The Sugar King of Havana (11 page)

Read The Sugar King of Havana Online

Authors: John Paul Rathbone

—RAFAEL ANTONIO CISNEROS,

La Danza de los Millones

La Danza de los Millones

L

obo’s childhood is also suffused with nostalgia, although of a different sort. If a lonely adult recalls early loneliness, an adventurer remembers moments of excitement, and Lobo was both a loner and an adventurer. The incidents that he remembered from his childhood show the same determination and picaresque impulsiveness of his later life. It was an explosive mix, as Heriberto foresaw.

Domina tus pasiones

, control your passions, he used to counsel his son. Because from an early age it was apparent that Lobo sought not only wealth but glory too.

obo’s childhood is also suffused with nostalgia, although of a different sort. If a lonely adult recalls early loneliness, an adventurer remembers moments of excitement, and Lobo was both a loner and an adventurer. The incidents that he remembered from his childhood show the same determination and picaresque impulsiveness of his later life. It was an explosive mix, as Heriberto foresaw.

Domina tus pasiones

, control your passions, he used to counsel his son. Because from an early age it was apparent that Lobo sought not only wealth but glory too.

As a young school boy, he went to Colegio de La Salle, which had just opened its doors five and a half blocks from his house. Founded by lay brothers in 1906, La Salle became one of Havana’s two great schools, the other being El Colegio de Belén, where Fidel Castro and his younger brother Raúl later received their Jesuit education. It was at La Salle that Lobo first realized his talent for speculation. Lobo’s classmates used to trade pencils during school breaks. When the games ended, Lobo usually found that he had collected the lot. He also showed an unusual interest in Napoleon at an early age, buying his first artifact from his father, an autograph. Heriberto asked for thirty pesos. Lobo, not yet a teenager, said he had only fifteen, so Heriberto, wanting to impart a useful lesson to his son, loaned him the remainder.

There was a tradition among wealthy Cubans that dated from colonial times of sending their children to be educated in the United States. And in 1910, just before his twelfth birthday, his parents dispatched Lobo to New York to board at Columbia Grammar in preparation for the more famous university fifteen blocks north. Bernabé’s sons also went to school in the United States; so did their sons—my grandfather went to Storm King in New York State. Lobo eventually sent his daughters north for a “proper education” at a young age too. From there, the usual route was on to an Ivy League college.

Lobo was being groomed for this path. In 1914, sixteen years old, precocious but “still wearing short pants,” he enrolled at Columbia University, one of the six youngest boys among the almost four hundred freshmen to join that year. He roomed at 738 West End Avenue, between Ninety-sixth and Ninety-seventh streets; mingled with the sons of other Cubans studying at Columbia, including his two future brothers-in-law; and attended lectures on mathematics, English literature, and philosophy. He continued the fencing lessons begun at preparatory school—at home, many Cubans still settled their differences with swords. In the evenings he went to Broadway shows, drawn by an early attraction to the stars of the stage, even if he could hardly see them from his cheap seats up in the highest balcony.

By his seventeenth birthday, Lobo looked set for the predictable education of a child of the Cuban well-to-do, studying law perhaps. But he was too restless and ambitious for that. “I decided to become a sugar expert,” Lobo remembered. “It was so intimately linked with what was going on.” Sugar prices had risen with the outbreak of World War I, and foreign investment had flooded the island chasing the profits to be made. While millions of men mobilized in Europe, Cubans planted sugarcane and reaped the riches. Sugar production doubled during the first decade of the century. It doubled again in the eight years to 1918 in a boom led by figures such as the merchant and planter Manuel Rionda.

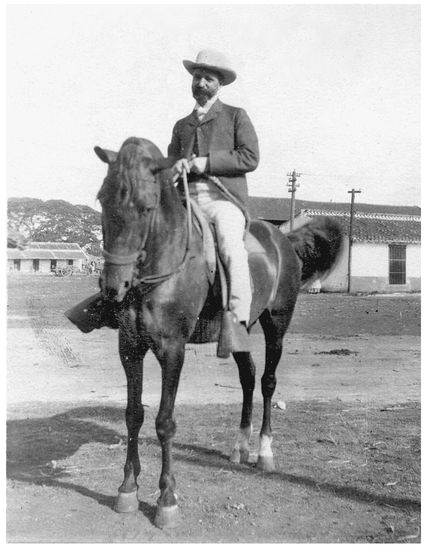

Manuel Rionda. Tuinucú, 1905.

