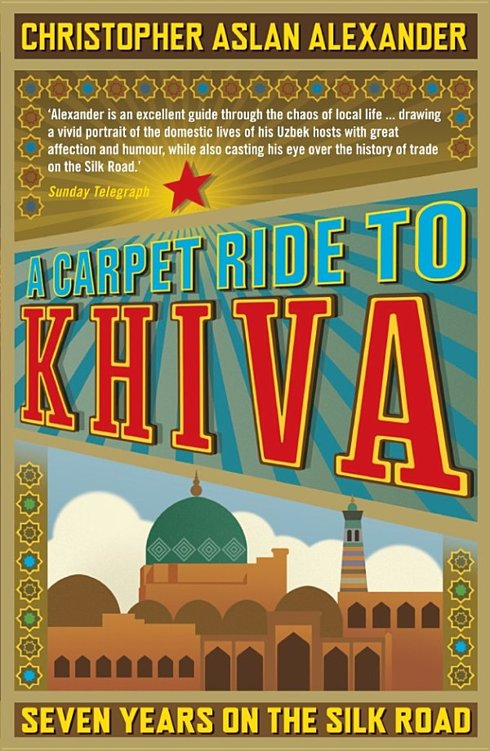

A Carpet Ride to Khiva: Seven Years on the Silk Road

Read A Carpet Ride to Khiva: Seven Years on the Silk Road Online

Authors: Christopher Aslan Alexander

Tags: #travel, #central asia, #embroidery, #carpet, #fair trade, #corruption, #dyeing, #iran, #islam

![]()

Previously published in the UK in 2010

by Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP

email:

[email protected]

This electronic edition published in the UK in 2011 by Icon Books Ltd

ISBN: 978-1-84831-271-5 (ePub format)

ISBN: 978-1-84831-272-2 (Adobe ebook format)

Printed edition (ISBN

978-184831-149-7)

sold in the UK, Europe, South Africa and Asia

by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House,

74–77 Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3DA

or their agents

Printed edition distributed in the UK, Europe, South Africa and Asia

by TBS Ltd, TBS Distribution Centre, Colchester Road,

Frating Green, Colchester CO7 7DW

Printed edition published

in the USA in 2010 by Totem Books

Inquiries to: Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP, UK

Printed edition distributed to the trade in the USA

by Consortium Book Sales and Distribution

The Keg House, 34 Thirteenth Avenue NE, Suite 101

Minneapolis, Minnesota 55413-1007

Printed edition published in Australia in 2010 by Allen

& Unwin Pty Ltd,

PO Box 8500, 83 Alexander Street,

Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Printed edition published in Canada by Penguin Books Canada,

90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700,

Toronto, Ontario M4P 2YE

Text copyright © 2010 Christopher Aslan Alexander

The author has asserted his moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any

means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset by Marie Doherty

Contents

Prologue: Tashkent transit lounge

Chapter 1: The walled city of Khiva

Chapter 2: A home by the harem

Chapter 4: From calligraphy to carpet

Chapter 5: Worms that changed the world

Chapter 9: A carpet called Shirin

Chapter 10: Navruz and new beginnings

Chapter 12: Signed with a pomegranate

About the author

Christopher Aslan Alexander

was born in Turkey (hence his middle name) and grew up there and in war-torn Beirut (as a boy, his understanding of a shell collection was more the weapon variety). He spent his teenage years in England before escaping for two years at sea. Chris studied media at Leicester and became the first white boy in the university gospel choir.

After a year working for the students’ union, Chris moved to land-locked Central Asia, volunteering with Operation Mercy, a Swedish NGO. While writing a guidebook about Khiva, he fell in love with this desert oasis – which boasts the most homogeneous example of Islamic architecture in the world – and stayed.

To my team-mates in Khiva, my Uzbek family, friends and colleagues. And especially to Madrim:

Katta minnatdorchilik bildirib, do’stligimiz abadiy bo’lishini tilab qolaman

Author’s note

I have used the terms ‘carpet’ and ‘rug’ interchangeably. Pedants will argue that one is larger than the other, but this distinction is rarely acknowledged in modern-day usage.

Most Uzbek words appear in the glossary and are generally pronounced phonetically. The exception is the ‘kh’ sound which is always pronounced the way Scots pronounce the ‘ch’ in the

word ‘loch’. I have written most Uzbek words phonetically, their pronunciation often different from the same word in Farsi or Turkish.

Technical terms from carpet-weaving and design can also be found in the glossary.

For the most part, I have used people’s real names except when to do so might endanger them. The views held in this book are my own and in no way reflect those of Operation

Mercy, UNESCO or the British Council.

Prologue

Tashkent transit lounge

I’d always imagined that if I wrote a book about the carpet workshop and my time in Khiva, it would be written, or least begun, in the workshop itself. I’d sit in my office – a cell in the Jacob Bai Hoja madrassah – and write about the beginnings: the transformation of a disused and derelict madrassah into a centre for natural dye-making,

silk carpet-weaving, and exploration into long-forgotten carpet designs. My laptop would be plugged into the rickety socket in my corner office cell next to the phone that rang incessantly, occasionally with carpet orders but usually with mothers passing on shopping lists to their daughters, or amorous young men unable to meet a young weaver in public but happy to court over the phone. I’d sit

there typing as the light filtered through the arched plaster latticework, forming hexagonal pools of light on the stone floor. Perhaps Madrim would sit next to me, magnifying glass in hand, bent over a copy of a 15th-century manuscript, examining a carpet illustrated within its pages, partially obscured by a Shah or courtesan.

I’d look around our small office that once accommodated students

of the Koran, now filled with a carved wooden table and chairs, beautifully constructed by my friend Zafar and his brothers; the wall niche that once held a Koran, now crammed with books and laminated carpet designs; the sleeping alcove, supported by thick ceiling beams, now storage for fans or electric heaters.

Sounds would filter through the small wooden door: the thumping of weavers’

combs on the weft threads that mark the completion of each new row of silk knots; the rhythmic pounding of oak gall being crushed in the large brass mortar by Jahongir, our chief dyer; the loud

thwack

of dried silk skeins beaten hard against the wall, removing the entangled remains of powdered madder root or pomegranate rind. Over this, the sound of an argument between loom-mates from one cell,

laughter from another, competing Uzbek, Russian and Turkish pop music, and the voice of Aksana giving a guided tour.

But this book will never be written in my office, or anywhere else in Khiva. Next to me, a bag full of gifts for the weavers and dyers who have become my family sits unopened. I am in the transit lounge in Tashkent. This is the furthest I can get, having been refused entry

into Uzbekistan. I feel rumpled and tired, and have spent the last few nights sleeping on newspaper. More than that, I feel a crushing sense of loss, a dull ache around my heart that sometimes shifts to a constriction in my chest. I’m not sure how long I will be stuck here for, what I’ve done wrong, or whether I will ever return to the desert oasis I now call home.

Tashkent, November 2005