The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy (103 page)

Read The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy Online

Authors: Irvin D. Yalom,Molyn Leszcz

Tags: #Psychology, #General, #Psychotherapy, #Group

Feedback

Feedback, a term borrowed from electrical engineering, was first applied to the behavioral sciences by Lewin (who was teaching at MIT at the time).

3

The early group leaders considered that an important flaw in society was that too little opportunity existed for individuals to obtain accurate feedback from their “back-home” associates—bosses, coworkers, husbands, wives, teachers. Feedback, which became an essential ingredient of all T-groups (and later, of course, all interactional therapy groups) was found to be most effective when it stemmed from here-and-now observations, when it followed the generating event as closely as possible, and when the recipient checked it out with other group members to establish its validity and reduce perceptual distortion.

Observant Participation

The early T-group leaders considered

observant participation

the optimal method of group participation. Members must not only engage emotionally in the group, but they must simultaneously and objectively observe themselves and the group. Often this is a difficult task to master, and members chafe at the trainer’s attempts to subject the group to objective analysis. Yet the dual task is essential to learning; alone, either action or intellectual scrutiny yields little learning. Camus once wrote, “My greatest wish: to remain lucid in ecstasy.” So, too, the T-group (and the therapy group, as well) is most effective when its members can couple clarity of vision with emotional experience.

Unfreezing

Unfreezing, also adopted from Lewin’s change theory,

4

refers to the process of disconfirming an individual’s former belief system. Motivation for change must be generated before change can occur. One must be helped to reexamine many cherished assumptions about oneself and one’s relations to others. The familiar must be made strange; thus, many common props, social conventions, status symbols, and ordinary procedural rules were eliminated from the T-group, and one’s values and beliefs about oneself were challenged. This was a most uncomfortable state for group participants, a state tolerable only under certain conditions: Members must experience the group as a safe refuge within which it is possible to entertain new beliefs and experiment with new behavior without fear of reprisal. Though “unfreezing” is not a familiar term to clinicians, the general concept of examining and challenging familiar assumptions is a core part of the psychotherapeutic process.

Cognitive Aids

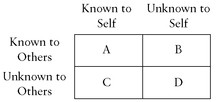

Cognitive guides around which T-group participants could organize their experience were often presented in brief lecturettes by T-group leaders. This practice foreshadowed and influenced the current widespread use of cognitive aids in contemporary psychoeducational and cognitive-behavioral group therapy approaches. One example used in early T-group work (I choose this particular one because it remains useful in the contemporary therapy group) is the Johari window

5

a four-cell personality paradigm that clarifies the function of feedback and self-disclosure.

Cell A, “Known to self and Known to others,” is the public area of the self; cell B, “Unknown to self and Known to others,” is the blind area; cell C, “Known to self and Unknown to others,” is the secret area; cell D, “Unknown to self and Unknown to others,” is the unconscious self. The goals of the T-group, the leader suggests, are to increase the size of cell A by decreasing cell B (blind spots) through feedback and cell C (secret area) through self-disclosure. In traditional T-groups, cell D (the unconscious) was considered out of bounds.

GROUP THERAPY FOR NORMALS

In the 1960s, the clinically oriented encounter group leaders from the West Coast began endorsing a model of a T-group as “group therapy for normals.” They emphasized personal growth,

6

and though they still considered the experiential group an instrument of education, not of therapy, they offered a broader, more humanistically based definition of education. Education is not, they argued, the process of acquiring interpersonal and leadership skills, not the understanding of organizational and group functioning; education is nothing less than comprehensive self-discovery, the development of one’s full potential.

These group leaders worked with normal healthy members of society, indeed with individuals who, by most objective standards, had achieved considerable success yet still experienced considerable tension, insecurity, and value conflict. They noted that many of their group members were consumed by the building of an external facade, a public image, which they then strove to protect at all costs. Their members swallowed their doubts about personal adequacy and maintained constant vigilance lest any uncertainty or discomfort slip into visibility.

This process curtailed communication not only with others but with themselves. The leaders maintained that in order to eliminate a perpetual state of self-recrimination, the successful individual gradually comes to believe in the reality of his or her facade and attempts, through unconscious means, to ward off internal and external attacks on that self-image. Thus, a state of equilibrium is reached, but at great price: considerable energy is invested in maintaining intrapersonal and interpersonal separation, energy that might otherwise be used in the service of self-actualization. These leaders set ambitious goals for their group—no less than addressing and ameliorating the toxic effects of the highly competitive American culture.

As the goal of the group shifted from education in a traditional sense to personal change, the names of the group shifted from T-group (training in human relations) or sensitivity training group (training in interpersonal sensitivity), to ones more consonant with the basic thrust of the group. Several labels were advanced: “personal growth” or “human potential” or “human development” groups. Carl Rogers suggested the term “encounter group,” which stressed the basic authentic encounter between members and between leader and members and between the disparate parts of each member. His term had the most staying power and became the most popular name for the “let it all hang out” experiential group prevalent in the 1960s and 1970s.

