The Tale of Despereaux (10 page)

Read The Tale of Despereaux Online

Authors: Kate DiCamillo

MIGGERY SOW called the man who purchased her Uncle, as he said she must. And also, as he said she must, Mig tended Uncle’s sheep and cooked Uncle’s food and scrubbed Uncle’s kettle. She did all of this without a word of thanks or praise from the man himself.

Another unfortunate fact of life with Uncle was that he very much liked giving Mig what he referred to as “a good clout to the ear.” In fairness to Uncle, it must be reported that he did always inquire whether or not Mig was interested in receiving the clout.

Their daily exchanges went something like this:

Uncle: “I thought I told you to clean the kettle.”

Mig: “I cleaned it, Uncle. I cleaned it good.”

Uncle: “Ah, it’s filthy. You’ll have to be punished, won’t ye?”

Mig: “Gor, Uncle, I cleaned the kettle.”

Uncle: “Are ye saying that I’m a liar, girl?”

Mig: “No, Uncle.”

Uncle: “Do ye want a good clout to the ear, then?”

Mig: “No, thank you, Uncle, I don’t.”

Alas, Uncle seemed to be as entirely unconcerned with what Mig wanted as her mother and father had been. The discussed clout to the ear was always delivered . . . delivered, I am afraid, with a great deal of enthusiasm on Uncle’s part and received with absolutely no enthusiasm at all on the part of Mig.

These clouts were alarmingly frequent. And Uncle was scrupulously fair in paying attention to both the right and left side of Miggery Sow. So it was that after a time, the young Mig’s ears came to resemble not so much ears as pieces of cauliflower stuck to either side of her head.

And they became about as useful to her as pieces of cauliflower. That is to say that they all but ceased their functioning as ears. Words, for Mig, lost their sharp edges. And then they lost their edges altogether and became blurry, blankety things that she had a great deal of trouble making any sense out of at all.

The less Mig heard, the less she understood. The less she understood, the more things she did wrong; and the more things she did wrong, the more clouts to the ear she received, and the less she heard. This is what is known as a vicious circle. And Miggery Sow was right in the center of it.

Which is not, reader, where anybody would want to be.

But then, as you know, what Miggery Sow wanted had never been of much concern to anyone.

WHEN MIG TURNED SEVEN years old, there was no cake, no celebration, no singing, no present, no acknowledgment of her birthday at all other than Mig saying, “Uncle, today I am seven years old.”

And Uncle saying in return, “Did I ask ye how old you were today? Get out of my face before I give ye a good clout to the ear.”

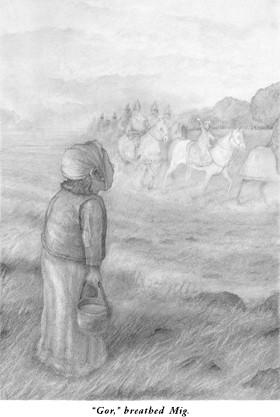

A few hours after receiving her birthday clout to the ear, Mig was out in the field with Uncle’s sheep when she saw something glittering and glowing on the horizon.

She thought for a moment that it was the sun. But she turned and saw that the sun was in the west, where it should be, sinking to join the earth. This thing that shone so brightly was something else. Mig stood in the field and shaded her eyes with her left hand and watched the brilliant light draw closer and closer and closer until it revealed itself to be King Phillip and his Queen Rosemary and their daughter, the young Princess Pea.

The royal family was surrounded by knights in shining armor and horses in shining armor. And atop each member of the royal family’s head, there was a golden crown, and they were all, the king and the queen and the princess, dressed in robes decorated with jewels and sequins that glittered and glowed and captured the light of the setting sun and reflected it back.

“Gor,” breathed Mig.

The Princess Pea was riding on a white horse that picked up its legs very high and set them down very daintily. The Pea saw Mig standing and staring, and she raised a hand to her.

“Hello,” the Princess Pea called out merrily, “hello.” And she waved her hand again.

Mig did not wave back; instead, she stood and watched, open-mouthed, as the perfect, beautiful family passed her by.

“Papa,” called the princess to the king, “what is wrong with the girl? She will not wave to me.”

“Never mind,” said the king. “It is of no consequence, my dear.”

“But I am a princess. And I waved to her. She should wave back.”

Mig, for her part, continued to stare. Looking at the royal family had awakened some deep and slumbering need in her; it was as if a small candle had been lit in her interior, sparked to life by the brilliance of the king and the queen and the princess.

For the first time in her life, reader, Mig hoped.

And hope is like love . . . a ridiculous, wonderful, powerful thing.

Mig tried to name this strange emotion; she put a hand up to touch one of her aching ears, and she realized that the feeling she was experiencing, the hope blooming inside of her, felt exactly the opposite of a good clout.

She smiled and took her hand away from her ear. She waved to the princess. “Today is my birthday!” Mig called out.

