The Traitor (19 page)

Authors: Sydney Horler

The Secret Writing

As the different members of the court-martial rose and went out by the door behind the President, Rosemary felt her temples throbbing. She realised she would have to abandon hope. There could be only one result of the trial, and that would be a verdict of “Guilty.”

She had been sustained until now, but the whispered words of her Chief, Sir Brian Fordinghame, as he sat down by her side, brought both fear and desolation.

“The experts say there is nothing on either,” Fordinghame stated, passing over the two sheets of lightish blue paper over which she had expended so much hope.

This was the end, then. Her intuitionâthat same intuition on which she had so prided herselfâhad been proved wrong; it had let her down badly.

***

The night before, disregarding the protests of both Dr. McColl and her father, she had got up from bed as soon as she was able and, dressing, had gone down to the library. There was a book there which she wanted to consult. During the few hours that remained before the court-martial proceedings restarted she would read up everything possible on the subject of spies and secret writing.

It was that night's intruder who had given her the idea. The man must have been after the package. There was nothing else in her room of any value, apart from a few jewels, and he had ignored those. No, he must have come for the package.

Why?

Becauseâthe answer, to her mind, was obviousâit was of vital importance to some person or group of personsâto a foreign country. Then, if it had this importance, it must also be of paramount value to the court-martial.

She had imagined she could see more or less clearly now what before had been so dark: Bobby must have been given this package

by mistake

. How this blunder had been committed she could not tell, of course, but, as she continued to throw on a few clothes, her heart seemed to stop beating when she realised how narrowly the papers had escaped total destruction.

On the night that Bobby had refused to give her his complete confidenceâwhen, for some unaccountable reason, he had lied to herâshe had been strongly tempted to throw the wretched package into the fire. Why not? The whole thing was a bluff. What possible value could there be in two perfectly blank sheets of paper?

Sir Brian Fordinghame would be able to decide, of course; but, before meeting her Chief at the office, she herself had wanted to master, as far as was possible, the fascinating subject of Secret Writing. For that was what these sheets contained, she had felt certainâ

secret writing

. That seemed the answer to the puzzle.

Locking herself in the library (she had still felt groggy, but had fought hard against the sense of nausea), she had gone to the shelf on which she remembered having seen the book, and had taken down a heavy volume, on the back of which was printed

The Arts and Crafts of Modern Espionage

. How Fordinghame would have smiled if he could have seen her! Everything between these two covers was known to him, she supposed.

Still, she hadn't minded about that; she had wanted to discover the possible secret for herself. The thumping of her father's hand on the door had been disregarded.

“Look here, Rosemary, Dr. McColl isn't at all pleased with youâneither am I,” she had heard her bewildered parent wail.

This was intolerable.

“Oh, do go away, father, and leave me alone!” she had cried. “Haven't I told you I have some important work to do?”

“Whatâat this time in the morning?” Matthew Allister's business hours were ten to five and he rarely exceeded them. On the few occasions that he broke this rule he protested that the end of the world must be coming.

“Yes; it's to do with the court-martial and its secret.”

Outside the door, the banker turned to look at Dr. McColl and shook his head.

“She always did do what she wanted to doâI wish her mother hadn't died.”

With her eyes fixed on the print, and her fingers swiftly turning the pages, Rosemary had become absorbed in the chapter devoted to this special branch of modern espionage. With morbid fascination she had read of the tremendous use to which various kinds of secret inks had been put by spies in the Great War. While the many forms of sympathetic or “invisible” inks had been known for centuries, she discovered, their development for Secret Service purposes had not been generally utilised until after 1914. Even the Germans, who were supposed to be past masters at every branch of espionage, had not developed this particular kind of spy communication to any great extent. There was one case of a German agent, she read, whose lifeâand, what was of more concern to his employers than his life, the vitally important information he had securedâmight have been saved if his instructors had given him, in the early days of the War, even an elementary insight into the uses of secret ink.

Rosemary, feeling more certain every moment that her intuition was correct concerning the two sheets of paper resting by her left hand, had then become informed through the medium of the authority she was reading that the German Secret Service, once they realised the importance of invisible inks, used at first very informally onion, lemon-juice, and even saliva. These liquids, whose properties were physical rather than chemical (the writer continued) could readily be made visible to the counter-spy either by treatment with iodine vapour or by colouring baths.

