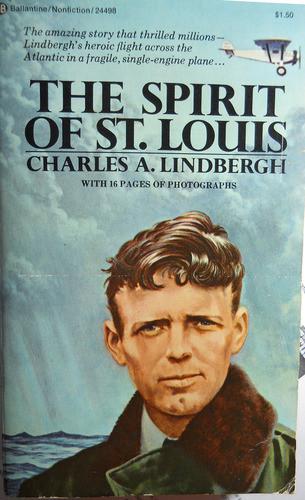

The Spirit of ST Louis

Read The Spirit of ST Louis Online

Authors: Charles A. Lindbergh

Tags: #Transportation, #Transatlantic Flights, #Adventurers & Explorers, #General, #United States, #Air Pilots, #Historical, #Biography & Autobiography, #Aviation, #Spirit of St. Louis (Airplane), #Biography, #History

home

The Spirit of Saint Louis

home

To

A. M. L.

home

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

In working over later drafts of the manuscript for The Spirit of St. Louis, I have used the facilities of several organizations and received assistance from many friends. I wish to express my deep appreciation to the following:

For reading part or all of the manuscript, and for citicism, suggestions, and assistance, which have been of tremendous value: Carl B. Allen; Dana W. Atchley; Betsy Barton; Jeanne A. Blitz; Harold M. Bixby; Kenneth Boedecker; Juno L. Butler; George T. Bye; Eva L. Christie; Michel Detroyat; Hope H. English; Margaret B. Evans; Paul W. Fisher; Judith S. Guild; Harlan A. Gurney; Elisabeth Habsburg; Donald A. Hall; J. G. E. Hopkins; Charles H. Land; Emory Scott Land; Kenneth M. Lane; Anne Morrow Lindbergh; Evangeline Lodge Land Lindbergh; Frank A. Lindbergh; Jon M. Lindbergh; Land M. Lindbergh; Lauren D. Lyman; Constance Morrow Morgan; Esther B. Mueller; Grace Lee Nute; Paul Palmer; Wesley Price; Dorothy E. Ross; Linda L. Seal; H. Robinson Shipherd; John Hall Wheelock.

For refreshing my memory and/or supplying information needed in various chapters: James T. Babb; Gregory J. Brandewiede; Paul E. Garber; Harry F. Guggenheim; John H. Towers; Willard R. Wolfinbarger.

For secretarial assistance: Dorothy M. Austin; Marta A. Brodie; Patricia Carey; Christine L. Gawne; Jeannette Greene; Gladys Leahey; Irene Leahey; Barbara Mansfield; Katharyne. Toner; Anne M. Wylie; Jean W. Wylie.

For research facilities and technical and historical data:

The Institute of the Aeronautical Sciences; The Minnesota Historical Society; The Missouri Historical Society; The National Aeronautic Association; The New York Public Library; The Smithsonian Institution; The Yale University Library.

For newspaper articles, extracts, and information: Aftonbladet, Stockholm; The Associated Press; Chicago Sunday Tribune; The Denver Post; Le Figaro, Paris; and HandelsZeitung, Berlin; International News Service; Los Angeles Times; The New York American; New York Herald Tribune; The New York Times; The New York World; La Prensa, Buenos Aires; St. Louis Globe-Democrat; San Diego Independent; San Diego Sun; San Diego Union; San Francisco Chronicle; The Sunday Star, Washington, D.C. The Times-Picayune, New Orleans; The United Press Associations.

For the use of lines from "The Builders" By Henry Wadsworth Longfellow: Houghton Mifflin & Co.

For hours which might otherwise have belonged to them: Jon, Land, Anne, Scott, and Reeve.

CHARLES A. LINDBERGH

MEMBERS OF

The Spirit of St. Louis

ORGANIZATION

HAROLD M. BIXBY

HARRY F. KNIGHT

HARRY H. KNIGHT

ALBERT BOND LAMBERT

J. D. WOOSTER LAMBERT

CHARLES A. LINDBERGH

E. LANSING RAY

FRANK H. ROBERTSON

WILLIAM B. ROBERTSON

EARL C. THOMPSON

IN GENERAL, this book is about flying, and an aviator's life, in the beginning third of the 20th century. In particular, it describes the planning and execution of the first nonstop airplane flight between the continents of America and Europe. It has been fourteen years in the writing. Started in the city of Paris, during the tense prewar winter of 1938, its manuscript was completed on the shore of Scotts Cove, off Long Island Sound, in the hardly more tranquil year of 1952.

