The Snakehead: An Epic Tale of the Chinatown Underworld and the American Dream (2 page)

Read The Snakehead: An Epic Tale of the Chinatown Underworld and the American Dream Online

Authors: Patrick Radden Keefe

Tags: #Social Science, #General

Yang You Yi

,

Fujianese

Golden Venture

passenger and lead folding-paper artist in the prison in York, Pennsylvania

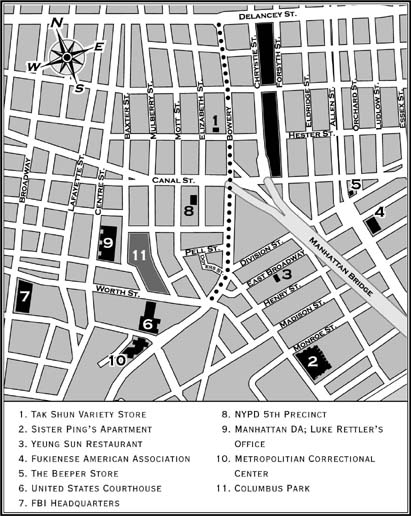

Chinatown

Chapter One

Pilgrims

THE SHIP

made land at last a hundred yards off the Rockaway Peninsula, a slender, skeletal finger of sand that forms a kind of barrier between the southern reaches of Brooklyn and Queens and the angry waters of the Atlantic. Dating back to the War of 1812, the people of New York erected battlements and positioned cannons along the beaches here, to defend against foreign invasion. Even before white settlers arrived, the local Canarsie Indians had identified in the eleven miles of dunes and grass something proprietary and exclusive. “Rockaway” derives from the Canarsie word

Reckouwacky

, which means “place of our own people.”

A single road runs down the center of the peninsula, past the Marine Parkway Bridge, which connects to the mainland, through the sleepy winterized bungalows of the Breezy Point Cooperative, right out to the western tip of Rockaway, where weekend anglers reel in stripers and blues. Looking south, past the beach at the Atlantic, you wouldn’t know you were on the southern fringe of one of the biggest cities in the world. But turn your head the other way, out across the bay side of the peninsula, and there’s Coney Island in the distance, the grotty old Cyclone tracing a garish profile above the boardwalk.

At a quarter to two on a moonless Sunday morning, June 6, 1993, a single police cruiser drove east along that central road, its headlights illuminating the dark asphalt. A large stretch of the peninsula is national

park land, and inside the car, a twenty-eight-year-old National Park Police officer named David Somma was doing a graveyard shift with his partner, Steve Divivier. At thirty, Divivier had been with the force for four years, but this was his first time on an overnight patrol.

It wasn’t typically an eventful task. The Breezy Point neighborhood west of the bridge was close-knit. The families were mostly Irish Americans who had been in the area for generations, working-class city cops and firefighters whose fathers and grandfathers had bought modest summer homes along the beach in the fifties and sixties and at some point paved over the sandy lots and winterized their weekend shacks. At 98.5 percent white, Breezy Point had the peculiar distinction of being the least ethnically diverse neighborhood in New York City. A night patrol of the beach might turn up the occasional keg party or bonfire, but serious crime along that stretch was unheard of. The Breezy Point police force was a volunteer auxiliary. The officers had so little use for their handcuffs that they had taken to oiling them to stave off rust.

Somma was behind the wheel, and he saw it first. An earlier rain shower had left the ocean swollen with fog. But out to his right, beyond the beach, the darkness was pierced by a single pinprick of faint green illumination: a mast light.

The officers pulled over, got out of the car, and scrambled to the top of the dunes separating the road from the beach. In the distance they beheld the ghostly silhouette of a ship, a tramp steamer, perhaps 150 feet long. The vessel was listing ever so slightly to its side. Somma ran back to the car and got on the radio, alerting the dispatcher that a large ship was dangerously close to shore. He and Divivier climbed the dune for another look.

Then, from out across the water, they heard the first screams.

Half stifled by the wind, the cries were borne to them across the beach. To Somma they sounded desperate, the kind of sound people make when they know they are about to die. He had a flashlight with him, and pointed it in the direction of the ship. The sea was rough, the

waves fierce and volatile. About 25 yards out, between the rolling swells, Somma saw four heads bobbing in the water. The officers turned and sprinted back to the car.