She had stopped to look at the two sheets of apparently blank paper which, before many hours were past, she was determined should be placed before experts. Did the honour and freedom of the boy she loved depend on whether her surmise was correct? She believed so.

Turning back to the book, she had read:

It was early in 1915 that the first of the truly invisible inks began to appear. For it was not until then that the Germans discovered how easily their secret correspondence was being read by the Allies. Once this discovery was made, they called in many expert chemistsâbut there were equally clever brains on the other side, and as quickly as a new ink was invented the secret was solved by French and British chemists.

It naturally followed that the inks with which German spies were provided became more and more scientific.â¦

She had stopped reading again. Her brain was becoming bewildered; the references to preliminary baths in solutions of hyposulphite and ammonia, solutions of metallic or organic salts, organic silver compounds, and proteinates confused her. Ronstadt had taken over many of Germany's former secrets and, no doubt, had raised them to a much higher degree of proficiency. Would the British chemists, to whom those two sheets of paper would be submitted, be able to find out their secret? The possibility of their failing almost prostrated her.

It was only when the print had begun to swim before her eyes and her head ached intolerably that she had risen from the chair. She had realised then, that it would be impossible for her to do anything by herself. She must wait until she saw Sir Brian Fordinghame.â¦

The Chief of Y.1 had listened to her intently.

“It's a very remarkable story,” he had commented, “and I should not be the least bit surprised if you were right, Rosemary.” (He had dropped into the habit recently of addressing her by her Christian name.)

“Then you will get the papers tested for any secret writing, Sir Brian?”

“Immediately.”

“Oh, thank you.”

Fordinghame had given her one of his honest-to-God stares.

“You still believe Wingate innocent?”

“Of courseâI've never allowed myself to think anything else.”

The Chief of Y.1 then had picked up the two sheets of lightish blue paper and risen from his chair.

“It may sound a strange thing to you, Rosemaryâbut so do I,” he had remarked.â¦

Ten minutes later, the time had arrived for them both to go to the Court. Fordinghame had assured her that, while they were at the court-martial, every known test would be applied to the papers and that, if they did contain invisible writing, it would certainly be exposed.

With what hope she had waited!

And now all that hope had been dashed to the ground. According to what the Chief of Y.1 had just told her, every re-agent known to modern science had been tried out on both the sheets of paper and no result whatever had been obtained.

The whole scheme was a complete washout.

And she had been so confident of success! She was not going to allow Bobby to sacrifice himself through his loyalty to a woman whom he had known for only a couple of days and who had made no effort at all to come forward and testify on his behalf at the court-martial. Neither had Minna Braun, or Adrienne Grandin, or whatever her name was supposed to be, sent a single word, so far as she knew, of regret at having ruined a promising boy's career before it could really be said to have started. As for what Bobby might say afterwards about her action, she completely disregarded this factor; there was only one thing to be considered and that was how to clear him of the odious charge of which, unless a miracle happened, it seemed certain, after the Judge-Advocate's summing-up speech, he would be declared guilty.

She lowered her face, unable to meet Bobby's eyes. What torture was reflected in his face! What he must have suffered! And now she could do nothing to help him. If only these sheets had revealed their secret, she would have insisted on giving evidenceâSir Brian Fordinghame had promised to give his support in thisâand then she would have told the whole story of the package so far as she was concerned. Fordinghame had told her that the President would allow her to be sworn: any evidence for the defence would be taken right up to the finding of the Court being announced. The accused was always given the utmost latitude in this respect: that was the invariable law at all General Courts-Martial.

It had been merely a mirageâ¦a vain hopeâ¦a mocking illusion.â¦

***

The members of the Court were filing back. The verdict that they had decided to bring in could be seen written on all their faces. Rosemary had no need to take a second look: Bobby, she knew, would be declared guilty!

In her distress she swung an arm out convulsively. A touch on the shoulder by Sir Brian Fordinghame made her realise what she had done: a small bottle of fountain-pen ink, from which she had been accustomed to fill her Waterman, had tipped over, and the contents were flowing all over the desk.

“Your sleeve, my dear!” said the Chief of Y.1 commiseratingly.

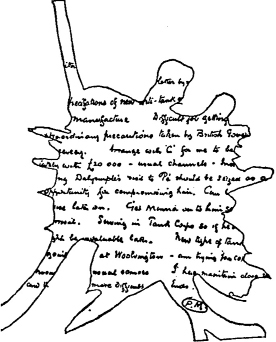

Rosemary paid him no heed: her attention was fully occupied. She continued to stare at the ink-stained sheet of paperâone of the two contained in the package.