The chapters that follow have been drafted and revised under conditions ranging from the uncertainty of a fighting squadron's tent in the jungles of New Guinea, to the stable family life of a Connecticut suburban home, and under such diverse daily influences as accompany noonday, midnight, and dawn. On top of a manuscript sheet I often marked down my location at the moment of writing or revising. Glancing through old drafts, I now pick out, more or less at random, the following geographical positions: aboard S.S. Aquitania, en route Cherbourg to New York; Army and Navy Club, Washington, D.C.; with the Marines on a Marshall atoll; in a bomber, returning from the North Magnetic Pole; General Partridge's residence at Nagoya, Japan; in a house trailer on the Florida Keys; on an air base in Arabia; parked on a roadside in the Italian Alps; camped in Germany's Taunus mountains; at the Carrels' island of St. Gildas.

Because the writing began more then eleven years after the last incident described took place, and because detailed records were not available at the time and later could not be transported everywhere the manuscript traveled, I have drawn heavily on memory for early drafts.

Searching memory might be compared to throwing the beam of a strong light, from your hilltop camp site, back over the road you traveled by day. Only a few of the objects you passed are clearly illuminated; countless others are hidden behind them, screened from the rays. There is bound to be some vagueness and distortion in the distance. But memory has advantages that compensate for its failings. By eliminating detail, it clarifies the picture as a whole. Like an artist's brush, it finds higher value in life's essence than in its photographic intricacy.

Records, on the other hand, illuminate the corners with which they are concerned, and surround your mind with their contemporary problems. They are relatively specialized, sometimes contradictory, and often incomplete. They restrict your perspective by bringing you too close to the area they cover. But they offer pay in precision for what they lack in breadth. I have rearranged and rewritten later manuscript drafts under the light of documents culled from attics, files, and libraries.

Throughout the following chapters I have digested conversations and press articles in order to avoid tedious detail. In telegrams I have used the originals where they were available, and approximated from memory where they were not. Since it is impossible to describe exactly the wanderings of the mind, I have placed flashbacks out of sequence to attain impressionistic truth. All incidents in this book are factual, and I have tried to put them into words with accuracy. The engine log and navigation log of the Spirit of St. Louis were stolen by some member of the crowd that overran fences and guards at Le Bourget. Therefore the log entries which form chapter heads in Part II have been filled in from performance curves and other records. The figures used are close to those marked down in flight, but there is certainly some variation.

When the Spirit of St. Louis flew to Paris, aviation was shouldering its way from the stage of invention onto the stage of usefulness. Enthusiasts still talked about "the conquest of the air." Rules for safety were sometimes just the reverse of today's. When a pilot encountered fog, he turned his eyes to the earth instead of to his dials, and the quality of

his senses was as important as that of his mind. The ability of an aircraft to make an emergency landing in a small pasture warranted a considerable reduction in its cruising speed; while the advantage of a cockpit forward, from the standpoint of vision, was more than offset by the advantage of a cockpit aft, from the standpoint of crash. But the monoplane had become a serious threat to the biplane's superiority. Instrument-flying techniques were being developed by the more progressive pilots. And promises of radio communication gave airmen cause for hope.

Along with most of my fellow fliers, I believed that aviation had a brilliant future. But my vision, extravagant as it seemed at the time, fell short of accomplishments now achieved with aircraft, by their pilots, engineers, and executives. Speeds, ranges, altitudes, powers, sizes, economies, and destructive capabilities today have shattered limiting factors of a quarter century ago. Science has transformed the frail craft of Le Bris, Lilienthal, and the Wright brothers into metal, and loaded them with cargoes varying from orchids to atomic bombs. Thousands of men, women, and children now cruise each day above the racing pilot's speed of 1927. Agencies all over the world sell tickets to cross the ocean at steamer-travel prices. Airlines have flown billions of passenger miles between fatalities. Engines have changed their horsepower ratings from hundreds into thousands. Military crews fly regularly above what the world's altitude record used to be.

Technically, we in aviation have met with miraculous success. We have accomplished our objectives, passed beyond them. We actually live, today, in our dreams of yesterday; and, living in those dreams, we dream again. Our visions of the future now embrace rocket missiles and supersonic flights. We speculate on traveling through space as we once discussed flying across oceans. But, unlike the early years of aviation, our dreams of tomorrow are disturbed by the realities of today. In this new, almost superhuman world, we find alarming imperfections. We have seen the aircraft, to which we devoted our lives, destroying the civilization that created them. We realize that the very efficiency of our machines threatens the character of the men who build and operate them.

