The Slightly Bruised Glory of Cedar B. Hartley (16 page)

âThe drawing's wrong,' she says.

âIt's very sad,' I say. âI think it's a great drawing.'

âIt's meant to be Mohammed,' she says. âNot exactly him, but you know, something of him.'

Mohammed is the Afghan boy who never joins in; the one who just appears in the doorway like a small, dark ghost. I realise that it isn't exactly sadness that's in the face, but an absence, a sense that something isn't there.

âIt looks as if he's haunted,' I say, and I wonder if he remembers what he has lost.

âYeah. He is. I wish he could join in but I think he's shy. I think he's proud too. He's afraid he might make a fool of himself.'

I look at Caramella with her soft, round face studying her drawing, and I can see she has really been thinking about Mohammed, and she's concerned. I think even in some way she might feel she understands him. I remember how shy she was when I first dragged her along to training, how she glued herself to the wall pulling her T-shirt down and how, bit by bit, she became more willing to have a try.

âAfter all,' she says, looking up at me as she stretches her legs and puts the drawing down, âthat's the point, isn't it? I mean, the whole reason we're teaching circus there is to teach them something that makes them enjoy themselves.'

âYeah. For sure. That's the point. But also it's good for anyone to feel they're learning something. You keep trying and you get better at it. That's why I just tried to hit a balance on a skateboard.'

âAnd still you haven't given up?'

âNo way.'

Caramella laughs.

âAh, Cedar, that's when you're great. That's when you're at your best. When you don't give up.'

We both look at each other. I'm sitting on the back of the couch. There's a tiny serious moment when I have a feeling that she's just said something meaningful, something that reaches further than skateboard hand balances. I know it has something to do with me giving up on the circus, and then not giving up on the circus. Sometimes your own importance wells up way beyond your self and submerges the real things, the things that count. I guess meeting Inisiya had reminded me that the circus didn't have to be about me, it could be about something else, about the things Caramella was talking about. I feel very warm right then, in that serious moment, and without really knowing exactly why I reach down and give Caramella a big hug. And then I drag her outside to spot me while I keep trying to hit that balance. I'm like a dog with a bone when I really want to learn a new trick.

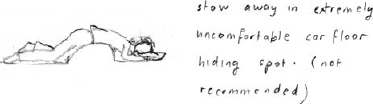

So, it's the night before my great adventure and I'm secretly packing my things. I'm trying to take as little as possible, since I need to be slim and streamlined enough to slither into the back of a Holden without looking like a small, quivering human bump.

Let me tell you, it's very hard for me to take only a few things as I tend to imagine situations in which I might need a tennis racquet or a candle or a pineapple, or Barnaby's lava lamp, or even a very glamorous dressâ¦Just imagine I'm living with Kite and Ruben and one night a visitor from Argentina arrives and decides to teach us all how to tango. Well, a long dress would be essential and a lava lamp would very much add to the atmosphere.

But since I don't have that kind of a dress or a tennis racquet, and Barnaby would kill me if I took his lava lamp, which is lilac, I managed to cut it all down to two green apples, trackie pants and singlet, torch, bathers, nightie, a book called

The Road Less Travelled

, which Aunt Squeezy lent me, my diary, the skateboard and of course Harold Barton's letter (still burning, burning, burning).

When I go to bed the night before Albury, it feels a lot like the way the night before Christmas used to feel when I was little. I'm so excited it takes me a long, long bout of thinking and dreaming before I fall off to sleep. And by the time I get up the next morning, I'm beginning to have fears instead.

What if Barnaby and Ada discover me early and kick me out of the car?

How will I cope with the disappointment, the humiliation?

What if I make an absolute fool of myself at the audition?

What if I really do get into the circus and I have to move to Albury without Mum?

And what if Stinky can't come and live with me?

I start to feel very lonely. I wish someone was going with me. I wish even Caramella could pop over and say, âgoodbye, good luck.' If only I could take Stinky, the little hairy guy, with me. I try to distract myself from these thoughts by rolling out of bed just as if it was a normal day. But as soon as Stinky hears I'm up he noses his way into my room for a pat, and I pull him onto my lap.

Sometimes I think I love Stinky too much. I mean it makes me scared how much I love that dog. Once you love someone, even a dog someone, even a cockatoo, you start thinking that life would be unbearable without them. Maybe not everyone thinks that, but I do, because I can't stop my imagination running away, running like an untamed horse, windswept and blustery, through the forests, sometimes going to wildly sad places and sometimes to wildly great places, but there's no doubt it's got the taste for roaming and if it comes across an idea that maybe one day Stinky might not be here it can be so utterly convincing that I start feeling unbearably sad. And I mean unbearably. But then there's not much you can do because you can't subtract your love to make it less. You can't close it up or tie it down. Once it's out, it's out, and you can't get it back in. Imagine if everyone could measure out the exact amount of love they were willing to gamble. But even if I could do that I reckon I'd still be a gambling man, I mean a high roller, like my Aunt Squeezy. She's always giving too much love, especially to Italian cads. Can you do love too much? I know there's a lot of things that you shouldn't do too much, like telling lies, watching telly (especially up close â it makes your eyes square), showing off, eating green apples off Caramella's tree (gives you the runs), but I never heard anyone say, âNow now, don't you go and love that person or that dog or you'll get the runs.'