A miracle was happeningâthe miracle of which she had dreamed, but of whose fulfilment she had utterly despaired: through the deep ink-stain which had formed,

writing was coming

.

The Traitor

Rosemary sprang up.

“Sir Brian! Look!” she criedâand caught hold of his arm as though she had suddenly been driven mad.

Fordinghame was quick to act. He took one look at the sheet which the girl extended to him so excitedly and then his voice rose high above the excited buzzing in the Court.

“I wish to apologise to you, sir, as President of the Court,” he said to the frowning chief official, “for this interruption, but something entirely unexpected has occurred.”

“May I inquire what it is?” The Accused's Friend, Peter Mallory, had crossed to the speaker's side. “What is that paper?” he asked.

Those sitting or standing near wondered why Sir Brian Fordinghame's voice had grown so stern.

“It is a very important document which has just come to light,” he said.

“Has it anything to do with the defence?” inquired Mallory, his face white.

“Yes.”

“Then I demand to see it.”

The answer was so strange that it infuriated the listener.

“I must refuse to allow it out of my hand, Mr. Mallory.”

Pandemonium suddenly broke out. If some one had not seized him from behind, Mallory would have struck the speaker. As it was, struggling in the grip of two court officials, he glared at Fordinghame as though the latter had turned from a friend into an enemy.

“I demand the fullest explanation of this extraordinary scene!” called the President. He was forced to shout to make his voice heard above the hubbub.

“I will make myself responsible for supplying it, sir.”

“You, Sir Brian?”

“Yes, General.”

While every one stared, the speaker proceeded:

“A piece of evidence, bearing strongly on this case, has suddenly turned up. May I have your permission, sir, to call a new witness?”

“Certainlyâbut I don't understand. Have you undertaken the defence of the prisoner, Sir Brian?”

“So far as the furnishing of this new evidence is concernedâyes, sir.”

Sensation.

“Call your witness.”

Fordinghame touched Rosemary Allister on the arm, and the girl walked towards the witness-box. In doing so she was forced to pass the prisoner. Everyone in the Court noticed that she gave Wingate an encouraging smile.

The Chief of Y.1 addressed the President again.

“Before I put any questions to this witness, sir, may I ask that the doors of the Court be closely guarded?”

“Are you afraid of some one trying to escape, Sir Brian?”

“Yes.”

After a nod from the President, Major Bingham, the prosecuting counsel, himself gave the necessary order. He looked completely bewildered as he returned to his seat.

“Now, Sir Brian,” said the President.

Fordinghame faced the witness.

“Your name is Rosemary Allister?”

“Yes.”

“You are the daughter of Mr. Matthew Allister, the well-known banker?”

“Yes.”

“For the past month you have been employed as assistant personal secretary to myself as Chief of the Y.1 branch of British Intelligence?”

“Yes.”

“Am I correct in saying that you have been for some time a close personal friend of the prisoner?”

“Yes.”

“Did you receive on the twentieth of September a package addressed in Lieutenant Wingate's handwriting?”

“I did.”

“Of what did that package consist?”

“It consisted of two sheets of paper enclosed in an oiled-silk covering and placed inside a copy of the Ronstadt newspaper,

Tageblatt

.”

“From where did Lieutenant Wingate send you that package?”

“From Pé.”

“Do you know for what purpose?”

“He wrote on the outsideâthat is, on the outside page of the newspaperââ

Keep this safe for me

.' ''

Waiting for the Court to digest this piece of information, the man who had so unexpectedly superseded the Accused's Friend in conducting the defence (thereby transferring himself from a powerful member of the prosecution into an ally) proceeded.

“Now I want you, Miss Allister, to tell the Court in your own words exactly what followed your receiving this package.”

The witness looked straight at the prosecuting counsel as she replied.

“I realised that Lieutenant Wingate must have had a very good reason for sending it to me, and when he came back to London I questioned him about it. He told me that the package had been given him for safe-keeping by a woman in Pé who had said that it was vitally important to both their countriesâthat was, England and Franceâthat it should be kept safe. Mr. Wingate went on to tell me that this woman had said she was a French Secret Service agent, and that he believed her.”

The President interposed a question.

“You have been in Court throughout this court-martial?”

“Yes.”

“You have therefore heard all the evidence?”

“Yes.”