The third force in psychology (third after Freudian analysis and Watsonian-Skinnerian behaviorism), which emphasized a holistic, humanistic concept of the person, provided impetus and form to the encounter group from yet another direction. Psychologists such as A. Maslow, G. Allport, E. Fromm, R. May, F. Perls, C. Rogers, and J. Bugenthal (and the existential philosophers behind them—Nietzsche, Sartre, Tillich, Jaspers, Heidegger, and Husserl), rebelled strongly against the mechanistic model of behaviorism, the determinism and reductionism of analytic theory. Where, they asked, is the person? Where is consciousness, will, decision, responsibility, and a recognition and concern for the basic and tragic dimensions of existence?

All of these influences resulted in groups with a much broader, and vaguer, goal—nothing less than “total enhancement of the individual.” Time in the group was set aside for reflective silence, for listening to music or poetry. Members were encouraged to give voice to their deepest concerns—to reexamine these basic life values and the discrepancies between them and their lifestyles, to encounter their many false selves; to explore the long-buried parts of themselves (the softer, feminine parts in the case of men, for example).

Collision with the field of psychotherapy was inevitable. Encounter groups claimed that they offered therapy for normals, yet also that “normality” was a sham, that

everyone

was a patient. The disease? A dehumanized runaway technocracy. The remedy? A return to grappling with basic problems of the human condition. The vehicle of remedy? The encounter group! In their view the medical model could no longer be applied to mental illness. The differentiation between mental illness and health grew as vague as the distinction between treatment and education. Encounter group leaders claimed that patienthood is ubiquitous, that therapy is too good to be limited to the sick, and that one need not be sick to get better.

The Role of the Leader

Despite the encroachment of encounter groups on the domain of psychotherapy, there were many striking differences in the basic role of group therapist and encounter group leader. At the time of the emergence of the encounter group, many group therapists assumed entirely different rules of conduct from the other members. They merely transferred their individual therapy psychoanalytic style to the group arena and remained deliberately enigmatic and mystifying. Rarely transparent, they took care to disclose only a professional front, with the result that members often regarded the therapist’s statements and actions as powerful and sagacious, regardless of their content.

Encounter group leaders had a very different code of conduct. They were more flexible, experimental, more self-disclosing, and they earned prestige as a result of their contributions. The group members regarded encounter group leaders far more realistically and similar to themselves except for their superior skill and knowledge in a specialized area. Furthermore, the leaders sought to transmit not only knowledge but also skills, expecting the group members to learn methods of diagnosing and resolving interpersonal problems. Often they explicitly behaved as teachers—for example, explicating some point of theory or introducing some group exercise, verbal or nonverbal, as an experiment for the group to study. It is interesting, incidentally, to note the reemergence of flexibility and the experimental attitude displayed by contemporary therapy group leaders in the construction of cognitive-behavioral group formats addressing a wide number of special problems and populations.

THE EFFECTIVENESS OF THE ENCOUNTER GROUP

In its early days the social psychologists involved with T-groups painstakingly researched their process and outcome. Many of these studies still stand as paradigms of imaginative, sophisticated research.

The most extensive controlled research inquiry into the effectiveness of groups that purport to change behavior and personality was conducted by Lieberman, Yalom, and Miles in 1973. This project has much relevance to group therapy, and since I draw from its findings often in this book I will describe the methodology and results briefly. (The design and method are complex, and I refer interested, research-minded readers to the previous edition’s version of this chapter at

www.yalom.com

or, for a complete description, to the monograph on the study,

Encounter Groups: First Facts

.)

7

The Participants

We offered an experiential group as an accredited course at Stanford University. Two hundred ten participants were randomly assigned to one of eighteen groups, each of which met for a total of thirty hours over a twelve-week period. Sixty-nine subjects, similar to the participants but who did not have a group experience, were used as a control population and completed all the outcome research instruments.

The Leaders

Since a major aim of the study was to investigate the effect of leader technique on outcome, we sought to diversify leader style by employing leaders from several ideological schools. We selected experienced and expert leaders from ten such schools that were currently popular:

1. Traditional T-groups

2. Encounter groups (personal growth group)

3. Gestalt groups

4. Sensory awareness groups (Esalen group)

5. Transactional analytic (TA) groups

6. Psychodrama groups

7. Synanon groups

8. Psychoanalytically oriented experiential groups

9. Marathon groups

10. Encounter-tapes (leaderless) groups

There were a total of eighteen groups. Of the 210 subjects who started in the eighteen groups, 40 (19 percent) dropped out before attending half the meetings, and 170 finished the thirty-hour group experience.

What Did We Measure?

We were most interested in an intensive examination of outcome as well as the relationship between outcome, leader technique, and group process variables. To evaluate outcome, an extensive psychological battery of instruments was administered to each subject three times—before beginning the group, immediately after completing it, and six months after completion.

8

To measure leader style, teams of trained raters observed all meetings and coded all behavior of the leader in real time. All statements by the leaders were also coded by analyzing tape recordings and written transcripts of the meetings. Participants also supplied observations of the leaders through questionnaires. Process data was collected by the observers and from questionnaires filled out by participants at the end of each meeting.