“We’ve got a large number of people in the water!” Somma shouted into the radio. Divivier had grabbed a life ring and was already running back to the beach. The officers charged into the water. It was cold—53 degrees—and the surf was violent, big swells breaking all around them and threatening to engulf the people in the distance. Guided by the wailing voices, Divivier and Somma strode out until they were waist-deep. As Divivier closed the distance to the four people, he hurled the life ring in their direction. But the wind and current carried it away. He reeled it in, walked deeper into the water, and cast the ring again. Again it failed to reach the people as they struggled in the swells.

Realizing that they couldn’t do the rescue from solid ground, Divivier and Somma plunged into the water and began swimming, enormous waves twisting their bodies and crashing over their heads. The drowning people writhed in the cold ocean. Eventually Divivier and Somma reached them and shouted over the percussive surf, telling them to take hold of the life ring. Then the officers turned around and dragged the shipwrecked strangers back to shore. There the four collapsed, panting, on the sand. They were Asian men, the officers saw, diminutive and cadaverously thin. When Somma spoke to them, they didn’t appear to understand. They just looked up, with terror in their eyes, and pointed in the direction of the ship.

From the ocean, the officers heard more screams.

S

omma’s first radio call to the Park Service Police dispatcher had gone out at 1:46 A.M. There was a Coast Guard station just across the peninsula from the beach, at the Rockaway end of the Marine Parkway Bridge. Charlie Wells, a tall, ruddy, nineteen-year-old seaman apprentice, was on radio duty from midnight to four in the morning. Wells, the

son of an Emergency Medical Services captain, had grown up in White-stone, Queens. He lived in the barracks; he’d been with the Coast Guard less than a year.

“A fishing boat sank off Reis Park,” a dispatcher’s voice said, crackling through the radio. “There’s forty people in the water!”

Wells ran out of the barracks, started his truck, and drove a few hundred yards south down the access road in the direction of the ocean side beach. He pulled over in a clearing and ran up onto the beach, where he was startled by the sight of the ship in the distance. He mouthed a quiet

Wow

.

On the beach in front of him, it looked like some madcap game of capture the flag was under way. A dozen or so dark, wiry figures, some of them in ragged business suits, others in just their underwear, were running in every direction, and a number of burly police officers were giving chase. Three off-duty Park Service officers had joined Somma and Divivier and were scrambling after the Asian men who had managed to swim to shore.

“Help!” one of the officers shouted, spotting Wells.

Wells took off after one of the men, gained on him easily, and rugby-tackled him. He was much smaller than Wells, skinny, and soaked through. Wells held the man down and looked up to see more people emerging from the surf. It was a primordial scene—an outtake from a zombie movie—as hordes of men and women, gaunt and hollow-cheeked, walked out of the sea. Some collapsed, exhausted, on the sand. Others dashed immediately into the dunes, trying to evade the cops. Still more thrashed and bobbed and screamed in the crashing waves. Wells could just make out the outline of the ship in the darkness. There was movement on the deck, some sort of commotion. People were jumping overboard.

“We need a Coast Guard boat!” one of the officers shouted at Wells. “And a helicopter!”

Wells ran back to the van and radioed his station. “I need more

help,” he said. “There’s a two-hundred-foot tanker that ran aground right off the beach, and these guys are jumping right into the water.”

The tide was coming in, and a strong westerly crosscurrent was pulling the people in the water down along the shoreline. The officers ventured into the water again and again. They plucked people from the shallows and dragged them onto the shore. The survivors were terrified, eyes wild, teeth chattering, bellies grossly distended from gulping saltwater. They looked half dead. They were all Asian, and almost all men, but there were a few women among them, and a few children. They flung their arms around the officers in a tight clench, digging their fingers so deep that in the coming days the men would find discolored gouge marks on the skin of their shoulders and backs.

