The Tale of Despereaux (12 page)

Read The Tale of Despereaux Online

Authors: Kate DiCamillo

“That’s right,” said Cook. “Seems simple, don’t it? But I’m sure you’ll find a way to bungle it.”

“Eh?” said Mig.

“Nothing,” said Cook. “Good luck to you. You’ll be needing it.”

She watched as Mig descended the dungeon stairs. They were the very same stairs, reader, that the mouse Despereaux had been pushed down the day before. Unlike the mouse, however, Mig had a light: on the tray with the food, there was a single, flickering candle to show her the way. She turned on the stairs and looked back at Cook and smiled.

“That cauliflower-eared, good-for-nothing fool,” said Cook, shaking her head. “What’s to become of someone who goes into the dungeon smiling, I ask you?”

Reader, for the answer to Cook’s question, you must read on.

THE TERRIBLE FOUL ODOR of the dungeon did not bother Mig. Perhaps that is because, sometimes, when Uncle was giving her a good clout to the ear, he missed his mark and delivered a good clout to Mig’s nose instead. This happened often enough that it interrupted the proper workings of Mig’s olfactory senses. And so it was that the overwhelming stench of despair and hopelessness and evil was not at all discernible to her, and she went happily down the twisting and turning stairs.

“Gor!” she shouted. “It’s dark, ain’t it?”

“Yes, it is Mig,” she answered herself, “but if I was a princess, I would be so glittery lightlike, there wouldn’t be a place in the world that was dark to me.”

At this point, Miggery Sow broke into a little song that went something like this:

“

I ain’t the Princess Pea

But someday I will be,

The Pea, ha-hee.

Someday, I will be.

”

Mig, as you can imagine, wasn’t much of a singer, more of a bellower, really. But in her little song, there was, to the rightly tuned ear, a certain kind of music. And as Mig went singing down the stairs of the dungeon, there appeared from the shadows a rat wrapped in a cloak of red and wearing a spoon on his head.

“Yes, yes,” whispered the rat, “a lovely song. Just the song I have been waiting to hear.”

And Roscuro quietly fell in step beside Miggery Sow.

At the bottom of the stairs, Mig shouted out into the darkness, “Gor, it’s me, Miggery Sow, most calls me Mig, delivering your food! Come and get it, Mr. Deep Downs!”

There was no response.

The dungeon was quiet, but it was not quiet in a good way. It was quiet in an ominous way; it was quiet in the way of small, frightening sounds. There was the snail-like slither of water oozing down the walls and from around a darkened corner there came the low moan of someone in pain. And then, too, there was the noise of the rats going about their business, their sharp nails hitting the stones of the dungeon and their long tails dragging behind them, through the blood and muck.

Reader, if you were standing in the dungeon, you would certainly hear all of these disturbing and ominous sounds.

If I were standing in the dungeon,

I

would hear these sounds.

If we were standing together in the dungeon, we would hear these sounds and we would be very frightened; we would cling to each other in our fear.

But what did Miggery Sow hear?

That’s right.

Absolutely nothing.

And so she was not afraid at all, not in the least.

She held the tray up higher, and the candle shed its weak light on the towering pile of spoons and bowls and kettles. “Gor,” said Mig, “look at them things. I ain’t never imagined there could be so many spoons in the whole wide world.”

“There is more to this world than anyone could imagine,” said a booming voice from the darkness.

“True, true,” whispered Roscuro. “The old jailer speaks true.”

“Gor,” said Mig. “Who said that?” And she turned in the direction of the jailer’s voice.

THE CANDLELIGHT on Mig’s tray revealed Gregory limping toward her, the thick rope tied around his ankle, his hands outstretched.

“You, Gregory presumes, have brought food for the jailer.”

“Gor,” said Mig. She took a step backward.

“Give it here,” said Gregory, and he took the tray from Mig and sat down on an overturned kettle that had rolled free from the tower. He balanced the tray on his knees and stared at the covered plate.

“Gregory assumes that today, again, there is no soup.”

“Eh?” said Mig.

“Soup!” shouted Gregory.

“Illegal!” shouted Mig back.

“Most foolish,” muttered Gregory as he lifted the cover off the plate, “too foolish to be borne, a world without soup.” He picked up a drumstick and put the whole of it in his mouth and chewed and swallowed.

“Here,” said Mig, staring hard at him, “you forgot the bones.”

“Not forgotten. Chewed.”

“Gor,” said Mig, staring at Gregory with respect. “You eats the bones. You are most ferocious.”

Gregory ate another piece of chicken, a wing, bones and all. And then another. Mig watched him admiringly.

“Someday,” she said, moved suddenly to tell this man her deepest wish, “I will be a princess.”

At this pronouncement, Chiaroscuro, who was still at Mig’s side, did a small, deliberate jig of joy; in the light of the one candle, his dancing shadow was large and fearsome indeed.

“Gregory sees you,” Gregory said to the rat’s shadow.