A patrician Spaniard with dark hair, piercing eyes, and a Vandyke beard, Rionda bridged the worlds of Cuba and Wall Street with his old Spanish manners, and the scale of his operations at their peak was immense. He was copartner of Czarnikow Rionda, the powerful London-based trading house, and handled some 60 percent of Cuba’s sugar sales to refiners in the United States. His family had interests on the island that predated the wars of independence, and already owned three mills. In 1912, after raising the then huge amount of $50 million on Wall Street as president of the newly formed Cuba Cane Corporation, Rionda oversaw the purchase of seventeen more. He lived on a vast New Jersey estate at Río Vista overlooking the Hudson River, reputedly had oranges tied to the trees in his garden to remind him of his Spanish roots, and spent at least four months of every year in Cuba overseeing the

zafra

. He began the 1,300-mile migration every December in a private railroad car with his family and secretaries. The train left vaulted Pennsylvania Station for Key West, then they continued by boat to Havana, traveled east across Cuba by train again, the last leg completed when his carriage was unhitched from the Havana Special and hauled by one of Rionda’s own engines to the two-story, yellow

casa de vivienda

at his favorite mill, Tuinucú. From his bedroom suite on the first floor, Rionda could hear the steady beat of the mill grinding day and night next door, the shrieks from the whistle as shifts were changed, and the clanging of engine bells and the crash of cane as it was dumped from railroad cars and ox carts into the chutes. In its heyday, Cuba Cane was the largest sugar company in the world. Rionda called it his “baby.”

zafra

. He began the 1,300-mile migration every December in a private railroad car with his family and secretaries. The train left vaulted Pennsylvania Station for Key West, then they continued by boat to Havana, traveled east across Cuba by train again, the last leg completed when his carriage was unhitched from the Havana Special and hauled by one of Rionda’s own engines to the two-story, yellow

casa de vivienda

at his favorite mill, Tuinucú. From his bedroom suite on the first floor, Rionda could hear the steady beat of the mill grinding day and night next door, the shrieks from the whistle as shifts were changed, and the clanging of engine bells and the crash of cane as it was dumped from railroad cars and ox carts into the chutes. In its heyday, Cuba Cane was the largest sugar company in the world. Rionda called it his “baby.”

Lobo was spurred on by the fortunes that men like his father and Rionda made. He left Columbia after just one year, and in 1915 enrolled at the sugar engineering institute at Louisiana State University. Now a huge university of 28,000 students, LSU was then a small college campus on a deep and fast-moving stretch of the Mississippi River, about 140 miles upstream from New Orleans. Although far from the genteel Ivy League world, where most of his Cuban peers moved, Lobo felt immediately at home. New Orleans and Havana were entwined in the same Atlantic world, shared a common Caribbean culture, and had a common history; during the late eighteenth century, New Orleans had even answered to the Spanish garrison in Cuba. New Orleans and Havana also shared the same economy. On both sides of the Gulf of Mexico, tens of thousands of tons of sugarcane were planted, hoed, cut, lifted, and hauled every year. It was in Louisiana that Lobo first inhaled the acrid stench of burned cane, akin to roasted corn, and the sweet smell of molasses. “Once that perfume invades your nostrils, it permeates your whole body,” he liked to say. “You will never be able to get rid of it. Such was my case.”

Lobo lodged in rooms near the campus in Baton Rouge, dallied in New Orleans on weekends, staying in plush hotels like the Grunewald or the Monteleone when he could afford it, and spent his winters gaining work experience at nearby sugar refineries. Clad in rough overalls, he rolled exhausted into his dormitory bed every night after long days spent in the laboratory, monitoring the sugar produced in the giant milling and centrifuge sheds next door. Lobo sent home samples of sugar he had made for his father to inspect. Less innocently, he made hand copies of the refineries’ balance sheets and also mailed them to Heriberto, until he was caught and stopped.

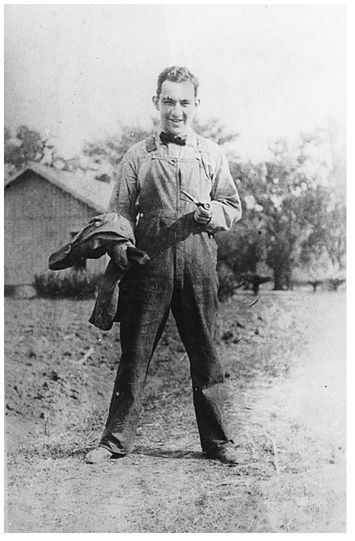

“El Veneno.” Louisiana, 1917.

Friends remember Lobo working hard, often late into the night, proudly encouraged by his father. “Your average mark in October was 85 per cent. In November it was 88 per cent,” Heriberto wrote halfway through Lobo’s second year. “If you keep on going at this rate, you will reach 100 per cent in May,” he teased. Yet there were also moments of Huckleberry Finn foolhardiness—Mark Twain’s book had been published only thirty years before.

One Easter, Lobo canoed with two friends to New Orleans. They paddled during the day, camping on the banks of the Mississippi at night, the canoe upturned and raised on blocks to make a rough shelter. They drifted lazily downstream, and made it to New Orleans two days later, having capsized several times in eddies. It was wartime and the Military Police, on the lookout for spies, arrested the bedraggled trio after they sneaked ashore through the wharves.

On another occasion Lobo swam the Mississippi, endangering his life and a friend’s, Charlie Coates, the son of the dean, and therefore his university education as well. It began as a student lark. They set off from the foot of Main Street in Baton Rouge, where the river was a mile wide and swept by at eight miles an hour. They swam safely to Port Allen on the other side, sliding downstream with the current, but struggled on their return. Coates lagged behind Lobo, the stronger swimmer. When they finally pulled themselves out of the water back at Baton Rouge, Coates’s mother was waiting on the shore, her eyes, Lobo never forgot, “full of fire over what she considered a virtual suicide jaunt.”

This was typical Lobo. Even as a young man, he focused on everything with a passionate and single-minded determination, be that studies, high jinks on the river, or women. Friends nicknamed him El Veneno, the poisonous one, for his charm and sibylline tongue. José Tiglao, a Philip-pine classmate at LSU and one of Lobo’s closest friends, remembered him as an “individualist, who does not spare himself any sacrifice to attain his objectives.” He also recalled Lobo’s golden touch. One Friday in their fourth year, Tiglao asked Lobo for a $5 loan to tide him over the weekend. Lobo, usually generous to a fault with friends, demurred. Instead he took Tiglao to the Hibernia Bank, where the Lobos banked, saying that he had a scheme which he hoped would bear fruit over the weekend. If he loaned his friend the money, Lobo explained, the interest he could charge would not match the profits he hoped to make.

There is a sharpness to this anecdote that can seem like unattractive tight-fistedness. Tiglao simply took it as an example of how Lobo viewed money. This depended on what end it was being used for; carousing with friends was one matter, business another. Clearly the scheme Lobo had in mind over that weekend worked, as did others like it, because when he graduated, Lobo repaid Heriberto his college fees. The show of independence angered his father, despite the lesson of the Napoleon autograph he had taught several years before. It was also central to Lobo’s belief that if he made it to the top, it would be from his own efforts. That is why he later avoided the corruption that enmeshed so much of Cuban business life. As Lobo saw it, turning to others for favors, let alone stealing, was a lesser man’s game. Making it on his own, whatever the cost, was not only a point of honor, it was a matter of pride.

Such pride brings costs. Acting the lone wolf also means suffering failure alone, as happened with one harebrained scheme that literally blew up in Lobo’s face. In 1916, the Allied troops were bogged down in the trenches in Europe, and the grenade was still a rudimentary weapon that often exploded in soldiers’ hands. Lobo imagined an improved model that would explode on contact with water when lobbed into the damp mud behind enemy lines. He dreamed that it would bring him the riches of Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, and help the Allies win the war.

Lobo worked on the device in the school’s chemistry labs during the evenings. Tiglao was dismissive, seeing it as “nothing more than a pipe dream, common to all students.” But Lobo worked on, ultimately to his own detriment, when the glass retort he used one night to mix chemicals had not properly dried. Tiglao was outside when he heard the explosion. He rushed into the building and found Lobo lying unconscious on the floor, broken laboratory apparatus strewn around him, his body peppered with shards of glass. An ambulance rushed Lobo to the Touro infirmary in New Orleans, where doctors painstakingly picked over his body and face. Lobo spent the next week with his eyelids clamped open, crying glass, the slivers floating out on his tears. Yet the only mark left by the accident was a shallow gouge on the end of his nose that looked like the faint shadow of a lunar sea on the face of the moon. In certain lights, as Lobo later liked to say, it resembled a question mark, a fitting scar for such a curious speculator.

Other books

Out of the Blue: A Pengram Mystery by Scarlett Castrilli

Hunting Lust (Orion the Hunter Part Three) by Chase, J.D.

Dev Conrad - 03 - Blindside by Ed Gorman

She's No Angel by Kira Sinclair

The Art of Adapting by Cassandra Dunn

The Devil Dances by K.H. Koehler

The Face of Another by Kobo Abé

The Last City by Nina D'Aleo

Dark Oil by Nora James

Frankentown by Vujovic, Aleksandar