The night was still so dark that it was hard to locate the Asians in the water. The men relied on their flashlights, the narrow beams roving the waves in search of flailing arms or the whites of eyes. But the flashlights began to deteriorate from exposure to the saltwater, and when the lights failed, the rescuers had to wade out into the darkness and just listen for the screams. “We entered the water guided only by the sound of a human voice,” one of the officers later wrote in an incident report. “When we were lucky, we could then use our flashlights to locate a person … When we weren’t lucky, the voices just stopped.” The rescue workers pulled dozens of people to shore. Every time they thought they had cleared the water, another pocket of screams would pick up, and they would head back in.

Those who were too tired to walk or move the officers carried, jack-knifed over their shoulders, and deposited on higher ground. There they collapsed, vomiting saltwater, their bodies shaking, their faces slightly purple from exposure. The officers tried massaging their legs and arms to improve circulation. Some were hysterical, sobbing and pointing out at the ship. Others seemed delusional and rolled around covering themselves with fistfuls of sand, whether to insulate their frozen bodies or hide from the officers was unclear. Some were more collected—they

were strong swimmers, or they had caught a generous current. They walked up out of the water, stripped off their wet clothes, produced a set of dry clothes from a plastic bag tied around an ankle, and changed right there on the beach. Some of them then sat among the growing number of survivors on the sand, waiting to see what would become of them. Others simply walked off over the dunes and disappeared into the dark suburban stillness of Breezy Point.

A

cross New York and New Jersey, telephones were beginning to ring. Cops and firefighters, rescue workers and EMTs, reached for pagers buzzing on darkened bedside tables and rolled out of bed. When a disaster occurs, most of us are hardwired to run in the opposite direction, to stop and gawk only when we’ve put some distance between ourselves and any immediate risk. But there’s a particular breed of professional who always runs toward the disaster, even as the rest of us run away. As word spread among the first responders in New York and New Jersey that a ship full of what appeared to be illegal aliens who couldn’t swim had run aground in the Atlantic, a massive rescue got under way. It would prove to be one of the biggest, and most unusual, rescue operations in New York history—“like a plane crash on the high seas,” one of the rescue workers said.

A heavyset Coast Guard pilot named Bill Mundy got the call as he was finishing a maintenance run in his helicopter and had just touched down at the Coast Guard’s hangar at Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn, across the bridge from Rockaway. The propeller was still spinning, and Mundy summoned his copilot and two rescue divers, climbed back aboard, and lifted off, ascending 50 feet into the air. The fog was clearing, and past the bridge, beyond the dark strip of roofs and trees on Rockaway, they could see the ship, just a few miles away as the crow flies, protruding from the slate-dark sea. The helicopter tore through the sky, and below they could see the bleeding strobe of emergency vehicles

—ambulances, squad cars, a convoy of fire trucks hurtling over the bridge toward the beach.

The helicopter reached the scene in minutes, and Mundy saw people on the beach below and people in the ocean. The chopper’s spotlight searched the scene, a pool of white light skimming across the black water and spilling onto the dark shapes aboard the vessel. The ship was called the

Golden Venture

, its name stenciled in block letters on the salt-streaked bow. Its green paint was scarred by rust along the waterline. Two rope ladders had been flung over the side, and people were climbing halfway down the ladders and jumping into the water.

Mundy couldn’t believe it. He’d rescued a lot of people from the water, and what they always feared most was the unknown aspect of the sea—that voracious, limitless, consuming darkness of the ocean. But here these people were in the middle of the night, in a strange place, 25 feet above the water, and they were just pouring over the side of the ship like lemmings.

This is very high on the “I’m gonna die” list

, Mundy thought. They were lining the decks, emerging through hatches from the bowels of the ship. They were moving as people in shock do, their bodies erratic, herky-jerky as they dashed back and forth in a lunatic frenzy, and cannonballed over the side.

Mundy hovered down, the chopper getting closer to the ship, training the bright searchlight, unsure what to focus on. The people on board looked up, alarmed, and dashed to and fro. “DO NOT JUMP,” Mundy’s copilot said over the loudspeaker. “STAY ON BOARD.” But the whir of the propeller drowned him out. And even if they could hear, Mundy realized, these people weren’t American; there was no telling what language they spoke. The helicopter descended closer still and Mundy and his colleagues tried signaling with their hands, using palm-extended gestures of restraint, hoping the people on deck would see them. But the rotor wash was strong enough to knock a man down, and as they came in close, the people just panicked, scattering to the other end of the deck.