Together with people outside the field of aviation, we find ourselves moving in a vicious circle, where the machine, which depended on modern man for its invention, has made modern man dependent on its constant improvement for his security—even for his life. We begin to wonder how rocket speeds and atomic powers will affect the naked body, mind, and spirit, which, in the last analysis, measure the true value of all human effort. We have come face to face with the essential problem of how to use' man's creations for the benefit of man himself. But this leads beyond the scope of my story, which ends on May 21, 1927, when we were still looking forward to the conquest of the air.

C.A.L.

CONTENTS

1. The St. Louis-Chicago Mail

2 New York

3 San Diego

4 Across the Continent

5 Roosevelt Field

6 New York to Paris

AFTERWORD

home

I

THE ST. LOUIS—CHICAGO MAIL

September, 1926

NIGHT ALREADY SHADOWS the eastern sky. To my left, low on the horizon, a thin line of cloud is drawing on its evening sheath of black. A moment ago, it was burning red and gold. I look down over the side of my cockpit at the farm lands of central Illinois. Wheat shocks are gone from the fields. Close, parallel lines of the seeder, across a harrowed strip, show while winter planting has begun. A threshing crew on the farm below is quitting work for the day. Several men look up and wave as my mail plane roars overhead. Trees and buildings and stacks of grain stand shadowless in the diffused light of evening. In a few minutes it will be dark, and I'm still south of Peoria.

How quickly the long days of summer passed, when it was daylight all the way to Chicago. It seems only a few weeks ago, that momentous afternoon in April, when we inaugurated the air-mail service. As chief, pilot of the line, the honor of making the first flight had been mine. There were photographs, city officials, and handshaking all along the route that day. For was it not a milestone in a city's history, this carrying of the mail by air? We pilots, mechanics, postal clerks, and business executives, at St. Louis, Springfield, Peoria, Chicago, all felt that we were taking part in an event which pointed the way toward a new and marvelous era.

But after the first day's heavy load, swollen with letters of enthusiasts and collectors, interest declined. Men's minds turned back to routine business; the air mail saves a few hours at most; it's seldom really worth the extra cost per letter. Week after week, we've carried the limp and nearly empty sacks back and forth with a regularity in which we take great pride. Whether the mail compartment contains ten letters or ten thousand is beside the point. We have faith in the future. Some day we know the sacks will fill.

We pilots of the mail have a tradition to establish. The commerce of the air depends on it. Men have already died for that tradition. Every division of the mail routes has its hallowed points of crash where some pilot on a stormy night, or lost and blinded by fog, laid down his life on the altar of his occupation. Every man who flies the mail senses that altar and, consciously or unconsciously, in his way worships before it, knowing that his own next flight may end in the sacrifice demanded.

Our contract calls for five round trips each week. It's our mission to land the St. Louis mail in Chicago in time to connect with planes coming in from California, Minnesota, Michigan, and Texas—a time calculated to put letters in New York City for the opening of the eastern business day.

Three of us carry on this service: Philip Love, Thomas Nelson, and I. We've established the best record of all the routes converging at Chicago, with over ninety-nine percent of our scheduled flights completed. Ploughing through storms, wedging our way beneath low clouds, paying almost no attention to weather forecasts, we've more than once landed our rebuilt army warplanes on Chicago's Maywood field when other lines canceled out, when older and perhaps wiser pilots ordered their cargo put on a train. During the long days of summer we seldom missed a flight. But now winter is creeping up on us. Nights are lengthening; skies are thickening with haze and storm. We're already landing by floodlight at Chicago. In a few more weeks it will be dark when we glide down onto that narrow strip of cow pasture called the Peoria air-mail field. Before the winter is past, even the meadow at Springfield will need lights. Today I'm over an hour late—engine trouble at St. Louis.

Lighting an airport is no great problem if you have money to pay for it. With revolving beacons, boundary markers, and floodlights, night flying isn't difficult. But our organization can't buy such luxuries. There's barely enough money to keep going from month to month.