But the king and the queen and the princess were by now too far away to hear her.

“Today,” shouted Mig, “I am seven years old!”

THAT NIGHT, in the small, dark hut that she shared with Uncle and the sheep, Mig tried to speak of what she had seen.

“Uncle?” she said.

“Eh?”

“I saw some human stars today.”

“How’s that?”

“I saw them all glittering and glowing, and there was a little princess wearing her own crown and riding on a little white, tippy-toed horse.”

“What are ye going on about?” said Uncle.

“I saw a king and a queen and a itty-bitty princess,” shouted Mig.

“So?” shouted Uncle back.

“I would like . . .,” said Mig shyly. “I wish to be one of them princesses.”

“Har,” laughed Uncle. “Har. An ugly, dumb thing like you? You ain’t even worth the enormous lot I paid for you. Don’t I wish every night that I had back that good hen and that red tablecloth in place of you?”

He did not wait for Mig to guess the answer to this question. “I do,” he said. “I wish it every night. That tablecloth was the color of blood. That hen could lay eggs like nobody’s business.”

“I want to be a princess,” said Mig. “I want to wear a crown.”

“A crown.” Uncle laughed. “She wants to wear a crown.” He laughed harder. He took the empty kettle and put it atop his head. “Look at me,” he said. “I’m a king. See my crown? I’m a king just like I always wanted to be. I’m a king because I

want

to be one.”

He danced around the hut with the kettle on his head. He laughed until he cried. And then he stopped dancing and took the kettle from his head and looked at Mig and said, “Do ye want a good clout to the ear for such nonsense?”

“No, thank you, Uncle,” said Mig.

But she got one anyway.

“Look here,” said Uncle after the clout had been delivered. “We will hear no more talk of princesses. Besides, who ever asked you what you wanted in this world, girl?”

The answer to that question, reader, as you well know, was absolutely no one.

YEARS PASSED. Mig spent them scrubbing the kettle and tending the sheep and cleaning the hut and collecting innumerable, uncountable, extremely painful clouts to the ear. In the evening, spring or winter, summer or fall, Mig stood in the field as the sun set, hoping that the royal family would pass before her again.

“Gor, I would like to see that little princess another time, wouldn’t I? And her little pony, too, with his tippy-toed feet.” This hope, this wish, that she would see the princess again, was lodged deep in Mig’s heart; lodged firmly right next to it was the hope that she, Miggery Sow, could someday become a princess herself.

The first of Mig’s wishes was granted, in a roundabout way, when King Phillip outlawed soup. The king’s men were sent out to deliver the grim news and to collect from the people of the Kingdom of Dor their kettles, their spoons, and their bowls.

Reader, you know exactly how and why this law came to pass, so you would not be as surprised as Uncle was when, one Sunday, a soldier of the king knocked on the door of the hut that Mig and Uncle and the sheep shared and announced that soup was against the law.

“How’s that?” said Uncle.

“By royal order of King Phillip,” repeated the soldier, “I am sent here to tell you that soup has been outlawed in the Kingdom of Dor. You will, by order of the king, never again consume soup. Nor will you think of it or talk about it. And I, as one of the king’s loyal servants, am here to take from you your spoons, your kettle, and your bowls.”

“But that can’t be,” said Uncle.

“Nevertheless. It is.”

“What’ll we eat? And what’ll we eat it with?”

“Cake,” suggested the soldier, “with a fork.”

“And wouldn’t that be lovely,” said Uncle, “if we could afford to eat cake.”

The soldier shrugged. “I am only doing my duty. Please hand over your spoons, your bowls, and your kettle.”

Uncle grabbed hold of his beard. He let go of his beard and grabbed the hair on his head. “Unbelievable!” he shouted. “I suppose next the king will be wanting my sheep and my girl, seeing as those are the only possessions I have left.”

“Do you own a girl?” said the soldier.

“I do,” said Uncle. “A worthless one, but still, she is mine.”

“Ah,” said the soldier, “that, I am afraid, is against the law, too; no human may own another in the Kingdom of Dor.”

“But I paid for her fair and square with a good laying hen and a handful of cigarettes and a blood-red tablecloth.”

“No matter,” said the soldier, “it is against the law to own another. Now, you will hand over to me, if you please, your spoons, your bowls, your kettle,

and

your girl. Or if you choose not to hand over these things, then you will come with me to be imprisoned in the castle dungeon. Which will it be?”

And that is how Miggery Sow came to be sitting in a wagon full of soup-related items, next to a soldier of the king.

“Do you have parents?” said the soldier. “I will return you to them.”

“Eh?”

“A ma?” shouted the soldier.

“Dead!” said Mig.

“Your pa?” shouted the soldier.

“I ain’t seen him since he sold me.”

“Right. I’ll take you to the castle then.”

“Gor,” said Mig, looking around the wagon in confusion. “You want me to paddle?”