The Slightly Bruised Glory of Cedar B. Hartley (17 page)

Barnaby says, âYeah, but that's Cedar. She just feels strongly about anything. She feels strongly about sultanas in the muesli. She's like me.'

I get a feeling there's a bit of a romantic moment going on now. I can tell by the tone in Barnaby's voice, which has gone tender-hearted. And there's almost the quiet, soundless sounds of blushing and touching and eyelashes, and I start feeling squeamish and like I'm about to suffocate in the stench of sentiment, until Ada sighs and starts fiddling around in the tape box for music. She puts on some mournful lady with a piano, and the conversation turns to music. After a while, they pull in for petrol.

I'm actually busting for a wee myself, and I'm really straining my otherwise feeble ability to be still and quiet. So, while they are both out of the car, I push off the blanket, have a stretch, let out a few cheery sounds and peek out the window. The Billabong One Stop. A middle-of-nowhere truck stop. A weird skinny guy with dark glasses and a footy vest walks by, twisting an ice-cream wrapper. He doesn't see me but I see him. I also see that we're in the country now, so I happily hunker down again because I'm pleased I'll be able to reveal myself soon.

After we take off again, Barnaby changes the music and puts on âG Love and Special Sauce'. One of my favourites. Then he says, âHey, Ada, I want to send Cedar a postcard. It's a list. Can you write something down for me? The title is: A List of Creek Names Between Melbourne and Albury. So far, Two Mile Creek, Faithful Creek,Turnip Creek, Black Dog Creek and Pelican Floodway.'

âPelican Floodway? Is that a creek?'

âI don't know, but she'll like it.'

A little while later, he says, âYou know, the thing about Cedar is that some of the time she fixes her heart so strongly on something she doesn't really see it for what it is. You know what I mean? She's going to think this circus in Albury is the be-all and end-all. And I just don't want her getting too disappointed if it doesn't turn out to be what she thinks it will be.'

Ada doesn't reply. But Barnaby seems to be in the mood for speech-making, anyway. What would he know? He's never even done a proper cartwheel in his life.

âI mean, I think the glamour of it is exciting for her. She's got this idea that it's a “real” circus, whereas the one she's in now with her friends isn't.'

The glamour of it? As if I give a stuff about that. Only I do like the idea of touring the world â who wouldn't?

Ada says, âStill, she has to make her own decisions about what's best for her.' (Well said, Ada, you're a champ.)

Barnaby says, âExactly. In fact if I was her I would've just stowed away in the car and come along to see.'

Ada says, giggling, âSo you wouldn't have been mad with her if she had stowed away?'

Barnaby says, âNope. In fact, I just accidentally bought a double choc Magnum ice-cream, in case she had, but since she hasn't I may as well eat it myself.'

At this point I throw off the blanket and sit up with a big snort.

âOkay, okay, hand it over then, 'cause I'm starving.'

Without even looking, Barnaby passes it over his shoulder and says to Ada, âSo, looks like we've got ourselves a real live stowaway.'

Ada turns around and winks, and I mouth the word âthanks'.

âLooks like it,' I say, and I'm so relieved that Barnaby's not chucking me out that I settle back and start singing along to âG Love' as loudly as I can. I watch the fields and the sky with the glorious, glowing feeling of my adventure really being under way.

Before we get there, Barnaby says, âSo, little champ, where were you planning on staying?'

I hadn't actually planned beyond Step 5, of course. In some ways I hadn't dared believe I'd actually get beyond it. So I sit there with my mouth open like a big dumbo.

âBecause at the Termo, where we're playing, they've got a room for us. We could probably smuggle you in there.'

I know where I want to stay and where I'd imagined I would stay, and it wasn't crammed in between Barnaby and Ada in some grungy hotel room.

âNo, I'll stay at Kite's,' I say, âonly he isn't exactly expecting me. Well, he is, but he isn't expecting me exactly now. Actually, he doesn't know when to expect me because, see, I wasn't sure I'd, you know, make it or not.'

Truth was, Kite and I had never discussed accommodation, but I wasn't going to let on quite how disarrayed my plan actually was. At least I had the address and I was sure that if I just showed up they'd let me stay. That's what folk do in the country.

The problem is that when we do show up, there's no one home. The house is a nice big yellow wood house with a huge oak tree, just like ours.

âLook,' I say. âJust leave me here and I'll wait. They can't be long.'

âWe can't just leave you. Imagine. I'm going to have to call Mum and let her know you're with us. I'm not saying we just left you on a doorstep.'

After a lot of arguing, I persuade Barnaby to leave me on the doorstep. The plan is: if I don't call him in an hour to let him know I'm safe, he'll come back and get me.

âGive me two hours. It's light. I've got a good book. Look.' I flash

The Road Less Travelled

at them.

Barnaby says, âYou've got 'till 5.30.'

I want to be alone when I see Kite. I don't want big brother hanging around. I want to look like a brave traveller, a fearless risk-taker But also I want to look like I'm completely alone in the world so that he feels obliged to offer me lodgings. Let's say, brave â slightly ravaged from effect of long journey â orphan, in need of loving care, waiting on the doorstep, is the feel I'm going for. So it simply won't suit the story if Barnaby and Ada are with me. Not at all.

I'm relieved when they go, even though I've changed my opinion of Ada. In fact I have myself a little think about her. Aunt Squeezy says Buddhists try not to have opinions, because it can make you righteous, which means you always think you're right and you don't listen to other possibilities like, for instance, âyou're wrong'. But sometimes you don't realise you develop certain opinions until life does something to show you and your opinions up.

I had an opinion that Ada was kind of snotty and superior, but now I think she's just quiet around other people. Maybe she's even shy. Whatever she is, she's got an understanding heart because not only did she not blow my cover (not until the Billabong One Stop, anyway), I reckon she also tried to make Barnaby understand where I'm coming from.

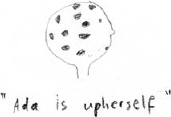

So, I have a good think about opinions. I get a pile of stones and I put them on the front verandah, and then I get a bit of chalk and I draw a big head shape around the stones, like this:

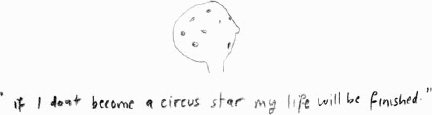

The head represents my head, and the stones represent all the opinions I have in my head, making my head heavy and impenetrable. And then I try to work out what these opinions are, because once I know them I'm allowed to take the rocks out of my head and throw them away. The idea is to get my head to look like this:

The first opinion I pull out is this:

That one's easy because I've already kind of dislodged it. But I needed an encouraging take-off. The next one is harder:

I put the stone on the borderline because I can't really be convinced I've let go of that opinion.

So then I try switching from people to other stuff like:

Strangely, it's just as I am catapulting that opinion out of my head that two brown, blistered feet in thongs enter the picture: