The Story of the Romans (Yesterday's Classics) (27 page)

Baths of Caracalla

Although the new emperor was only fourteen years of age, he had already acted as high priest of the Syrian god Elagabalus, whose Greek name he had taken as his own. The beauty of Heliogabalus was remarkable, and he delighted in wearing magnificent robes, and in taking part in imposing ceremonies.

He is noted in history chiefly for his folly and his vices, and is said to have married and divorced six wives before he was eighteen years old. Elagabalus was made the principal god in Rome, and the emperor, we are told, offered human sacrifices to this idol in secret, and danced before it in public.

Either to make fun of the senators, or to satisfy a fancy of his mother and grandmother, Heliogabalus made a senate for women. His mother was made chief of the new assembly, and presided at every meeting with much pomp and gravity.

Even the Romans were shocked by the emperor's conduct, so the soldiers soon rose up against him. Bursting into the palace one day, they dragged Heliogabalus from the closet where he was hiding, killed him and his mother, and scornfully flung their bodies into the Tiber.

As soon as the soldiers had murdered the emperor, they proceeded to elect his cousin Alexander, who proved a great contrast to him in every way. Both of these young men belonged to the family of Severus; but, while Heliogabalus was ignorant and vicious, Alexander was both wise and good.

Unfortunately, however, he was not intended for the ruler of so restive a people as the Romans. Although he shone as a painter, sculptor, poet, mathematician, and musician, he had no military talents at all.

During his reign, the barbarians came pouring over the Rhine, and threatened to overrun all Gaul. Alexander marched against them in person, for he was no coward; but he was slain by his own soldiers during a mutiny. The trouble is said to have been caused by Maximinus, who became Alexander's successor, and hence the twenty-fifth emperor of Rome.

The Gigantic Emperor

T

HE

new emperor, Maximinus, was of peasant blood, and was a native of Thrace. He was of uncommon strength and size, and very ambitious indeed. As he found the occupation of herdsman too narrow for him, he entered the Roman army during the reign of Severus, and soon gained the emperor's attention by his feats of strength.

We are told that he was more than eight feet high, that his wife's bracelet served him as a thumb ring, and that he could easily draw a load which a team of oxen could not move. He could kill a horse with one blow of his fist, and it is said that he ate forty pounds of meat every day, and drank six gallons of wine.

A man who was so mighty an eater and so very tall and strong, was of course afraid of nothing; and you will not be surprised to hear that he was winner in all athletic games, and that he quickly won the respect of the Roman soldiers.

Maximinus was noted for his simplicity, discipline, and virtue as long as he was in the army; but he no sooner came to the throne than he became both cruel and wicked. He persecuted the Christians, who had already suffered five terrible persecutions under Roman emperors; and he spent the greater part of his time in camp. He waged many wars against the revolted barbarians, and we are told that he fought in person at the head of his army in every battle.

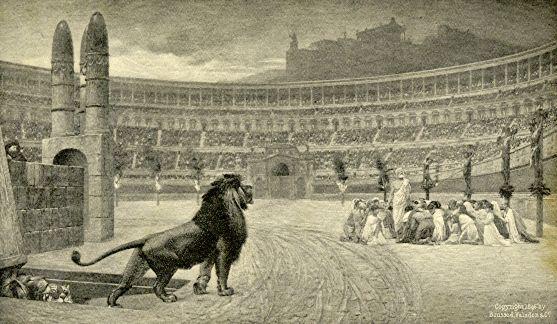

Christians in the Arena

The cruelty and tyranny of Maximinus soon caused much discontent, so his reign lasted only about three years. At the end of that time, his troops suddenly mutinied, and murdered him and his son while they were sleeping at noon in their tent. Their heads were then sent to Rome, where they were publicly burned on the Field of Mars, amid the cheers of the crowd.

Three emperors now followed one another on the throne in quick succession. All that need be said of them is that they died by violence. But the twenty-ninth emperor of Rome was named Philip, and during his reign the Romans celebrated the one thousandth anniversary of the founding of their beloved city. It had been customary to greet each hundredth anniversary by great rejoicings; and a public festival, known as the Secular Games, had been founded by Augustus.

Philip ordered that these games should be celebrated with even more pomp than usual, and had coins struck with his effigy on one side, and the Latin words meaning "for a new century" on the other. None but Roman citizens were allowed to take part in this festival, and the religious ceremonies, public processions, and general illuminations are said to have been very grand indeed.

The games were scarcely over, when Philip heard that a revolt had broken out among the Roman soldiers along the Danube River. To put an end to it as quickly as possible, he sent a Roman senator named Decius with orders to appease them.

Decius did his best to bring the soldiers back to obedience, but they were so excited that they would not listen to any of his speeches in favor of Philip. Instead of submitting they elected Decius emperor, much against his will, and forced him, under penalty of death, to lead them against Philip.

The army commanded by the unhappy Decius met Philip and defeated him. Philip was killed, and the new emperor marched on to Rome, where he soon began a fearful persecution of the Christians. Such was the severity used during the two years of this persecution, that the Romans fancied that all the Christians had been killed, and that their religion would never be heard of again.

Invasion of the Goths

D

URING

the reign of Decius, a new and terrible race of barbarians, called Goths, came sweeping down from the north. They were tall and fierce, and traveled with their wives and children, their flocks, and all they owned.

The Goths were divided into several large tribes: the Ostrogoths, or East Goths, the Visigoths, or West Goths, and the Gepidæ, or Laggards, so called because this tribe followed the others. All these barbarians spoke a rude Teutonic dialect, like the one from which the present German language has grown; and among the gods whom they worshiped was Odin.

The Goths met the Romans in several battles, and spreading always farther, ruined many towns, among others, Philippopolis, in Thrace, a city which had been founded by the father of Alexander the Great. Here they killed more than one hundred thousand people.

Decius marched against the Goths, hoping to punish them for this massacre; but he fell into an ambush, where he was killed with his son. His successor, Gallus, made a dishonorable peace with the barbarians, and allowed them to settle on the other side of the Danube.

Gallus and his general Æmilian, who succeeded him, were both slain by their own troops; and the next emperor was Valerian, who was the choice of the Roman legions in Rætia. This last named prince was both brave and virtuous. He arrived in Rome to find both Gallus and Aemilian dead, and took possession of the throne without dispute.

Although already a very old man, Valerian directed his son Gallienus to attend to the wars in Europe, while he went off to Asia to fight Sapor, King of Persia. This monarch had overrun much Roman territory, and had surprised the city of Antioch while the inhabitants were at the theater.

Valerian recovered Antioch from the enemy, but was finally defeated and taken prisoner. We are told that he was treated very harshly by Sapor, who used the emperor's neck as a mounting block whenever he wanted to get on his horse.

Some writers of history say that when Valerian died, the Persian king had him flayed. His skin was then dyed red, stuffed, and hung up in a temple, where Sapor insolently pointed it out to the Roman ambassadors, saying, "Behold your emperor!"

Zenobia, Queen of Palmyra

G

ALLIENUS

became sole ruler after Valerian's defeat; but he made no attempt to rescue or avenge his father, and thought of nothing but his pleasures. He was soon roused, however, by the news that the Franks had crossed the Rhine, and had settled in Gaul, which from them received its present name of France. Soon after, Gallienus heard that the Goths, sailing down the Danube, had come to the Black Sea, and were robbing all the cities on its coasts.

As Gallienus made no attempt to defend his people against the barbarians, the provinces fell into the hands of men who governed them without consulting the emperor at Rome. These men called themselves emperors, but they are known in history as the "Thirty Tyrants." One of them was Odenathus, Prince of Palmyra, in Syria, and he became very powerful indeed.

Another of these generals who had taken the title of emperor was intrenched in Milan. The real emperor, who was not a coward, fought bravely to capture this city; but he was killed here, and was succeeded by Claudius II., one of his generals.

The new Roman emperor was both brave and good. He began his reign by defeating the Goths, but before he could do much more for the good of his people, he fell ill and died, leaving the throne to Aurelian.

In the mean while, the kingdom of Palmyra had been gaining in power and extent. Odenathus was dead, but Zenobia, his wife, governed in the name of her young son. This queen was a beautiful and very able woman. She wished to rival Cleopatra in magnificence of attire and pomp, as well as in beauty.

After taking the title of Empress of the East, Zenobia tried to drive the Romans out of Asia. In full armor, she led her troops into battle, and conquered Egypt; and she entered into an alliance with the Persians.

Aurelian, having subdued the Goths, now led his legions against Zenobia. The Queen of Palmyra was defeated and her capital taken; and, though she attempted to flee, she fell into the hands of the Romans. Many of Zenobia's most faithful supporters were killed; and among them was her secretary, the celebrated writer, Longinus.

Palmyra itself was at first spared, but the inhabitants revolted soon after the Romans had left. Aurelian therefore retraced his steps, took the city for the second time, and, after killing nearly all the people, razed both houses and walls. To-day there is nothing but a few ruins to show where the proud city of Palmyra once stood; yet its wealth had been so great that even the Romans were dazzled by the amount of gold which they saw in Aurelian's triumph.

They also stared in wonder at Zenobia, the proud eastern queen, who was forced to walk in front of Aurelian's car. The unhappy woman could scarcely carry the weight of the priceless jewels with which she was decked for this occasion.

When the triumph was over, Zenobia was allowed to lived in peace and great comfort in a palace near Tibur; and here she brought up her children as if she had been only a Roman mother. Her daughters married Roman nobles, and one of her sons was given a small kingdom by the generous Aurelian.

About a year after the triumph in which Zenobia had figured, Aurelian was murdered; and for a short time no once dared accept the throne, for fear of dying a violent death. At last the senate chose a relative of the great Roman historian Tacitus; but he died of fever six months after his election, while he was on his way to fight the Persians.

A Prophecy Fulfilled

S

EVERAL

other emperors succeeded Tacitus at short intervals, and all died violent deaths after very brief reigns. Finally the army called Diocletian, an Illyrian soldier, to the throne.

It seems that a northern priestess had once foretold that Diocletian would gain the Roman throne when he had "killed the boar." All the people at this time were more or less superstitious, so Diocletian spent much time hunting. But, although he killed many boars, he was not for a long time named Emperor.

Now the two emperors who came before Diocletian were murdered by a burly soldier named Aper, a Latin word meaning "boar." Some of the legions then elected Diocletian to this office; and he, wishing to punish the murderer for his double crime, struck Aper down with his own hand.

His soldiers were familiar with the prophecy of the priestess, and they now cried that he would surely gain the throne, because he had killed the Boar. True enough, Diocletian's only rival was soon slain, and he was declared emperor by all the Romans.

Diocletian, however, found that the Roman Empire was too large and hard to govern for a single ruler. He therefore made his friend Maximian associate emperor. Then he said that Galerius and Constantius should be called Cæsars, and gave them also a portion of the empire to govern. These four Roman rulers had their capitals at Nicomedia, Milan, Sirmium, and Treves; and now a new epoch begins, with Rome no longer the central point of the government.

Diocletian remained the head and acknowledged leader and adviser of the other rulers. But his reign was troubled by invasions of the barbarians, a war in Persia, and a persecution of the Christians,—the worst and bloodiest that had yet been known.

A lover of solitude and simplicity, Diocletian soon tired of the imperial life. Therefore, when he felt that his strength no longer permitted him to serve the people, he withdrew to a quiet retreat in his native city of Salona, where he spent his last eight years in growing vegetables for his amusement.