Oh, life is very, very big.

I go eat breakfast and I act as normal as possible. Mum, as usual, is racing out the door with a piece of toast in one hand, keys in the other. She kisses me goodbye, says, âHey, vegie lasagne for dinner tonight,' because she knows it's my favourite.

I say,âMmmm-mmm, great,' just as if I'm really excited about that.

A minute after she has left, she comes back, bursting in with a frown and unwinding a car key from her keys and whacking it on the kitchen table.

âCedie, tell Barn when he gets up that this is the only car key I've got so he can't lose it. And also could you remind him to check the oil and water and pump up the tyres and, oh God, he's so vague â he's likely to blow the head gasket.'

âMum, you'll blow your own head gasket if you don't stop worrying,' I say.

She grins again and rushes out with a wave, leaving me alone with the smell of toast and a small, sweet, fond feeling for her. She's a good mum, I think to myself, just as all soldiers think when they lean out the train window and wave goodbye to their weeping mothers on the platform. I don't dwell on this for too long; instead, I begin to make myself scrambled eggs on toast, not my usual breakfast but one that most brave journeymen must eat before a big day. As I scramble the eggs I go over the plan:

1. Make like I'm going off to school, just as always (have already sussed out estimated time of departure is midday).

2. Instead, go down to creek and practise pole positions and audition routines.

3. At about eleven-thirty, sneak back and wedge myself and my pack on car floor behind front car seats, cover with picnic rug.

4. Lie very still and begin to pray.

5. After car has left, wait at least one and a half hours so that it's too far out of town to be sent back, then reveal myself directly. Make a very good joke so that Barnaby will not be too mad.

But it is somewhere between step three and four that the story doesn't quite go according to plan. This is what happens: I've managed to wriggle down and cover myself up. Luckily, the back seat has already been pushed down and this almost covers me. Barnaby and Ada are packing the car, shoving guitars and amps in the back. Aunt Squeezy is helping them. I'm hardly breathing. The car door near my head opens and someone is pushing things around. Aunt Squeezy is saying, âHave you got water? What about taking some fruit?' And then suddenly the blanket is ripped off my head and I'm staring at Ada and she's staring at me. She's frozen, half bent down with a pillow under her arm, and so am I, eyes cranked up towards her imploringly.

Barnaby is calling from the boot, âHey, Ada, did you put the doona in?'

She doesn't answer him. She opens her eyes wider as if to make sure she really is seeing what she thinks she's seeing, and I put my finger to my mouth.

âAdie?' says Barnaby.

I feel my face contort in alarm, which she must register as well, because suddenly she snaps out of our frozen exchange and she stands up.

âYeah, I put it in,' she says. âI'm just stuffing the pillows behind the seat.' She bends down again, looks at me in a slightly confused way, as if maybe I'm something she can't quite recognise. Then she quickly stuffs the pillow under my head and covers me up. A few minutes later, we're on the road.

I can hardly believe it. I can't believe Ada didn't blow my cover. I lie there picturing myself in years to come, telling the story while wearing something cavalier like a slanted felt hat. I'd be saying, âI can't believe the dame didn't blow my cover. Man oh man, was I one lucky son of a bitch.' But, to tell you the truth, I don't actually dig that expression âson of a bitch'. It's like making out that dogs and mothers are the ones to blame. So I wouldn't say it exactly that way.

I'm very uncomfortable, and doubting that I can keep still for the planned one and half hours. It's bumpier and smellier and stuffier than I ever imagined. Luckily, it's not long before Ada strikes up an intriguing conversation with Barnaby.

âHasn't Cedar got a boyfriend at Albury?'

Barnaby laughs. âYeah, kind of. I don't know if it's got to that yet, but there's something going on. He's in some circus up there.'

Ada says, âI guess she would have liked to have come with us then.'

Barnaby doesn't answer for a minute and I feel a squirm coming on. Then he sighs.

âYeah, probably. Well, before Kite left he told me there'd be auditions towards the end of the year, because I told him that we might be passing through Albury on tour. He said not to tell Cedar straight away because he'd have to find out first whether she could audition. But if she could, we planned that I could bring her up.'

Ada says, âSo? What happened?' I'm really beginning to like Ada. Thank God for Ada.

Barnaby says,âWell, turns out you have to live in Albury if you want to join that circus, and Mum can't possibly move there. Mum said she'd spoken to Cedar about it. There'd be no point in her doing the audition if she can't join.'

âOh,' says Ada, and then there's quiet, just the sound of wind through the windows. I imagine that outside there are fields of yellowed grass with black cows lying down.

Then Ada says, âCan't she live with some other family there, like a boarder?'

And I think, what a great idea. How come I didn't think of that?

Barnaby says, âI don't know. I just think it would kill Mum, you know, if Cedar left home now. Mum's lost enough already. Anyway, Mum reckons Cedar wants to go more for the boy than the circus, and those kind of teenage crushes, they pass. She'll meet someone else and forget all about Kite and the circus.'

Forget all about Kite and the circus? Like hell I will. I can hardly stop myself from sitting bolt upright and putting him straight.

Luckily, Ada says, âDo you think? I mean do

you

think so? She seems pretty determined to me. I reckon she seems to feel quite strongly.'