The Robertson Aircraft Corporation is paid by the pounds of mail we carry, and often the sacks weigh more than the letters inside. Our operating expenses are incredibly low; but our revenue is lower still. The Corporation couldn't afford to buy new aircraft. All our planes and engines were purchased from Army salvage, and rebuilt in our shops at Lambert Field. We call them DHs, because the design originated with DeHaviland, in England. They are biplanes, with a single, twelve-cylinder, four-hundred-horsepower Liberty engine in the nose. They were built during the war for bombing and Observation purposes, and improved types were put on production In the United States. The military DH has two Cockpits. In our planes the mail compartment is where the front cockpit used to be, and we mail pilots fly from the position where the wartime observer sat.

We've been unable to buy full night-flying equipment for these planes, to say nothing of lights and beacons for the fields we land on. It was only last week that red and green navigation lights were installed on our DHs. Before that we carried nothing but one emergency flare and a pocket flashlight. When the dollars aren't there, you can't draw checks to pay for equipment. But it's bad economy, in the long run, to operate a mail route without proper lights. That has already cost us one plane. I lost a DH just over a week ago because I didn't have an extra flare, or wing lights, or a beacon to go back to.

I encountered fog, that night, on the northbound flight between Marseilles and Chicago. It was a solid bank, rolling In over the Illinois River valley. I turned back southwest, and tried to drop my single flare so I could land on one of the farm fields below; but when I pulled the release lever nothing happened. Since the top of the fog was less than a thousand feet high, I decided to climb over it and continue on my route in the hope of finding a clear spot around the air-mail field. Then, if I could get under the clouds, I could pick up the Chicago beacon, which had been installed at government expense.

Glowing patches of mist showed me where cities lay on the earth's surface. With these patches as guides, I had little trouble locating the outskirts of Chicago and the general area of Maywood. But a blanket of fog, about 800 feet thick, covered the field. Mechanics told me afterward that they played a searchlight upward and burned two barrels of gasoline on the ground in an effort to attract my attention. I saw no sign of their activities.

After circling for a half hour I headed west, hoping to pick up one of the beacons on the transcontinental route. They were fogged in too. By then I had discovered that the failure of my flare to drop was caused by slack in the release cable, and that the flare might still function if I pulled on the cable instead of on the release lever. I turned southwest, toward the edge of the fog, intending to follow my original plan of landing on some farmer's field by flarelight. At 8:20 my engine spit a few times and cut out almost completely. At first I thought the carburetor jets had clogged, because there should have been plenty of fuel in my main tank But I followed the emergency procedure of turning on the reserve. Then, since I was only 1500 feet high, I shoved the flashlight into my pocket and got ready to jump; but power surged into the engine again. Obviously nothing was wrong with the carburetor—the main tank had run dry. That left me with reserve fuel for only twenty minutes of flight—not enough time to reach the edge of the fog.

I decided to jump when the reserve tank ran dry, and I had started to climb for altitude when a light appeared on the ground—just a blink, but that meant a break in the fog. I circled down to 1200 feet and pulled out the flare-release cable. This time the flare functioned, but it showed only a solid layer of mist. I waited until the flare sank out of sight on its parachute, and began climbing again. Ahead, I saw the glow from a small city. I banked away, toward open country.

I was 5000 feet high when my engine cut the second time. I unbuckled my safety belt, dove over the right side of the fuselage, and after two or three seconds of fall pulled the rip cord. The parachute opened right away. I was playing my flashlight down toward the top of the fog bank when I was startled to hear the sound of an airplane in the distance. It was coming toward me. In a few seconds I saw my DH, dimly, less than a quarter mile away and about on a level with me. It was circling in my direction, left wing down. Since I thought it was completely out of gasoline, I had neglected to cut the switches before I jumped. When the nose dropped, due to the loss of the weight of my body in the tail, some additional fuel apparently drained forward into the carburetor, sending the plane off on a solo flight of its own.

My concern was out of proportion to the danger. In spite of the sky's tremendous space, it seemed crowded with traffic. I shoved my flashlight into my pocket and caught hold of the parachute risers so I could slip the canopy one way or the other in case the plane kept pointing toward me. But it was fully a hundred yards away when it passed, leaving me on the outside of its circle. The engine noise receded, and then increased until the DH appeared again, still at my elevation. The rate of descent of plane and parachute were approximately equal. I counted five spirals, each a little farther away than the last. Then I sank into the fog bank.