“Then why have you not brought the contents of this package to the notice of the Court before?”

“I will explain,” promptly replied the witness. “Curious to know what was inside the package, I took the liberty of opening it, but was disappointed to find that all it contained were two perfectly blank sheets of paper. This made me come to the conclusionâlater, of course, when I heard the full circumstancesâthat Lieutenant Wingate had been fooled by this woman.”

“But you still kept the sheets of paper?”

“Yes.”

“Why?”

“Because, in the first place, the prisoner”âshe hesitated a little over the wordâ“had entrusted the package to me, and then, secondly, because I had a vague feeling always that I ought not to throw them away. I cannot give a better explanation than that. That was why I kept them locked in a bureau drawer in my bedroom. Last night”âshe spoke more slowly nowâ“I had my intuition confirmed.”

“Please tell the Court what happened last night, Miss Allister,” said Sir Brian Fordinghame.

“A man broke into the house and entered my bedroom. He was masked, so that I could not see his face, but I knew why he had come: his purpose was to secure the two sheets of paper which had been in the package. It made me realise that there must be some secret attached to themâand now we know what it is.”

“They contained secret writing?” interjected the prosecuting counsel.

“Yes. Sir Brian Fordinghame will show you.”

It did not seem in any way unusual that this remarkably attractive girl of twenty-two should have become the strongest character in the Court and that she should be dominating the proceedings. Even Sir Brian Fordinghame seemed to recognise that their previous relations had been changed; in any case, he obeyed the request of the girl and walked towards the seats occupied by the President and the Judge-Advocate, placing before them the piece of paper on which the ink had formed such a large blob.

Both officials were seen to lean forward to study the document intently.

Then they looked at each other, amazed. The President beckoned Major Bingham; and the prosecuting counsel, who had been frowning during the short time that it had taken Rosemary to give her evidence, walked quickly forward.

The paper was passed to him; he read it and whispered something in the ear of the President. The latter, after conferring briefly with the Judge-Advocate, nodded.

“Gentlemen,” he said, addressing the other members of the court-martial, “it is my duty to inform you that very important evidenceâevidence which you must hear before I ask you for your findings in this caseâhas just come to light. I call upon Sir Brian Fordinghame.”

The Chief of Y.1 went to the witness stand and took the oath. Meanwhile, the reporters turned curiously to each other; this case, which had already been crammed with drama, looked as if it would provide an extraordinary dénouement.

Strangely enough, it was the prosecuting counsel who started to question this new witness. Standing at some distance away from every one else, the man who should have undertaken the taskâPeter Malloryâsurveyed the proceedings with what looked like a sardonic smile on his gaunt face. He had one hand in his coat pocket.

“You are the Chief of the Y.1 branch of British Intelligence?” Major Bingham asked the new witness.

“Yes.”

“In that capacity it has been your duty to prepare the facts for the present charge against the prisoner?”

“Yes.”

“You corroborate all that Miss Rosemary Allister has already told the Court?”

“I do. May I go on?”

“Yes, please, Sir Brian.”

“Directly I arrived at the office this morning I found Miss Allister in a great state of excitement. She told me of the attempted burglary the night before, and said that she had spent several hours reading up all the available facts about secret inks. She implored me to put the two sheets of paper in question to every possible testâwhich I did.”

“With any result?”

“None. All the usual re-agents failed.”

“And yet ordinary fountain-pen ink brought out the writing?”

“That is so.”

Major Bingham took some time before asking the next question. When he did so his voice sounded like the voice of doom.

“Sir Brian Fordinghame, I have now to put to you a very important question: do you recognise the handwriting on this paper?” holding it up.

“I do.”

“You must tell the Court what person, in your opinion, supplied this secret informationânamely, the very facts on which the first charge in this prosecution against Lieutenant Robert Wingate has been basedâto the Ronstadt agents.”

The answer seemed dragged from the witness. He evidently spoke with the utmost reluctance.

“I am sorry to say,” he returned slowly, “that these details concerning the new anti-tank shoulder weapon, which Lieutenant Robert Wingate was supposed to have supplied to Ronstadt, are in the handwriting ofâ”

He was obliged to stop. A heavy crashâlike that which might have been made by the sound of a body fallingâhad diverted not only his attention but the attention of every one in the crowded court.

A man was seen twitching in agony on the floor.

“My God!” shrieked a reporter, forgetting all professional decorum in the excitement of the moment. “

Mallory was the traitor!

”