Roscuro ceased his dance. He moved to hide beneath Mig’s skirts.

“Eh?” shouted Mig. “What’s that?”

“Nothing,” said Gregory. “So you aim to be a princess. Well, everyone has a foolish dream. Gregory, for instance, dreams of a world where soup is legal. And that rat, Gregory is sure, has some foolish dream, too.”

“If only you knew,” whispered Roscuro.

“What?” shouted Mig.

Gregory said nothing more. Instead, he reached into his pocket and then held his napkin up to his face and sneezed into it, once, twice, three times.

“Bless you!” shouted Mig. “Bless you, bless you.”

“Back to the world of light,” Gregory whispered. And then he balled the napkin up and placed it on the tray.

“Gregory is done,” he said. And he held the tray out to Mig.

“Done are you? Then the tray goes back upstairs. Cook says it must. You take the tray to the deep downs, you wait for the old man to eat, and then you bring the tray back. Them’s my instructions.”

“Did they instruct you, too, to beware of the rats?”

“The what?”

“The rats.”

“What about ’em?”

“Beware of them,” shouted Gregory.

“Right,” said Mig. “Beware the rats.”

Roscuro, hidden beneath Mig’s skirts, rubbed his front paws together. “Warn her all you like, old man,” he whispered. “My hour has arrived. The time is now and your rope must break. No nib-nib-nibbling this time, rather a serious chew that will break it in two. Yes, it is all coming clear. Revenge is at hand.”

MIG HAD CLIMBED the dungeon stairs and was preparing to open the door to the kitchen, when the rat spoke to her.

“May I detain you for a moment?”

Mig looked to her left and then to her right.

“Down here,” said Roscuro.

Mig looked at the floor.

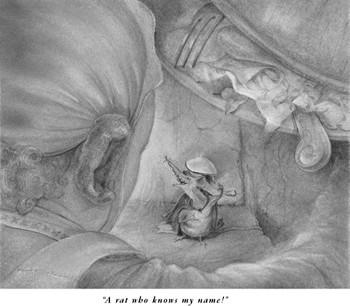

“Gor,” she said, “but you’re a rat, ain’t you? And didn’t the old man just warn me of such? ‘Beware the rats,’ he said.” She held the tray up higher so that the light from the candle shone directly on Roscuro and the golden spoon on his head and the blood-red cloak around his neck.

“There is no need to panic, none at all,” said Roscuro. As he talked, he reached behind his back and, using the handle, he raised the soupspoon off his head, much in the manner of a man lifting his hat to a lady.

“Gor,” said Mig, “a rat with manners.”

“Yes,” said Roscuro. “How do you do?”

“My papa had him some cloth much like yours, Mr. Rat,” said Mig. “Red like that. He traded me for it.”

“Ah,” said Roscuro, and he smiled a large, knowing smile. “Ah, did he really? That is a terrible story, a tragic story.”

Reader, if you will pardon me, we must pause for a moment to consider a great and unusual thing, a portentous thing. That great, unusual, portentous thing is this: Roscuro’s voice was pitched perfectly to make its way through the tortuous path of Mig’s broken-down, cauliflower ears. That is to say, dear reader, Miggery Sow heard, perfect and true, every single word the rat Roscuro uttered.

“You have known your share of tragedy,” said Roscuro to Mig. “Perhaps it is time for you to make the acquaintance of triumph and glory.”

“Triumph?” said Mig. “Glory?”

“Allow me to introduce myself,” said Roscuro. “I am Chiaroscuro. Friends call me Roscuro. And your name is Miggery Sow. And it is true, is it not, that most people call you simply Mig?”

“Ain’t that the thing?” shouted Mig. “A rat who knows my name!”

“Miss Miggery, my dear, I do not want to appear too forward so early in our acquaintance, but may I inquire, am I right in ascertaining that you have aspirations?”

“What do ye mean ‘aspirations’?” shouted Mig.

“Miss Miggery, there is no need to shout. None at all. As you can hear me, so I can hear you. We two are perfectly suited, each to the other.” Roscuro smiled again, displaying a mouthful of sharp yellow teeth. “ ‘Aspirations,’ my dear, are those things that would make a serving girl wish to be a princess.”

“Gor,” agreed Mig, “a princess is exactly what I want to be.”

“There is, my dear, a way to make that happen. I believe that there is a way to make that dream come true.”

“You mean that I could be the Princess Pea?”

“Yes, Your Highness,” said Roscuro. And he swept the spoon off his head and bowed deeply at the waist. “Yes, your most royal Princess Pea.”

“Gor!” said Mig.

“May I tell you my plan? May I illustrate for you how we can make your dream of becoming a princess a reality?”

“Yes,” said Mig, “yes.”

“It begins,” said Roscuro, “with yours truly, and the chewing of a rope.”

Mig held the tray with the one small candle burning bright, and she listened as the rat went on, speaking directly to the wish in her heart. So passionately did Roscuro speak and so intently did the serving girl listen that neither noticed as the napkin on the tray moved.