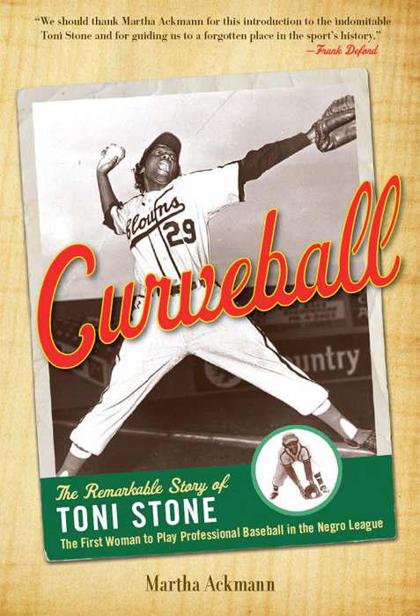

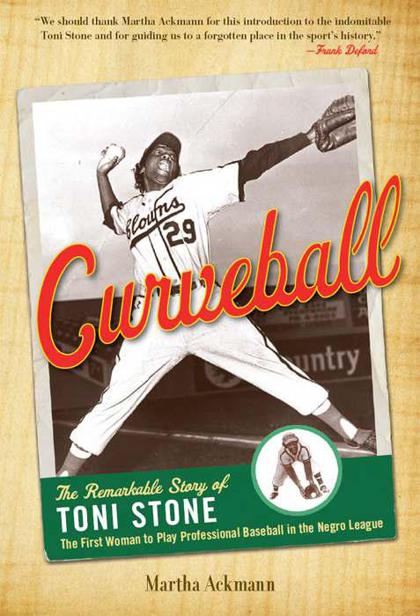

Curveball

Authors: Martha Ackmann

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ackmann, Martha.

Curveball : the remarkable story of Toni Stone the first woman to play professional baseball in the negro league / Martha Ackmann.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-55652-796-8 (hardcover)

1. Stone, Toni, 1921-1996. 2. Baseball players—United States—Biography. 3. African American baseball players—Biography. 4. Women baseball players—United States. I. Title.

GV865.S86A35 2010

796.357092—dc22

[B] 2010007019

“They Went Home” from JUST GIVE ME A COOL DRINK OF WATER ’FORE I DIE by Maya Angelou, copyright © 1971 by Maya Angelou. Used by permission of Random House, Inc.

“A Song in the Front Yard” reprinted by consent of Brooks Permission.

Interior design: Scott Rattray

© 2010 by Martha Ackmann

All rights reserved

Published by Lawrence Hill Books

An imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-55652-796-8

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

In memory of N. Jean Fields

(1932–1998)

“It’s noble to be good, and it’s nobler to teach

others to be good, and less trouble.”

—Mark Twain

3 Barnstorming with the Colored Giants

5 Finding the Heart of the Game

You’re supposed to step into a curveball, not away from it.

—T

HOMAS

B

URT

, I

NDIANAPOLIS

C

LOWNS

,

N

EGRO

A

MERICAN

L

EAGUE

1

T

oni Stone got suspicious when the occasional stranger called to ask about her remarkable baseball career. She had seen a lot of fools, and the seventy-two-year-old woman’s guard went up immediately if she thought someone seemed interested in using her. Toni had learned the hard way that people could take advantage of her: someone once took some of her precious team photographs guaranteeing to “get Toni Stone the recognition she deserved” and then vanished with promises unmet and photos pocketed. Then there were the reporters who played fast and loose with the truth, trying to “improve” her story so that she would appear more sophisticated, better educated, or more feminine. She hated the inaccuracies, which she called “ad libs.” It was like a jazz riff, she said, the ad lib. “I don’t want no ad libbing. I want my real thing.”

2

In 1993, when baseball historian Kyle McNary called her on the phone, Toni wasn’t sure she wanted to talk to him. The two had never met, and she warily suspected that McNary might be just another person wanting to “capitalize of me.” She hated it when sportswriters claimed to rediscover her, then portrayed her as a sideshow oddity—a strange woman who long ago wanted to play baseball with the boys. It angered and hurt her when they turned her commitment to the game into a freak show. “I’m getting ready to go away,” Toni told McNary, leaving herself an opening to end the conversation if he turned out to be just another someone who wanted to make a buck. “I won’t be back until the middle of the month.” But when the earnest young man spoke to Toni about how much he loved baseball and only wanted to know more about her days in the Negro League, she warmed to him. Playing professional baseball had been the highlight of Toni’s life, and, as painful as some of the memories were, she freely admitted she had more good recollections than bad. With each question McNary asked, a rush of images flooded her mind: a cast-off baseball glove bought at the Goodwill, junker automobiles in the 1930s full of hungry players touring the Dakotas, jazz clubs hot with music, crowds of reporters straining to get a look at the girl playing Negro League ball, a newspaper story proclaiming Toni Stone “the greatest attraction to hit the loop since Leroy ‘Satchel’ Paige.”