Knowing the ground to be less than a thousand feet below, I reached for the flashlight. It was gone. In my excitement when I saw the plane coming toward me, I hadn't pushed it far enough into my pocket. I held my feet together, guarded my face with my hands, and waited. I heard the DH pass once again. Then I saw the outline of the ground, braced myself for impact, and hit—in a cornfield. By the' time I got back on my feet, the chute had collapsed and was lying on top of the corn tassels. I rolled it up, tucked it under my arm, and started walking between two rows of corn. The stalks were higher than my head. The leaves crinkled as I brushed past them. I climbed over a fence, into a stubble field. There I found wagon tracks and followed them. Ground visibility was about a hundred yards.

The wagon tracks took me to a farmyard. First, the big barn loomed up in haze. Then a lighted window beyond it showed that someone was still up. I was heading for the house when I saw an automobile move slowly along the road and stop, playing its spotlight from one side to the other. I walked over to the car. Several people were in it.

"Did you hear that airplane?" one of them called out as I approached.

"I'm the pilot," I said.

"An airplane just dove into the ground," the man went on, paying no attention to my answer. "Must be right near here. God, it made a racket!" He kept searching with his spotlight, but the beam didn't show much in the haze.

"I'm the pilot," I said again. "I was flying it." My words got through that time. The spotlight stopped moving.

"You're the pilot? Good God, how – – – "

"I jumped with a parachute," I said, showing him the white bundle.

"You aren't hurt?"

"Not a bit. But I've got to find the wreck and get the mail sacks."

"It must be right near by. Get in and we'll drive along the road a piece. Good God, what went wrong? You must have had some experience! You're sure you aren't hurt?"

We spent a quarter hour searching, unsuccessfully. Then I accompanied the farmer to his house. My plane, he said, had flown over his roof only a few seconds before it struck the ground. I asked to use his telephone. The party line was jammed with voices, all talking about the airplane that had crashed. I broke in with the statement that I was the pilot, and asked the telephone operator to put in emergency calls for St. Louis and Chicago. Then I asked her if anyone had reported the exact location of the wreck. A number of people had heard the plane pass overhead just before it hit, she replied, but nothing more definite had come in.

I'd hardly hung up and turned away when the bell rang—three longs and a short.

"That's our signal," the farmer said.

My plane had been located, the operator told me, about two miles from the house I was in. We drove to the site of crash. The DH was wound up in a ball-shaped mass. It had narrowly missed a farmhouse, hooked one wing on a grain shock a quarter mile beyond, skidded along the ground for eighty yards, ripped through a fence, and come to rest on the edge of a cornfield. Splinters of wood and bits of torn fabric were strewn all around. The mail compartment was broken open and one sack had been thrown out; but the mail was undamaged—I took it to the nearest post office to be entrained.

The Illinois River angles in from the west. Lights are blinking on in the city of Peoria—long lines of them for streets; single spots for house and office windows. I glance at the watch on my instrument board-6:35. Good! I've made up ten minutes since leaving St. Louis. I nose down toward the flying field, letting the air-speed needle climb to 120 miles an hour. The green mail truck is at its usual place in the fence corner. The driver, standing by its side, lifts his arm in greeting as my plane approaches. And for this admiring audience of one, I dive down below the treetops and chandelle up around the field, climbing steeply until trembling wings warn me to level off. Then, engine throttled, I sideslip down to a landing, almost brushing through high branches on the leeward border.

The pasture is none too large for a De Haviland, even in daytime. We'll have to be doubly careful at night. If a pilot glides down a little fast, he'll overshoot. To make matters worse, a small gully spoils the eastern portion of the field for landing, so we often have to come in with a cross wind.

I taxi up to the mail truck, blast the tail around with the engine, and pull back my throttle until the propeller is just ticking over. The driver, in brown whipcord uniform and visored cap, comes up smiling with the mail sack draped over one arm. It's a registered sack, fastened at the top with a big brass padlock. Good! The weight of that lock is worth nearly two dollars to us, and there was registered mail from Springfield and St. Louis too. Those locks add an appreciable sum to our monthly revenue.

I toss the sack down onto aluminum-faced floor boards and pass out two equally empty sacks from St. Louis and Springfield. A few dozen letters in, a few dozen letters out, that's the Peoria air mail.

"No fuel today?"

"No, plenty of fuel," I answer. "I've had a good tail wind." It's a relief to both of us, for twenty minutes, of hard labor are required to roll a barrel of gasoline over from our cache in the fence corner, pump thirty or forty gallons into the DH's tank, and start the engine again. That is, it takes twenty minutes if the engine starts easily; an indefinite time if it doesn't.