3

No other woman ever matched Toni Stone’s accomplishments in baseball—during her nearly two decades of play or since. She was the first woman to play professional baseball on men’s teams in the Negro League of the 1950s. When a young Henry Aaron moved from the Indianapolis Clowns to the majors, Stone replaced him on the team. “She was a very good baseball player,” Aaron said.

4

Known as a tenacious athlete with quick hands, a competitive bat, and a ferocious spirit, Toni was a pro and “smooth,” according to Ernie Banks.

5

Yet her story is about much more than baseball. It is also about confronting the ugly realities of Jim Crow America, in the days before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on the bus. Some of those stories Toni would share, and others were too difficult for her to admit—sometimes even to herself. There were memories of hurled epithets from the grandstands, “Whites Only” signs on railroad cars, and waitresses who would spit in glasses of Coke before serving them to black customers. During segregation, if you were a young African American woman and you wanted to play second base more than anything else in the world, you were in for a rough ride.

When Toni began to relax and talk less cautiously with him, McNary admitted to her that he was surprised by how young shesounded when she answered the phone. Everyone who met Toni for the first time was momentarily startled by her odd, breathless, high-pitched voice. It made her sound small and insistent, like a child struggling to be heard. Toni explained that once when she was young she mistakenly drank some Sloan’s Liniment, an over-the-counter rub for stiff muscles. “It did me in, changed my voice,” she said.

6

She joked about the way her voice sounded with a well-rehearsed line. “When I wanted to demand something, I had to use a whistle and a baseball bat,” she said. “A whistle and a baseball bat.” There was a tinge of weariness in her response, as if she had long ago grown tired of explaining herself.

7

Stone eased herself into a chair by the phone to continue talking. Her knees ached, but she rarely complained, and she would not let the pain stop her. Toni was too full of pride. She could still climb a ladder and paint a ceiling if she needed to, and she was legendary in her family for doing her own repair work. Aunt Toni “could really put on a set of steps,” her niece would say.

8

Stone’s house—a small Victorian gem on Isabella Street in Oakland, California, had been her home for nearly fifty years after she left Saint Paul, Minnesota. “She needed to get away,” relatives said. Saint Paul had grown too small for Toni, and she always had her eye on the next horizon.

When she was barely a teenager, people had already noticed that Toni Stone was far from ordinary. She was an astonishing athlete who seemed to excel at everything she attempted: swimming, golf, track, basketball, hockey, tennis, ice skating. She was even the most feared kid in the neighborhood when it came to playing red rover. She made a point of always breaking through the strongest link in the chain, just to prove she was tough.

9

But baseball won her heart. “Tomboy” Stone, as neighborhood kids called her, eventually became so well known in Saint Paul that when her younger sister announced her engagement the newspaper mistakenly ran a photograph of Toni instead of her sibling.

10

Editors, used to putting Toni in the paper, had hastily inserted the wrong photograph. But they got it right when the newspaper imagined a future for Tomboy that would extend well beyond Minnesota. “We do not hesitate,” the

Minneapolis Spokesman

declared in 1937, “to predict that she some day will acquire the fame of one Babe” Didrikson.

11

Years later Toni would state matter-of-factly, “I could outscore her and out hit her.” Many agreed. Ball players who later faced both Didrikson and Stone on the baseball diamond confirmed, “Babe was a pretty good player, but Toni Stone was a

real

good player.”

12

After she left Saint Paul, Stone went to San Francisco, then New Orleans, and traveled with semi-pro teams throughout the South. “I love my San Francisco. I had my hardships there. But they treated me right. Old San Francisco folks taken me over,” she said, her voice becoming softer. “I played ball. And I got a little job. I slept in the [bus] station. I have beautiful memories and very little bad ones. I guess it’s a way of carrying myself.”

Working hard was a virtue Stone learned from her parents. Boykin and Willa Stone moved to Saint Paul in the 1930s and started a business. Every day, Toni came home from school—or from skipping school—and knew her parents would not be home until late at night. Their drive to make something of themselves left an impression. “I watched my folks come home and scuffle. It was during the Depression and I watched them work hard. And I said, ‘If I can’t be among the best, then I’ll just leave it alone.’”

“Scuffle” was an important word to Stone. She used it to underscore the grit needed to work against the odds: resolve, persistence, sacrifice. It was the price people were willing to pay to do what they loved. If anyone suggested that playing black baseball was an easy road, she bristled and her thin voice became pinched and direct. “They never was in it!” she argued. “Those old timers, they really had to scuffle and darn near get killed going down the highway, run onto some snakes that tore the bus up.” During a time when a black person could be lynched for smiling the “wrong way,” a busload of African American ballplayers looking for a place to stay overnight threatened bigots on either side of the Mason-Dixon line. She hinted briefly at an incident triggered by the double prejudice she faced as an African American woman, but she stopped short before fully describing what happened. “You see, I fought a lot,” she admitted, “but they broke me of it. The fellas said they’d liable kill me.” Keeping the degradation she experienced from imploding inside her was perhaps what Stone meant by finding “a way of carrying herself.” A person had to listen carefully to Toni Stone.